Heat Treat Radio #103: US Army Veteran MG T.J. Wright — From Vietnam to Heat Treat

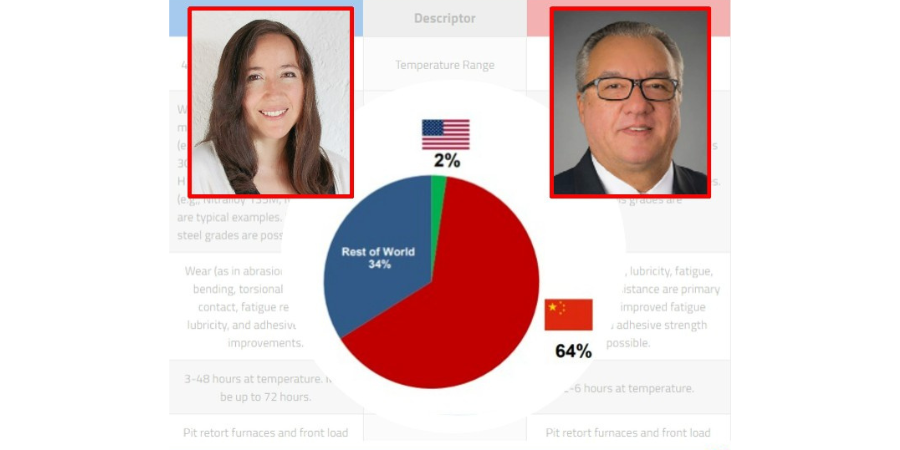

MG Timothy J. Wright (T.J. Wright) understands the heat from a heat treat furnace as well as the heat of engagement in war. As a critical actor in the history of Wirco, Incorporated, T.J. shares his background in the heat treat industry, how this intertwined with a career in the military, and the hallmarks of a life of leadership. Heat Treat Today is honored to bring this Heat Treat Radio episode to pay respect to his long career in the U.S. Army, serving our nation and facilitating peace abroad.

Bethany Leone, managing editor at Heat Treat Today, serves as the special host for today's episode. The episode was sponsored by C3 Data.

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Meet Major General TJ Wright (00:43)

Source: Wright family

Bethany Leone: Let me start off by just sharing a little bit about some bio information about yourself. Could you introduce yourself, who you are, maybe where you grew up?

MG T.J. Wright: My name is Timothy Joseph Wright. I spent my younger years, up until the 8th grade, in Phoenix, Arizona with my family, of which I have three brothers. I moved back to Fort Wayne, Indiana, midterm in the 8th grade year. I went to New Haven High School and worked in a garage for my grandfather in 8th grade and through my sophomore year.

After that, my dad was running a heat treat for a company called National Heat Treat, which doesn’t exist anymore; this was the reason we moved back to Fort Wayne. So, I got a job running tool steel on second shift.

There was a metallurgist there — his name was Carl Bobee — and he taught me how to mount samples and read microstructures, and I learned how to run furnaces. In those days, we took dewpoints with a little dry ice cup in a thing with a thermometer on it. That gives you some concept of how the technology has changed over the last 50 years — it’s pretty amazing.

That caused me and afforded me the ability to get a job after high school as a metallurgical technician working for International Harvester. About midway through my second year working there, I got my notice to come down and take a physical to go here to Indianapolis. When I got to the end, I asked the sergeant, “What does that mean?” and he said, “You’ll probably be back here in 60–90 days; you’ll probably be drafted,” because the Vietnam War was heating up. So, I talked to my dad. He was a WWII vet, as was my grandfather and my uncle. He said if it was me, he would enlist; make it a choice, not chance.

So, I tried to figure out what I was going to do, and I was sitting at home feeling sorry for myself, and a helicopter goes flying across the TV screen and it says the Army is looking for helicopter pilots. I said, “If I’m going, that’s what I’m going to do.” So, I enlisted in the Army, took all the physicals, took the tests, and made the qualification. That’s how my career started.

Source: Wright family

After Enlisting (03:18)

Bethany Leone: When you’re making that decision, it sounds like your family was a big support for you as you’re making that transition to enlist.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes. Family is everything. And after you’re in the service, you learn to recognize that it’s not just your family, but it’s your compatriots and your fellow soldier and airmen’s families too that you care about. It impacts everybody, if something happens, good or bad.

Bethany Leone: What year did you enlist?

MG T.J. Wright: 1966, I believe.

Bethany Leone: And was that before you went to get your college education?

MG T.J. Wright: Correct, yes.

Bethany Leone: How did that come about? Was it through the Army that you decided to?

MG T.J. Wright: I enlisted in the Army, went to Vietnam, and came back from Vietnam. I was an instructor pilot then at Fort Wolters, Texas, where I taught young people — I call them young because I was all of 22 or 23 maybe — how to strap in the helicopter, how to wear the helmet, how to talk on the radio, how to hover. I made helicopter pilots out of them.

People didn’t hardly wear seatbelts in those days. Then, when my time was up (my enlistment of four years) they wanted me to stay in the Army and offered me a direct commission, and I said, “I don’t think I want to go back to Vietnam again, thanks,” so I got off active duty.

In the meantime, while I was in the Army, Lindsey and I got married. We were in Texas and I knew I wanted to be a pilot. Purdue has a great aviation professional pilot program and I applied to go to that. I was accepted and so we spent the next three years at Purdue.

Source: Wright family

I joined the National Guard, at that time, and I was a warrant officer initially. Once again, they offered me a direct commission to become a commissioned officer. So, I accepted it and became a Second Lieutenant.

Vietnam (05:59)

Bethany Leone: Moving back to when you were in Vietnam, because that was your first experience, I imagine it was probably pretty foundational as to how you approached your other deployments.

MG T.J. Wright: It gave me a real insight into being led and leadership. I was in an Air Calvary troopalry, and we had Cobra gunships. We had 086 Scout helicopters and UH 1 Huey liftships and we had an infantry platoon. The mission of the troop was to go out, find bad guys, and kill them. If you needed to put boots on the ground, we would insert our platoon on the ground, and we’d provide them with gunship cover.

enroute to Vietnam 1967

Source: Wright family

I’m trying to remember the exact date, but we were down in the south and we got in a fight with a North Vietnamese regiment (which is a large troop concentration) and there were six silver stars given out that day, which is the nation’s third highest award. I was one of the recipients of it. Five of my other pilots were also recipients that day because there was a lot of heroism going on. There were a lot of aircraft getting shot down and people rescuing other people, blowing up sampans [a type of small, flat-bottomed wooden boat] and shooting people.

