Thermal Processing for EV Components

The advent and increasing adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) has brought a wave of change to the automotive supply chain, including the heat treating industry. While the internal combustion engine (ICE) and all its related components may one day become a thing of the past, there are several key areas of every vehicle that aren’t going anywhere fast. In this Technical Tuesday article, Rob Simons, metallurgical engineering manager at Paulo, discusses the difference between EV and ICE vehicles and the latest heat treating trends to be aware of.

This informative piece was first released in Heat Treat Today’s August 2024 Automotive print edition.

ICE vs. EV Technology

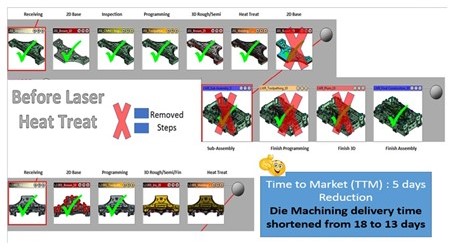

The most apparent difference between EVs and ICE vehicles is that, with EVs, fuel and internal combustion engines are no longer needed. The two vehicle types rely on different sets of key components, and when it comes to making the cars run, EVs use fewer parts that require heat treatment.

Without ICE systems, EVs require fewer fasteners, shafts, gears, and rods — all parts that are typically heat treated. But that doesn’t mean heat treatment is less critical for EVs. In fact, certain parts require additional attention on EVs when compared to ICE vehicles, and many safety-critical parts remain the same across both categories. Let’s begin our discussion with the differences in braking systems between the two technologies and what that means for heat treatment.

Latest Trends in Disc Brake Rotors

How EV Brake Systems Work

There’s no question that electric power innovations have completely revolutionized the way vehicles (and the automotive industry) operate. The regenerative braking system is just one aspect of this. Instead of relying on the conventional hydraulic system every time you press the brakes (which uses friction to decelerate), manufacturers have found a way to use the vehicle’s kinetic energy to put the electric motor into reverse, slowing down the vehicle and returning energy to the battery.

Although regenerative braking is more efficient, hydraulic braking still has one key advantage: stopping power. EVs today are equipped with conventional braking mechanisms for emergency purposes.

The Rust Conundrum

To address recurring rotor corrosion, heat treaters introduced ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC). FNC is a thermal process traditionally used for case hardening, and for brake rotors, it’s used to achieve corrosion resistance.