Bethany Leone: How long was the engagement?

MG T.J. Wright: It was probably 18 hours. Once it got dark, things kind of settled down and, by then, we got out and had a backup for the 9th Infantry Division and they had inserted several battalions into the area. We provided gun cover for those guys after that, but the initial stage was pretty hectic.

Bethany Leone: I can imagine. Do you remember where you were when you got the mission?

MG T.J. Wright: It was like an everyday mission: We’re going to go down and scout this area out. Then, when we got down there, we almost immediately got engaged and started calling for help to get the whole troop committed.

Bethany Leone: So, when you say it was like a normal day, can you flesh that out a little bit? What did a normal day look like in Vietnam?

MG T.J. Wright: We ran, generally, 24-hour operations. We did night missions and daytime missions, and we always had an aircraft on standby. For instance, one time, I was a standby gunship guy and at about 2 o’clock in the morning they came and woke me up and said, “You’ve gotta go. Call Operations and they’ll brief you on the Ops channel.”

So, I got in the aircraft which had already been preflighted and was ready to go, and I started it up and got airborne. They said there’s an ARVN company, and I read the coordinates and headed south, and they said they’re in contact and they need support. The advisor was asking for Army gunship support.

A little while after that, I got another call from Operations saying there was another ARVN company in the same general location, and they’re also receiving fire, and the advisor was asking for support. As I came up on the area, I could see these tracers going this way and going this way, and I looked at that and I thought about it for a little bit, and I told both of the advisors, “Okay, everybody cease fire.” All the firing stopped — because it was just two ARVN companies that were shooting up one another — and I just turned around and went home.

Bethany Leone: Wow. That kind of decision-making on your part — did you have to do a lot of that often?

MG T.J. Wright: Almost every day. Flying around, the scout guy would be looking for tracks or something, because as soon as they heard you coming, they would go hide, and I would be flying cover for him in case he got shot at. There was a big kind of area — mostly in the Delta — but a big nipa palm tree area near a river, and he was on one end of the palm trees and I was on the other, and I’d go around the corner to the other side and there is a DShKM .51 caliber weapon, on a big tripod, and about five guys, and they’ve got a camo net over it, and they’re trying to pull it off so they can engage me, but I engaged them a little before they ever got it done.

Bethany Leone: Was there a moment, when you were out in Vietnam, when your leadership was really put to the test, a challenging situation? Maybe it was officers you were working with.

MG T.J. Wright: One instance that comes to mind was when we were supporting an infantry battalion. They were on the ground and they were pretty heavily engaged. The battalion commander was in a C&C BIRD command and control aircraft overhead.

It became pretty obvious to me that he had lost perception of what the situation was on the ground. I was pretty aware, as a gunship pilot, about keeping track of what’s going on in the battle. On another frequency, I was telling him where his guys were and what they needed to do, and helped him do what he was supposed to do because he was just not aware of the situation; he’d lost contact with what was going on.

On permanent display at the Indiana War Memorial Museum.

Source: Wright family

The National Guard (12:02)

Bethany Leone: That would’ve been quite dangerous. Stepping in would’ve been quite a key move.

So, then, you said that you came back from Vietnam, married Lindsey, and then you started in the National Guard, at that point.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes. I think I was the second helicopter pilot to join the Indiana National Guard. In those days, they had Korean War vintage aircraft, really old stuff. One of the things that really got me interested was the Vietnam veterans just kept coming, and we had a lot in common, you know? We had a lot of expertise, and it was enjoyable to be around “my guys,” you know?

Bethany Leone: Yes. You go somewhere, you have all those experiences, daily experiences, that are so different from in the U.S. I can imagine the comradery and being able to support each other, also, in coming back.

MG T.J. Wright: It was interesting. You think about, at that point, all these guys had all this experience, as did I, and we would talk; but they were also getting on with their lives, you know? There were mostly a lot of warrant officers and they were going on to be dentists or pilots. It was interesting.

Bethany Leone: Yes, quite interesting.

At some point you were involved in Desert Storm. Where was that in the timeline?

MG T.J. Wright: As time went on, I got a direct commission, and I was a captain. I figured I was ready to be a major and, somehow, in all my assignments, I was an operator so I was involved in doing stuff in, what one would call at that level, the S-3 kind of thing. I ended up on the division staff as a G-1, which is personnel pushing.

I was very unsatisfied with my assignment, and I was pretty vocal about it. One day, the division commander called me into his office and he had this big printout and he said, “Well, when your number (whatever I was, 250th on the promotion list) is up, you’ll get promoted.” And I said, “Well, thank you, sir, but I don’t want to be promoted for just coming to drill.”

I went home that night and I got a call from a guy in the Army Reserve saying, “Hey, we’re looking for an aviator in the 21st Support Command,” and he told me what their mission was and it’s a major’s job. So, I said, “Okay,” and I transferred out of the Guard and went to the Army Reserve.

The Army Reserve (14:33)

It was a great assignment. There were great guys, smart guys. There were lots of opportunities to go overseas and participate with the real 21st Command which is the Support Command for all the European Theater.

We would test alerts. But sitting at home, one Sunday morning, I was having coffee and the phone rang. I answered the phone and they said, “This is a raging bull,” meaning it’s a real thing/alert, and you need to be at the armory as quickly as possible.

We got mobilized to go to Desert Storm, right there on the spot. They took us there, and I think we were there in a couple of weeks, probably.

Bethany Leone: That mobilization — speaking to someone who doesn’t have any experience — what does that look like?

MG T.J. Wright: We immediately sent an advance team to Saudi Arabia, so that we have a touchpoint on the ground. We loaded up all of our equipment, which we didn’t have a lot of. We got a stipend and a laundry list of stuff from General Pagonis’ staff who was the army logistics guy for the entire army in the theater — computers, copy machines, telephones, all kinds of stuff to bring. I was one of the guys that got engaged to purchase all of that stuff and get it ready to go on the 141 and go off to war with it.

In a very short period of time, we committed pretty close to $750,000 in stuff that we needed to take with us. We all packed up on three 141 Starlifters (which is the predecessor to the C-17 today) with all that equipment and all our people, and flew to Roda, Spain, refueled, got back on the airplane and went to Saudi Arabia. We landed in the middle of the night.

Bethany Leone: What was your first impression? I mean, in the middle of the night, you couldn’t really see or be impressed much.

MG T.J. Wright: It was early in the war and before Christmas in 1990. General Pagonis was absconding with everything he could do to fulfill his mission — buying busses, renting buses, trucks, whatever he needed to get — and we put the whole organization on about five school buses and went to Bahrain where we were going to be stationed. We got places to stay, to sleep and rest our heads, kind of thing.

Bethany Leone: It was right before Christmas that you arrived, you said?

MG T.J. Wright: Yes.

Bethany Leone: When you arrived in Bahrain, versus when you arrived in Vietnam, could you feel the difference in setting, in environment?

MG T.J. Wright: Yes. Vietnam was well organized, and you went in and you didn’t know where you were going so you went to the reception station and they gave you a set of orders and told you to go find yourself a cot and we’ll call you when your transportation, to wherever it was you were going, comes. That’s how I got my assignment.

Here, I stayed with the organization that I deployed with, and we all had our separate jobs. I was actually the senior aviation logistician for army aircraft in the theater, as a major; normally, that’s a full colonel’s job. So, I was making sure that we had all the fuel, bullets, parts, and maintenance that was needed.

For instance, I had operational control of 1200 DynCorp guys that were civilian contractors that were doing depot-level maintenance in the theater. We had to refit all the aircraft with filters. The sand was so damaging that we put tape on the rotor blades to keep them from eroding (being sand-blasted) and all kinds of fixes like that, on the spot.

Bethany Leone: When you were in Vietnam, the U.S. had already been there for a couple/few years, but when you let go into Desert Storm for that, you were the frontlines; you were trying to get things moving.

MG T.J. Wright: There was only one Corp. there, at the time we arrived, and they hadn’t deployed yet; they were still camped out in the desert right near where we were. Then, we got the word that the 7th Corp. was supposed to be disbanded, and they were in the process of leaving Europe and coming back to the States and they did a righthand turn with the whole Corp. and brought them to the desert too. So, we had to figure out how we’re going to house, feed and place 300,000 guys and all their equipment.

Bethany Leone: I don’t even want to try and figure out that logistical nightmare!

Logistician for 1700 US Army aircrafts in country

Source: Wright family

MG T.J. Wright: Here’s an example of logistics to think in terms of: You’ve got 700,000 guys in the theater and each of them has two eggs for breakfast, how much oil does it take to cook them?

Bethany Leone: I don’t know! Do you know?

MG T.J. Wright: I don’t know, but I know it’s a truckload.

Bethany Leone: Wow.

So, you arrived before Christmas, and you stayed through the whole operation?

MG T.J. Wright: Yes.

Bethany Leone: What did that look like as it unfolded? There were some peak parts, I’m sure, in January.

MG T.J. Wright: As all the units deployed to their forward staging areas and got ready to start the war, we were doing all of these things that I alluded to with taking care of problems. Normally, we’d get on a set of engines on a Black Hawk or a Cobra engine, you’d get 1,000/1,200 hours on the engine before you’d take it out and overhaul it and put it back in. We were getting about 100 hours on a set of engines. The DynCorp guys were rotating these engines in and out, and they were changing them in the field.

Eventually, what happens is, there is only a specific number of parts available, and we would normally get them back and rebuild them or refurbish them and put them back in the supply system. We didn’t have a method, at that point, to recover those (we called them “repairables”) and get them back in the system. So, I had to develop a system that went to get them and police them up. Initially, I got the Air Force to supply C-130s and I rode around, going to each one of these aviation brigades and policing up all the repairables and bringing them back.

Then, the National Guard brought Sherpas, which is a twin-engine, high-wing, turbo-prop — a little mini cargo plane. I used those guys to not only get repairables back but to deliver parts. I had almost all of the parts that the Army owned in Abu Dhabi. If your aircraft broke or if you needed a part, you would submit a document request, and if it was an AOG (aircraft on ground) kind of part, they would fax a request into St. Louis, which was where the general aviation was managed from. They would put a fax in a fax machine telling the guys in Abu Dhabi to put it on the Sherpa and where to take it. We would get less than a 24-hour turnaround on parts delivery, so it was pretty effective. We had a 90-some percent availability rate, across the board.

One of the things — to give you an idea of what I did — was that when they were briefing General Schwarzkopf on how they were going to start the war, and they were going to use an attack battalion out of the 101st to go in and take the radar stations out so the Air Force could come in and do their attack without getting shot down by the air defense guys.

Lieutenant Colonel Cody, the attack battalion commander, had reached Schwarzkopf so they were going to go into the desert and refuel and attack and then come back out. Schwarzkopf said, “There is no way that you’re going to refuel in the desert.” During the Carter era, we had that Desert One fiasco and the helicopter crashed into the 130 and it was a big mess out there, and he (Schwarzkopf) said. “We’re not doing it. Find another way to do it.”

So, General Pagonis and my boss, Tom Jones, look at me (I’m the aviation guy), and I said, “Well, there’s this thing called the ERF system (Extended Range Fuel system), and I know that there’s 200 of them in Kaiserslautern and we can just send some 141 up to get what we need and unmount a rack of AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, put 300 gallons of fuel on that thing, and then go in and out without refueling, and if you need more missiles, just take more airplanes.” So, that’s exactly what happened.

Bethany Leone: It is quite amazing the logistics, and to be able to make sure that what happens in the field goes down while it needs to. Because you can plan all you want and say we’re going to send in this — these people and this is what they’re going to do — but do they have the fuel for it to come back. Someone needs to be thinking about it and if they don’t, what’s the solution?

MG T.J. Wright: Right. You’ve got to plan for rearming, refueling, recovery of downed vehicles, wounded, and POWs. After the first day of the ground war, we had 80,000 POWs. You’ve got to feed and house these guys, you know? I mean, they were just surrendering like crazy, as fast as they could because they didn’t want to die.

Bethany Leone: To honor that – how do you fulfill that?