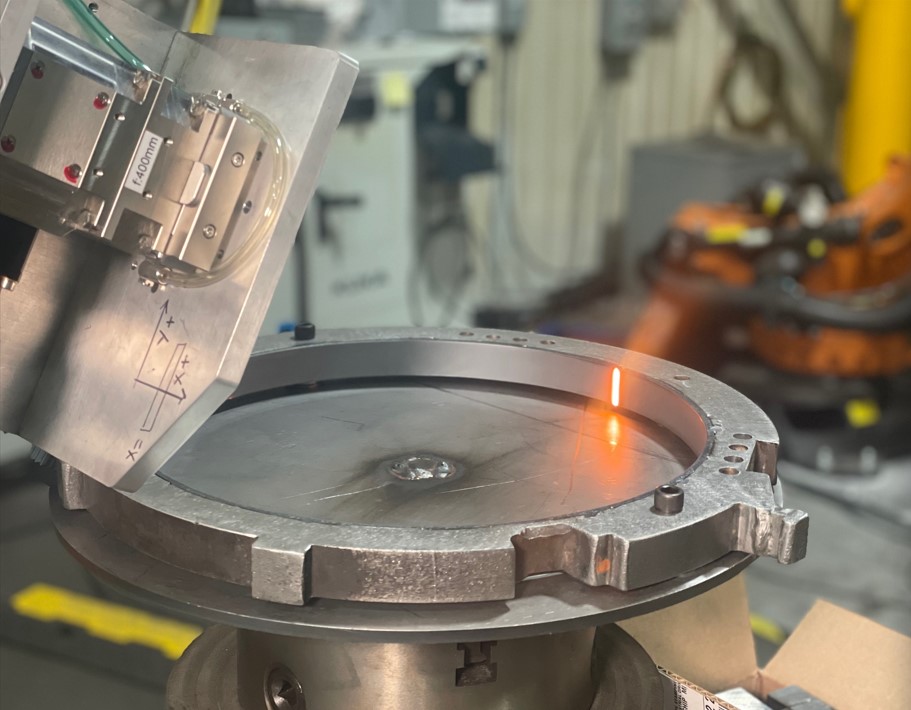

The Solution: Corrosion-Resistant Rotors with FNC

To address recurring rotor corrosion, heat treaters introduced ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC). FNC is a thermal process traditionally used for case hardening, and for brake rotors, it’s used to achieve corrosion resistance.

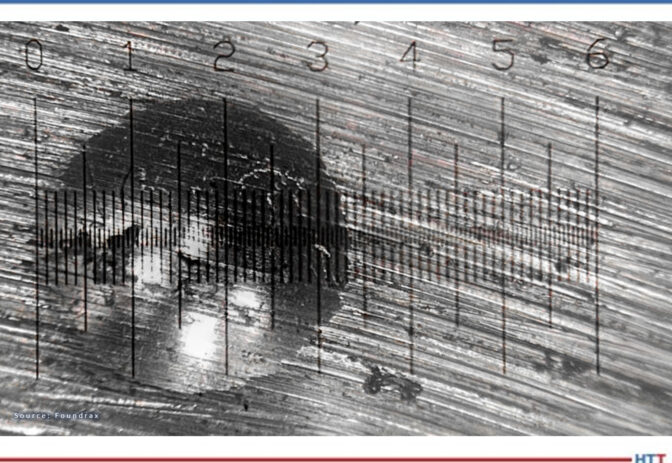

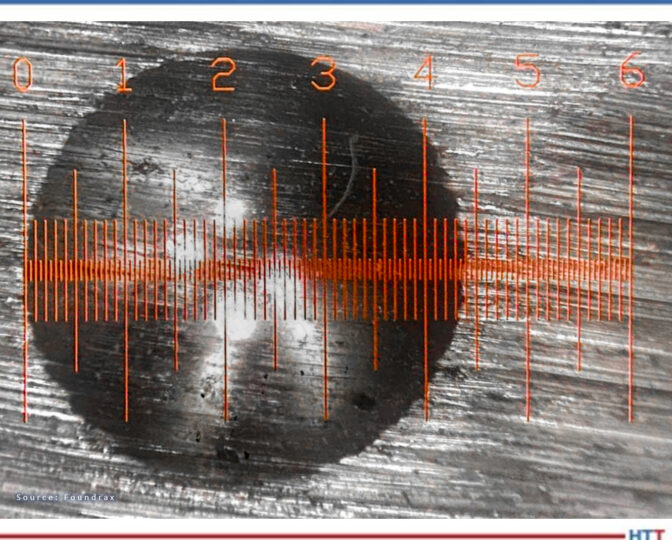

Figure 1 shows a perfect example of the difference that FNC makes. These are pictures of brake rotors from electric vehicles owned by two Paulo team members — one has brake rotors that were ferritic nitrocarburized and show no signs of rust, whereas the other did not go through the FNC process.

Ferritic Nitrocarbonizing Process

FNC is a case hardening technique that uses heat, nitrogen, and carbon to toughen up the exterior of a steel part, improving its durability, decreasing the potential for corrosion, and enhancing its appearance. FNC is unique in that it offers case hardening without the need to heat metal parts into a phase change (it’s done between 975–1125°F). Within that temperature range, nitrogen atoms can diffuse into the steel, but the risk of distortion is decreased. Due to their shape and size, carbon atoms cannot diffuse into the part in this low-temperature process. However, carbon is necessary in the FNC process to generate desirable properties in the intermetallic layer.