How did you end your time with Desert Storm? Was it a slow end or was it a quick in, quick out?

MG T.J. Wright: Well, at the end of the war, the divisions all came back and prepared to redeploy back to their home stations. By then, General Pagonis had been promoted to 4-star and he had a 2-star deputy. We had a huge heliport that we kept these aircraft on but not enough to cover 1700 helicopters. So, I had a plan.

You’ve got to clean these aircraft and make sure there’s no dirt on them and get them ready to ship them back to wherever it was they were going. The deputy called me in one day and said, “You’ve got to find another place to go because I’m taking over the heliport.” His plan was to use that to redeploy all the other equipment — the tanks, APCs, trucks — everything had to be packaged up and ready to redeploy back to home station.

I stood my ground as much as I could with a 2-star general. I got a slice of the heliport and so I reorganized my plan. They would bring their aircraft in and we would wash them and get them ready to redeploy and then fly the aircraft to the port, take the rotor blades off of them, put shrink-wrap over the whole thing, put them on the ship and send them back.

Bethany Leone: How long did that take? How many days or weeks?

MG T.J. Wright: It was a better part of a month, I would say.

Bethany Leone: That’s a lot of equipment to keep count of and store.

MG T.J. Wright: A rotor blade for a Black Hawk helicopter costs about $100,000 and one (helicopter) has five rotor blades on it, I think. When they came over, they put all those rotor blades in shipping containers for rotor blades. But when they got to the desert, they turned those shipping containers upside down and used them for floor tents. So, I had to figure out how to get the rotor blades homes safely.

I didn’t have any chains to chain the aircraft down on the ship so I had to figure all of that out. One of the other guys, Larry McIntyre, who was the “everything else” guy, bought pressure washers — thousands of them. He set up a repair facility and had parts because things would die because they were using them 24/7. He’d change the oil in them regularly.

Bethany Leone: When you get back, and you’re in the National Guard still, what is your rank?

MG T.J. Wright: What happened is, when I came back from Desert Storm, I got a call from the adjutant general chief of staff and he said, “Hey, we want you to come back to the Guard.” I said, “Doing what?” He said, "Well, on the staff, we have a G-1 position,” – which was the reason I left in the first place! And he said, “It’s a lieutenant colonel’s job.” I said, “Okay, I’ll do it.” He said, "You won’t be there long.”

Back to the National Guard (29:31)

Source: Wright family

So, I transferred back to the National Guard, got promoted to lieutenant colonel, and three months later, I got transferred to the Aviation Brigade as the operations officer. I was there three or four months and then they made me commander.

Bethany Leone: As commander, what was your role as commander in seeing these operations?

MG T.J. Wright: It was an interesting time. We talked earlier about all the old aircraft that we had, and in the meantime, we had transitioned to Hueys and OH-58s, but we were positioning ourselves now to get Black Hawks, which is the Army’s premier lift aircraft. I started sending guys to school, transitioning pilots, getting the crew maintenance guys spun up, and looking at maintenance facilities and getting them organized.

Bethany Leone: How long were you in that position?

MG T.J. Wright: I was the brigade commander, I think, for probably 18 months or so, then I got promoted to brigadier general and became the assistant division commander.

Bethany Leone: Again, more strategy planning.

MG T.J. Wright: Higher level expertise, yes.

Bethany Leone: What were some of the responsibilities that came with it, or one of the tasks that you accomplished?

Bosnia and Herzegovina (31:06)

MG T.J. Wright: I wasn’t there very long because I got activated to go take over the U.S. command in Bosnia.

Bethany Leone: How were you chosen, or activated, for that?

MG T.J. Wright: The plan was that, normally, every six months, they would rotate a unit in and out of Bosnia. I was told that we were going to be the last rotation and that the U.S. was leaving Bosnia. My job was to continue the peace enforcement and do a handoff to the EUCOM European theater to take over the mission.

We mobilized an infantry battalion out of the 38th division along with an aviation section, and the staff and I trained here in the States for 30 days, and then we went to Grafenwöhr for 30 days and got some more training spun up, and then we deployed into Bosnia with all of our equipment and people.

Source: Wright family

Bethany Leone: Now, Bosnia and Herzegovina — that part of history is not well covered and I’m sure that people who are listening to our interview would probably appreciate a scope of what that is, at least from your perspective.

MG T.J. Wright: That all started during the Clinton era. He said we’d just be there a year, and we were there far longer than that. The mission was peace enforcement. Peace enforcement is all the protagonists that are involved tell them to ceasefire, and I’m going to force you to ceasefire and I’ve got the horsepower to do it. So, we had the Serbs, the Croats, and the Muslims all shooting at one another in various forms and fashions.

General Đukić, one of the Serbian commanders came to my office one day and he said, “So, if I start to roll my tanks down this road - we were in Tuzla – what would you do?” I said, “Do you see those eight Apache helicopters with the hellfire missiles out there? You wouldn’t make it to my compound, I can tell you that, right now.”

Bethany Leone: So, tension levels were still really high when you got there.

MG T.J. Wright: Not so much. I mean, it’s just probing — stick in to see how you feel. Probably after I was there three months, the realization that we were actually going to leave and things needed to be normalized started to set in. People started saying — leaders, we don’t want you to go. Stop; we want you to stay here. But it was time to go home.

Bethany Leone: I guess that’s kind of how it is once peace is starting to set in, the appreciation for the authority that brought that about is really evident.

MG T.J. Wright: They were very grateful. Serb, Croats, or Muslim, it didn’t matter — they were happy it was going to be over and that they could finally get back to some sense of normalcy.

There were scars, you know. The Serbs, in one fell swoop, killed 6,000 Muslims. They were throwing their bodies in the ground. That’s a lot of bodies. They had mass graves, and we were still finding mass graves when I was there in rotation 15.

We had a “no-knock” policy. Unlike in this country, unless you’ve got a warrant you can’t come into somebody’s house, we could just go in whenever we wanted. We would still find things, because there are still some idiots out there.

Here’s a for instance: One of my guys, in a no-knock search, found a U.S. Army Barrett sniper rifle which is about a $50,000 piece of equipment. It somehow made its way to Bosnia and I’ve got a nice picture of myself shooting that out at the range before we put it back into the supply system.

Bethany Leone: How did you prepare for handling the relationships that you found over there?

MG T.J. Wright: Well, Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided up into three sections: the U.S and, when I was there, the Canadian, and the Spanish had the south. General Bier (who was the Canadian commander), he and I met with our boss, General Packett, and discussed about guidance and what we wanted to do.

One of the things that we implemented was moving people out of the cantonment area (the FOB) into the villages so people would be comfortable and come and tell us where the sniper rifles were hidden and that kind of stuff. That was a very successful program, once we got it launched.

Bethany Leone: I guess, weeding out the unrest in neighborhoods, and bringing the peace to a very immediate personal level for those citizens.

Was there any resistance to that plan?

MG T.J. Wright: I don’t think so. That was always a concern of General Bell. He was the army commander in Europe, and he was my support chain. While I was a U.N. commander (NATO), he frequently visited to make sure he was giving me everything that I needed or wanted. When I told him I was going to do this program, where I put the troops out into the villages, he was not a happy camper; he did not like that idea at all. It was difficult to get the logistics for that organized.

I was telling General Packett that I was getting some resistance from General Bell, and he said, “Well, General Jones,”— who was the SACEUR commander that was coming to see me in a week — “We’ll talk to him about it.” When I told General Jones, he thought it was the greatest thing since sliced butter.

So, General Bell’s habit was every time a 4-star would come and see me, he would come down and get debriefed. I told him that General Bell thought it was a great idea, and he said, “Yeah, I do too!” And he said, "What do you need?” and I said, "Well, I need you to get that thing out of your staff because I’ve got the requirements up there and get it moving.” Within a few days, it started moving again.

Bethany Leone: So, overall, though, your plans, the plans, I guess, of the U.S. and then of NATO, were largely smooth overall, at this point.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes. I learned, by then, that everybody wants to know, after a while, “When are we going home?” Nobody could tell me when we were going home. Sometimes, you can fulfill your own destiny. I just started briefing — when all of these people would come to see me — I’d give them a little slide presentation and say, “We expect to depart on the 14th of December.”

One day, at the Army operation center, they were briefing the on what was going on around the world when the Bosnia thing came up, and they said we planned to depart on the 14th of December, so it became a fact, you know?

Bethany Leone: That’s pretty great! It’s interesting that some decisions aren’t made.

MG T.J. Wright: You can influence it.

Bethany Leone: You can influence it, yes. Some decisions just become as such.

Now, did you have a particular desire to get back, then, as soon as possible, or what were your thoughts on being there versus being with family?

MG T.J. Wright: I think, from a soldier perspective, it was a good rotation. We had good communications. Lindsey and I would text back and forth every night. Soldiers had the same capability. One of the problems that you run into in a situation like that is if it were to be a problem or an issue, everybody has a cellphone. Somehow, you had to shut all that stuff off and clamp down on it until I can tell my boss what’s going on and what’s happening.

One of the things that happened early in the rotation was General Packett told me that he thought there was a PIFWC (Person Indicted for War Crimes) hiding in a town called Pale. So, we airlifted the troops in, surrounded the town, and he gave me a British special operations group to stay in a Serbian church.

General Packett specifically told them no C-4. So, the first thing they did was they went up there and blew the doors off this church. These weren’t just little doors, they were four foot wide, 14 foot tall and three inches thick.

Unfortunately, with all the hubbub going on, the priest and his son were coming down the steps of this church when they blew those two doors off and just about killed both of them, because they got hit by the debris and the doors. Fortunately, they had an emergency medical doctor with them, and they reinflated their lungs and I got them on a medevac and got them to the hospital, and they both survived. But that’s the kind of situation where you don’t want people on their cellphones calling the press telling them what was going on.

Bethany Leone: Absolutely. You don’t want to brew tension from within.

At least to my mind, this is such a very different experience from your experience during the Desert Storm operation. There is still a lot of strategy, I’m sure, but quite different. I don’t know if you could speak to that.

MG T.J. Wright: Well, not only did we have U.S. troops there, but we also had Polish and various other NATO companies and battalions. They had a Turkish battalion, a Polish battalion, a Lithuanian platoon — so there was a lot of international coordination between organizations. Some countries would allow me to tell them to do certain things, and certain things they wouldn’t let them do it. To speak to that and keep all that stuff on track, but by and large, it was dealing with the Polish and the Turks and everybody else was enjoyable. We kept them busy.

Source: Wright family

Bethany Leone: Do you still have contacts from when you were over there?

MG T.J. Wright: Yes. So, General Bier, who retired from the Canadian Armed Forces, is a three-star — he’s been to our place. We have a home in Florida and he’s been down there with his wife, and we’ve been to Canada to visit them.

Bethany Leone: That’s great. It’s such a significant period of time. Specifically, for this instance, you’re working within NATO, you’re coming together for an end goal, and you actually do get to see some peace, by the end of it.

Were you pretty satisfied with how relations left off?

MG T.J. Wright: Oh, yes. I mean, we rounded up a lot of stuff. For instance, one time, in a joint operation with the Canadians, we found a whole cave full of brand new Four-deuce mortars. If you know what a mortar is: It’s a tubelike thing you put a big mortar round in it and it shoots it 8 or 10 miles out. There were probably truckloads full of ammunition to go with it. It was up in a mountain so we had to hotfoot it up and hand carry it all down to get it on the trucks, and then take it to the EOD (explosives ordnance disposal) place. The EOD guys were busy, seven days a week, just blowing up stuff that we would find.

Bethany Leone: Yes, so it doesn’t get blown up somewhere else, essentially.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes, so it doesn’t get used.

Bethany Leone: And the handoff from the North American Treaty Organization of the responsibility of peace to the EUs is not a stabilization force but I forget what the term is for that.

MG T.J. Wright: The general that was in charge of that, for the EU, was a Swedish officer. His staff all spoke English, so that made it enjoyable. It just went smoothly.

We had shipping containers — you see these things going around on trucks — we had about 180 of those setting on the airfield. I had no idea, and nobody on my staff knew what was in them, so when we got the word that it was time to wind this thing down, the bolt cutters went out and started to cut the locks on these shipping containers to see what was in them.