Heat Treated Materials for Automotive Seating Components

Safety-Critical Components

Like brake rotors, many automotive seating components (like mechanisms for seat recliners) are here to stay. Thermal processing is used to achieve stringent specifications that are put in place to keep drivers safe in the event of a collision. EV seat components and the thermal processes used to make them crash-ready are identical to those of ICE vehicle components.

Seating Components

Generally, these components are case hardened (either carburized or carbonitrided), typically using one of the following materials:

- 1010 and 1020 carbon steel: These are plain carbon steel with 0.10% carbon content, fairly good formability, and relatively low strength.

- 1018 carbon steel: 1018 is a grade that’s often chosen for parts that require greater core hardness and better heat treatment response than 1010 or 1020.

- 10B21 boron steel: Boron steels are becoming more popular in the automotive industry due to their excellent heat treatment response.

- 4130 alloy steel and 8620 alloy steel: Alloy steels are more responsive to heat treatment than plain carbon steels, so the thermal processing specifications for parts made from these materials are often adjusted to account for the material’s innate strength properties.

Seat Belt Latches

High-strength seat belt latches are usually made from the following materials:

- 4140 and 4130 alloy steels: 4140 alloy steel is one of the most common engineering steels used in manufacturing. For seat latches and hooks, 4140 and 4130 will be neutral hardened to increase their strength and hardness throughout due to the high performance and precision required of these parts.

- 1050 carbon steel: 1050 is a medium carbon steel that contains 0.47–0.55% carbon content. Carbon steels are a less expensive choice when compared to alloy steels such as 4140 or 4130.

Seat Frames and Brackets

Seat frames (also known as seat brackets) give car seats their shape using slender pieces of steel joined together to form the skeleton of the seat. These components are often made from boron steels:

- 10B21 or 15B24 boron steel: These are a good choice for seat brackets because they are only marginally more expensive than other steels used in seating but have impressive toughness, have a good heat treat response, and are weldable.