It was just many, many supply issues like mask mounted OH-58 site and radar system; it probably cost two or three million dollars. I was putting all this stuff back into the supply system, and the way it works is that the unit that returns it to the supply system gets credit for it and it goes into your commander’s account.

So, the Title 10 guys in Heidelberg, looking at my commander's account said, “How did you get 54 million dollars in your commander's account?” And I said, “Well, don’t touch that; I’m going to spend it!” Just joking, you know.

Bethany Leone: You had a party to throw!

MG T.J. Wright: As we emptied these containers out, we’d lift them up and put them on a truck and send them back to whoever owned them. I think we found probably six M16s and, later, M4 rifles that were lost, and that was a big deal. If you lose a weapon, you spend weeks looking for it. They were just buried under these shipping containers.

Comments on Afghanistan (47:40)

Bethany Leone: That is interesting. It makes me wonder about your thoughts on the U.S recent pulling out of Afghanistan?

MG T.J. Wright: Oh, it was a debacle.

Bethany Leone: Yes, because just as you’re describing it, from the strategy end, the strategy that happened in Afghanistan, and what we left.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes, it was like we were never there. We left 75 billion dollars’ worth of equipment and left all the people that supported us to the Taliban’s whims.

Bethany Leone: Looking at that situation, especially coming from your background with strategy, how do you think that should have been handled?

MG T.J. Wright: If I was General Milley — and I wasn’t — first of all, giving up the Bagram Air Base — that was a crazy thing. Leaving in the middle of the night, leaving our allies there, not to say a word to them is disgraceful. If we were going to withdraw, that was the perfect place to do it.

I firmly believe that had we left a support contingent to support the administration and the forces, they would’ve been successful because they had the equipment and they had the people. But they needed the intel and they needed some supply support.

But the way it worked out, with all the injuries and the supply people that were killed and maimed, not only just the U.S. forces, but other forces and civilians, I personally would call it a hasty retreat instead of a withdrawal. It was bad.

Bethany Leone: Since you’re in a position to assess that situation, I just wanted to ask that, briefly.

Major General Wright and Heat Treating (49:44)

During all this time in the U.S. Army and the Reserves and the National Guard, did you ever think, “When am I going to get back to my heat treat? What about metallurgy?”

MG T.J. Wright: One of the innate things about the Reserve situation is that everybody is “dual hatted,” so to speak; they have their civilian life and they have their military life. The civilian skills, sometimes, don’t have anything to do with what they do in the Army, but it’s a necessary skill.

Source: Wright family

Here is a for instance: When we deployed to the desert, fax machines had just come out, or fax computer cards by which you could fax stuff over. But there was no way to secure it, so you couldn’t send that information back and forth over a fax line because there was no secure system. One of my compatriots that worked there was a software guy and he worked for Allen-Bradley, and we cut the cord off of a KY-58, which is a secure phone, and we hooked it up to the computer and he made a jumper cable so we could fax that stuff back and forth.

Bethany Leone: Wow.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes, it was pretty cool. He was a smart guy.

He retired as a full colonel and is a good guy. I have friends — I call them our friends at KING FAHD, the guys that I went to Desert Storm with. Once a month, we get together for lunch; we’re still hearing stories about stuff we didn’t know was going on, so it’s interesting.

Bethany Leone: That is quite interesting, yes.

When you went back in the States, can you trace your heat treat involvement?

MG T.J. Wright: I told you my dad ran a heat treat company in Fort Wayne. Fast forward, he got the wherewithal and started his own heat treat in Kendallville, Indiana, called Wirco. In the beginning, it was a struggling organization, you know — cash poor and trying to figure out how to keep the lights on, keep it going, make money, pay the bills, and pay people. My brother, Dennis, worked for him.

Unfortunately, my dad was killed in an aircraft accident, unexpectedly, at age 53 (very young), and my brother was left to run the business. My mom was seriously incapacitated as a result of some surgeries she had, so she was tied to a wheelchair, and so we had to manage her issues. My brother and I talked it over and he suggested that we probably just needed to sell the heat treat company. So, we found a buyer. My brother had to agree to stay there and run the thing for five years.

Source: Wright family

After all the smoke cleared, and everything was said and done, we still had a two-car garage with two welders in it (and welder people and the equipment). I said to him, “What are we going to do with this?” We talked it over and I said, “Well, we used to make our own baskets, maybe we can sell a few.” That was the beginning of Wirco as it exists today.

Bethany Leone: First, what was the name of your father?

MG T.J. Wright: Joseph D. Wright.

Bethany Leone: And, when you talked to Dennis about doing the fabrications of baskets — that was in what year?

MG T.J. Wright: What happened to me was I had a medical issue and I was grounded from the National Guard. When all this happened, it was about that same timeframe.

I was running “Wirco,” the fabrication business. Toward the end of my 12-month they were permanently going to retire me, at that point. My brother came to me and was very unhappy with running the heat treat because of who he worked for, I guess. He wanted to know was there room for him in this fabrication little venture that we had going, and I said, “I don’t think there’s room for both of us, but if you want to run this, I’ll go back to the Army and do that.”

So, that’s what we decided to do. And, over the years, we strategized that we wanted to be the Walmart of suppliers for the heat treating industry. It’s been quite a journey since my dad started Wirco over 50 years ago. We’ve made a lot of decisions along the way.

My brother has a great engineering mind. Rolock, Inc. used to be the standard for baskets, and we were making our baskets out of half-inch 330 and pressure welding the whole thing. They were making their baskets out of three-eighths or quarter-inch rods and stick welding every little stick in place. With every weld point, there is a potential point of failure.

At that time, furnaces went from 18, 24, 12 inches high to 30, 48, 30 inch high baskets. They were big. The requirement for big baskets to be able to handle that kind of material fell right into our timeline, so it worked out well.

Source: Wright family

We were at a heat treating show. . . . You know how you go there and they have all the booths and the glamour and the glitz? Our first heat treating show was DL and I with a 6-foot-long foldup plastic table. The sign on the back was one you get at the show to tell you where your booth is that said Wirco, Inc. — that was us!

Some years later — actually not very long after that — I needed a fulltime job. I went to my brother, who had Wirco moving along, and he gave me a territory. So, I was a representative for Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Bethany Leone: That was probably really beneficial as you knew how to talk the talk with heat treaters and what they needed; you understood their language, given all your experience.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes, we’d get out there and see opportunities. Here’s a for instance: We got into the furnace fan business. Baskets, but also fans.

They’ve done some pretty innovative things, over the years. Furnace fans, of old, all had water-cooled bones on it so it would set into the top or side of the furnace and you’d situate water through the thing. The fan would heat up but keep the bearings cool and keep it from seizing up. I worked with the bearing people, here in Indianapolis, and we got a set of bearings designed with little cooling fans that would sit on the shaft and blow air up through the bearings and did away with the water on the fan. It was pretty cool.

Bethany Leone: I’m sure it probably prevents some distortion by using air instead of water.

MG T.J. Wright: Well, it kept the fan from deteriorating because, generally, the problem wasn’t that the fan failed, it was the corrosion. – the bones would lime up and then it would heat up and then the bearings would seize up and then it would fail.

Bethany Leone: Yes. That’s pretty interesting. There is the strategy mind at work!

The Wright Family (1:00:12)

Could you outline, also, just the different generational ties in heat treat, where they stand now?

MG T.J. Wright: I retired, fully, from everything that I had going on in our lives in 2008. My last assignment, I was J-3 which is the operations officer for the entire National Guard in Washington D.C. When I retired from that, Lindsey and I had a home in Florida, and we had a house here in Indianapolis, and we decided to sell the house in Indianapolis and move fulltime to Florida.

Heat Treat Show Nashville 2017

Source: Wright family

My brother was still running Wirco, and about that time I started encouraging him to think about a succession plan. One of the things that’s interesting is that Chad (who now runs our business for us very successfully, I might add) started working there in grade school, taking the trash out and doing that kind of stuff.

During high school and through college, when he was home, he had different jobs. He was intimately familiar with all the things that went on. He’s not a very good welder but he knows how to weld. We don’t let him touch any of the customers’ products!

He worked in the office for a number of years. Phil Schlenk, my cousin, worked for Wirco; I would call him “the money guy” or the “finance guy.” Phil taught Chad all he knew, brought him up to speed, taught him how to read his balance sheet, and all of the things that are important in keeping the business afloat — making sure you were going to make payroll, etc.

DL retired. I am still on the board, as is DL, and we have board meetings and we have strategy meetings, but Chad has done a remarkable job of growing the company through acquisitions. In the meantime, one of the big things that happened was we bought Alloy Engineering & Casting Company in Champaign, Illinois, which is a foundry, and we still own it. We make castings there and subsequently we bought __Alloys who was a direct basket competitor and we bought Hyper Alloys.

There was a lot of technology, especially when we acquired Hyper Alloys — things that they did that we didn’t know how to do but now we do.

Source: Wright family

Bethany Leone: Chad seems like a really good leader.

MG T.J. Wright: Chad and I had several conversations about leadership, in the beginning, and he had a right basis to start with. I took him to school on leadership and he has just embraced that and he takes care of his people. One of our employees developed cancer — and it was a long-term cancer bout for her; it took over a year to pass, and there was no cure in what she had. Chad, bless his heart, he just continued to pay her, because she needed the money.

Bethany Leone: Really caring for the person beyond the input/output. It’s not transactional, it’s more.

MG T.J. Wright: Chad, when he goes to the plant, every day he walks around the facility. Wirco has three buildings now and they’re not joined together, they’re separate places on the land that they own. He goes to every place, every day and walks around and talks to the people and finds out what’s working and what isn’t. What are your problems, what do we need to do? He’s a good leader, not only people-wise but for the business; he’s got a good business head on his shoulders.

We’re proud of him. I’m proud of the whole team, actually. Erin Fischer runs all of the facilities. He’s “the plant guy.” Derek is a Purdue grad --- he's smart and he is a people person.

A customer doesn’t always get reimbursed for some of the things we do, and we’ve had customers call us up on a Friday afternoon and their furnace is down, and they say, “I don’t have a spare. I’m going to get fired!” Well, bring us the fan; we’ll bring some guys in and build you a new one on Saturday and you can put it in on Sunday and be back to work on Monday.

Bethany Leone: Yes, looking for solutions. The problems are just challenges.

Source: Wright family

Now, your two sons, they also began a business, ancillary to heat treat.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes, it’s very interesting. Nathan, our middle son, I got him a job working for Conrad Kacsik. He’s an instrument guy who goes around and calibrates instruments. He went to school for instruments and took courses in business. He and I were talking one time, and he was calibrating these instruments and I said, “Well, maybe you should start your own business.”

So, we talked it over. One of the big customers that we first took on was the Chrysler Corporation in Kokomo, Indiana. That was the foundation for starting Tru-Cal International and just expanded from there. He’s still doing very well.

Bethany Leone: You must be really proud. Your family — the Wright family — a lot of leaders, a lot of creative thinkers.

C3 Data in Mexico (1:07:15)

MG T.J. Wright: Our youngest son, Matthew, one of the things that Lindsey and I tried to instill in Nathan, though it didn’t take too well on him, was speaking Spanish. Both Matt and are fluent Spanish speakers. When I retired, Matt took over my territory, as a salesman, and after he was there a while, he asked Chad, “Who is our representative in Mexico?” and Chad said, “We don’t have one.” Matt said, “I want the territory.” So, he gets on an airplane and flies himself down to Mexico. Of course, he speaks the language, but getting a lot of the technical terms for “radiant tube” (or whatever) was a challenge. But he was a fast learner and picked all that stuff up.

While he was down there selling Wirco alloy and going to these heat treats, he noted that, unlike in the United States where we have these inspection stickers plastered all over everything, nobody did inspections down there.

So, he called his brother, Nathan, and said, “Hey, here’s an opportunity.” For months, those two would line up these jobs and they would pack up their stuff and get on an airplane and go to Mexico and spend seven days down there working 18 hours a day. After several months of that, they both said, “We can’t keep doing this; this is not going to work.”

He had met Víctor Zacarías that runs GTS now, and he worked for Dana Incorporated, and he asked Victor if he had any interest in coming to work for Nate and him. Víctor said no, he liked his job and he liked his security.

So, on a subsequent trip a month or two later, Víctor was taking Matthew back to the airport, and he said to Matt, “Is that job offer still open?” Matt said, at that point, he was about ready to hang it up, and he said he just looked at the sky and said, “Thank you, God.”