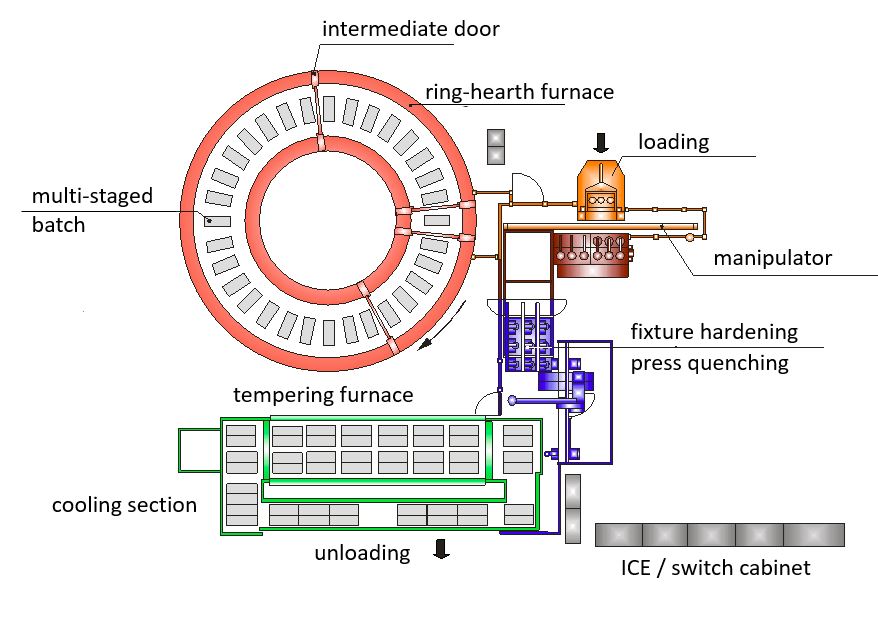

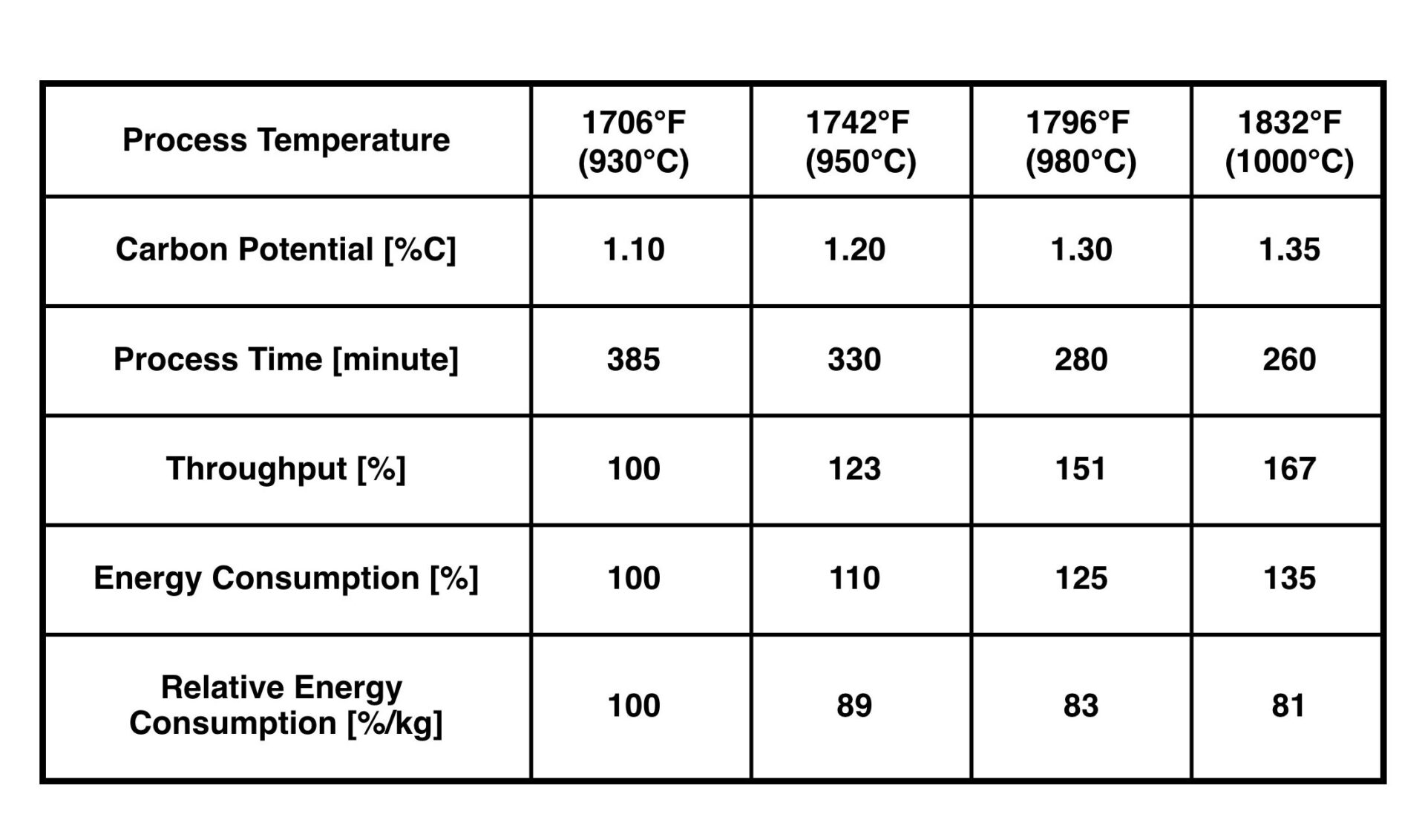

A Closer Look: Case Hardening for Seating Components

Case hardening diffuses carbon or carbon and nitrogen into the surface of a metal from the atmosphere within a furnace at high temperatures. Adding carbon or carbon and nitrogen to the surface of steel hardens a metal object’s surface while allowing the metal deeper underneath to remain softer, creating a part that is hard and wear-resistant on the surface while retaining a degree of flexibility with a softer, more ductile core. This softness and ductility create toughness in parts, allowing them to respond to stress without failing. Case hardening is a general term for this heat treating method. Depending on the materials and specifications for the part, we apply various case hardening techniques, including carburizing and carbonitriding.