Sons- Nathan and Matthew Wright

Source: Wright family

So, Víctor runs the business down there, now, and it’s very, very successful for those guys. It’s good for the industry.

Bethany Leone: Yes, getting the resources where they need to be. It’s a great partnership, it seems like.

What Does the Future Hold? (1:09:55)

Is there anything, as you look at the heat treat industry, or what your family is doing at Wirco, Tru-Cal, C3 Data, that really excites you about the future?

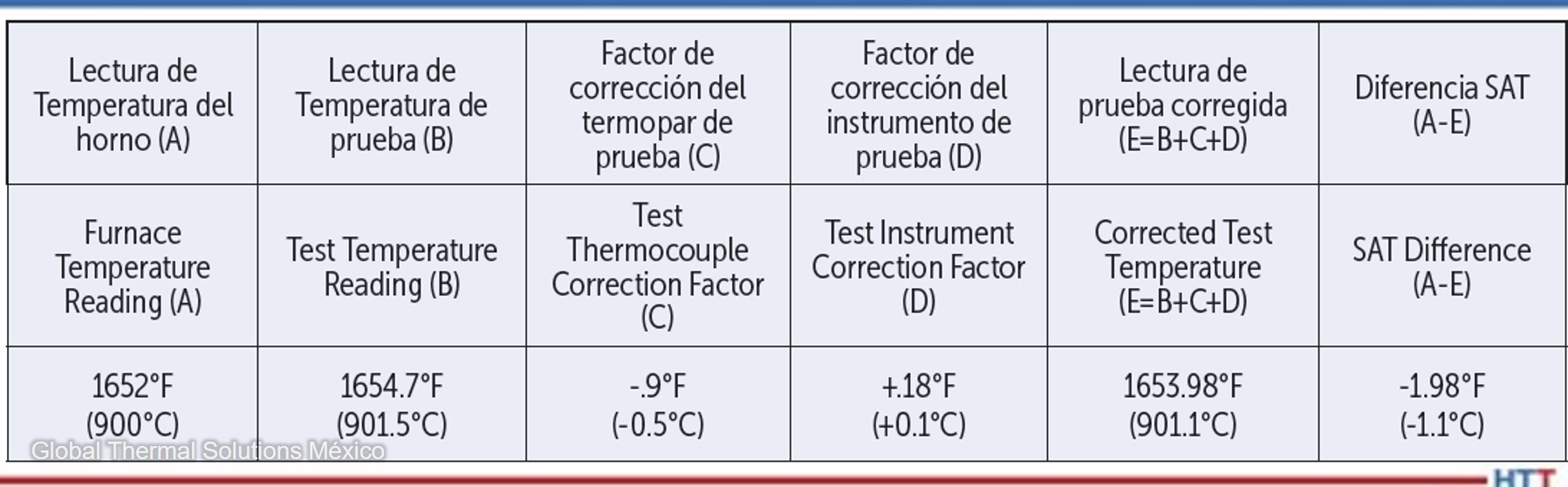

MG T.J. Wright: I think, from Nathan and Matt’s perspective, the software that they’re developing for tracking calibrations and furnace acceptability according to the national standards, they are light years ahead of the industry, as you think about how technology has changed and allowed them to do what they’re able to do.

Before, you would send a technician in there and he’d calibrate all the instruments and he’d take all of these notes and he’d have to go back to his hotel room and write up a report and hopefully didn’t get numbers transposed and just make everything as it’s supposed to be.

Now, as he goes through with his phone and the software, he just plugs in the numbers and sends the report to the Cloud and the customer gets it, right there. He just downloads it off the Cloud and prints it up.

Chad is always looking for ways to improve productivity and make us more efficient. I think between those three young men, they’re an asset to the whole industry.

Bethany Leone: Oh, yes. I think that we’ve recognized all three of them in our rising young leaders of heat treat, at some point or another. Well deserved. If it were possible to nominate people twice, they’d be nominated five times, probably.

MG T.J. Wright: The program that MTI has for training leaders — the YES Program — is such an outstanding program. It allows companies — heat treats, fabricators, or whatever — to send their people up, and they get trained in leadership and making management decisions.

One of the interesting things that I find very interesting about the whole thing is that they’re a bunch of retired military guys. They use the military decision-making process to solve problems. I thought, “I recognize that!” They’re good guys.

Bethany Leone: Is there’s something else — one piece of leadership advice — that you would’ve given to Chad or Nathan or Matt, in any of these last years from the military or your manufacturing career?

MG T.J. Wright: I think they already know this, and they do a good job. But to reemphasize: Your people are who you are, and your people and your families. You start thinking about the effects of a person. Through his efforts, through the labor, he makes the car payment, he makes the house payment, and eventually, you’ll look at that. Chad has got over 150 employees and that’s a lot of house payments and car payments and college tuition bills. A good job and a good work ethic and training people.

You know, welders are one of the key employees that we have. Chad started a program called — I forget what he called it — but he got a T-shirt and tried to recruit young high school guys that didn’t know anything about welding and make them welders. He’s been successful at that. One time, I know we hired a guy right out McDonalds and, a year later, he put him on the payroll fulltime to be a welder.

Bethany Leone: That’s amazing. Changing lives, really.

MG T.J. Wright: Yes.

Speaking about technology and utilizing it, one of the things that Chad does is not only going to heat treating shows, but he sends people to other shows — machine shows and that kind of stuff. We have a huge machining center. When you go to these other shows, you get ideas, like at welding shows, for example.

We make all of our radiant tube wells with a robot. We TIG weld every joint.

Bethany Leone: Well, thank you for being with us, Major.

About the expert: Major General T.J. Wright is a decorated military veteran of the U.S. Army, which he has served in for over half a century. During this time, MG Wright served in both the Vietnam War and Desert Storm, as well as assisting in peace efforts in Europe. Apart from his military service, MG Wright is the founding owner of Wirco, Inc., which is currently run by his nephew, Chad Wright.

Learn more about this episode's sponsor, C3 Data, at www.c3data.com.

To find other Heat Treat Radio episodes, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio.

Search heat treat equipment and service providers on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.com

Heat Treat Radio #103: US Army Veteran MG T.J. Wright — From Vietnam to Heat Treat Read More »