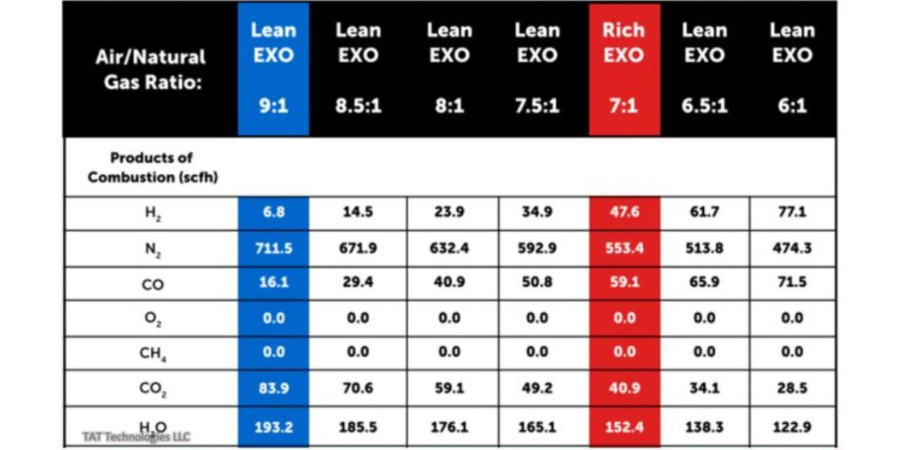

Carbonitriding

During carbonitriding, parts are heated in a sealed chamber well into the austenitic range — around 1600°F — before nitrogen and carbon are added. Because the part is heated into the austenitic range, a phase change occurs, and carbon and nitrogen atoms can diffuse into the part. Carbonitriding is used to harden surfaces of parts made of relatively inexpensive and easily machined or formed steels, which we often see in automotive metal stampings. This process increases wear resistance, surface hardness, and fatigue strength. It is also good for parts that require retention of hardness at elevated temperatures.

Neutral Hardening

Also called through hardening, neutral hardening is a very old method for hardening steel. It involves heating the metal to a specified temperature and then quenching it, usually in oil, to achieve high hardness/strength. In this process, the primary concern is increasing hardness throughout the part, as opposed to generating specific properties between the surface and the core of the part.

All of the metal components of a seat belt, including seat belt loops, tongues, and buckles, are neutral hardened. Specifications typically dictate that these components are hardened to up to 200 thousand pounds per square inch (ksi).

Because seat belt components are visible to the end consumer, their cosmetics are important in addition to their mechanical properties. It’s important to keep the furnace free of soot and thoroughly clean the parts both before and after heat treatment. Proper cleaning readies the part for secondary processing, ensuring the success of activities like polishing and chrome plating.

The Convergence of EV and ICE Vehicles

The EV revolution has significantly transformed automotive manufacturing. Despite these changes, EV parts remain remarkably similar to those of their internal combustion engine (ICE) counterparts. Consequently, any advancements in materials or heat treating processes are swiftly adopted across the entire automotive sector. When it comes to heat treating, innovations are rarely exclusive to EVs.

About the Author:

Metallurgical Engineering Manager

Paulo

Rob provides internal and external customer support on process design, material behavior, job development, reduction of variation, and physical analyses at Paulo. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Metallurgical Engineering from the Missouri University of Science & Technology (formerly known as the University of Mines and Metallurgy) and has worked at Paulo since 1987. Rob has analyzed several million hardness data points and/or process behaviors, leading him to develop many process innovations in the metallurgical field.

For more information: Contact Rob at rsimons@paulo.com.

Find Heat Treating Products And Services When You Search On Heat Treat Buyers Guide.Com

Thermal Processing for EV Components Read More »