Como se logró la primera horneada de HIP en Latinoamérica

![]()

En diciembre de 2022, se realizó la primera horneada de HIP en suelo latinoamericano. El camino hacia el éxito en HIP, como cualquier usuario de HIP estará de acuerdo, es un camino lleno de baches. ¿Cuáles son los desafíos que deben tener en cuenta los fabricantes aeroespaciales con tratamiento térmico interno al considerar el procesamiento HIP? Aprenda directamente de HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing, un tratador térmico que ejecutó la primera horneada de HIP en la historia de Latinoamérica, cómo navegaron la transición desde trabajos pequeños de herramentales hasta el procesamiento HIP para piezas aeroespaciales.

En diciembre de 2022, se realizó la primera horneada de HIP en suelo latinoamericano. El camino hacia el éxito en HIP, como cualquier usuario de HIP estará de acuerdo, es un camino lleno de baches. ¿Cuáles son los desafíos que deben tener en cuenta los fabricantes aeroespaciales con tratamiento térmico interno al considerar el procesamiento HIP? Aprenda directamente de HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing, un tratador térmico que ejecutó la primera horneada de HIP en la historia de Latinoamérica, cómo navegaron la transición desde trabajos pequeños de herramentales hasta el procesamiento HIP para piezas aeroespaciales.

Read the Spanish translation of this article in the version below, or see both the Spanish and the English translation of the piece where it was originally published: Heat Treat Today's March Aerospace Heat Treating print edition.

Si quisieras aportar otros datos interesantes relacionados con HIP, nuestros editores te invitan a compartirlos para ser publicados en línea en www.heattreattoday.com. Puedes hacerlos llegar a Bethany Leone al correo bethany@heattreattoday.com

De herramientas simples al tratamiento térmico aeroespacial

Founder and CEO

HT-MX

Escribir esta historia de como llegamos a ser la primera compañía latinoamericana en ofrecer prensado isostático en caliente acreditado por NADCAP trae a la mente una avalancha de recuerdos e imágenes. Los comienzos de HT-MX fueron simples, pero también llenos de desafíos, fracasos y lecciones. Cuando comenzamos la compañía, estábamos seguros de que, aunque éramos pequeños, éramos una “planta de tratamiento térmico” y no solo un taller.

Estando ubicados en México quiere decir que hay grandes plantas con corporativos lejos de aquis — clientes potenciales — que estarían decidiendo sobre su proveedor de tratamiento térmico lejos de nuestra ubicación. Trabajamos arduamente para ser y presentarnos como profesionales y confiables. Pero pronto aprendimos que lograr la confi anza con los clientes requiere mucho más que un buen discurso y una planta limpia.

Como era de esperar, los primeros trabajos fueron trabajos simples de herramentales, algunos templados y revenidos de herramentales y carburizado de engranes. Recuerdo como un ingeniero junior y yo dábamos la vuelta en mi viejo hatchback alrededor de talleres locales y recogíamos un pequeño eje o engranaje y lo llevábamos de regreso a la planta. Nos emocionábamos mucho cuando lográbamos la profundidad de capa correcta.

Source: HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing

Con recursos mínimos, decidimos implementar el sistema de calidad nosotros mismos. Nos hicimos amigos de un gerente de calidad de una empresa local, venía a ayudarnos los fines de semana o después de las 6:00 p.m. hasta que llegó la fecha de la auditoría. Su enseñanzas aún se usan en HT-MX hasta el día de hoy. Recuerdo celebrar con una “Carne Asada” cuando terminamos esa primera auditoría, pensando que habíamos dado un gran paso adelante, sin darme cuenta de lo lejos que aún estábamos de nuestra visión.

Con el tiempo, dirigimos nuestra atención a la industria aeroespacial en Chihuahua, una ciudad con cuatro OEMs. Recibimos la certificación AS9100 y comenzamos a trabajar en la acreditación NADCAP. Esto requirió tiempo, pero para entonces contábamos con un equipo de Ingenieros bastante sólido y obtuvimos con éxito la acreditación de NADCAP a finales de 2019. Nuevamente, celebramos con una Carne Asada, esta vez con una mejor comprensión de dónde estábamos y qué futuros desafíos tendríamos que enfrentar.

Entrándole al Prensado Isostático en Caliente

La pandemia llegó. La crisis del 737 Max de Boeing continuó afectando a la industria. Empezar en sector aeroespacial fue lento y con un volumen limitado, especialmente en comparación con lo que habíamos visto en la industria automotriz y de oil&gas. Pero para entonces, las empresas internacionales estaban más dispuestas a trasladar las operaciones de tratamiento térmico a proveedores mexicanos, y estábamos listos, comenzando a procesar aluminio, endurecimiento por precipitación, recocido y otros procesos estándar. Fue durante estos inicios en la industria aeroespacial que escuchamos hablar del prensado isostático en caliente (HIP) por primera vez.

Alrededor de 2019, durante un evento del Cluster Aeroespacial de Chihuahua, un OEM con presencia local se acercó a nosotros con sus requerimientos de HIP. No conocíamos mucho de HIP, pero de inmediato me interesé . . . ¡hasta que descubrí cuánto cuesta una de esas máquinas!

Pero un buen financiamiento a través de programas gubernamentales ayudó a hacer realidad este proyecto de HIP. El momento no fue el mejor, ya que las elecciones federales en México causaron una depreciación temporal de la moneda mexicana, lo que obstaculizó el proyecto al principio.

Source: HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing

Obtener las certificaciones y validaciones adecuadas resultó ser un proceso largo y complejo también. Teóricamente, sabíamos qué esperar en términos de obtener la aprobación para el checklist de NADCAP, pero la realidad fue un poco diferente. Obtener la certifi cación de NADCAP construye lentamente una determinada cultura en cualquier empresa en sus actividades diarias. Traducir esa cultura a una unidad de negocio completamente diferente, con un nuevo equipo y un nuevo proceso, demostró traer sus propios desafíos.

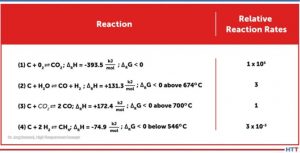

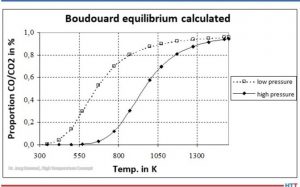

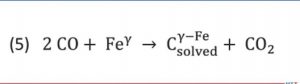

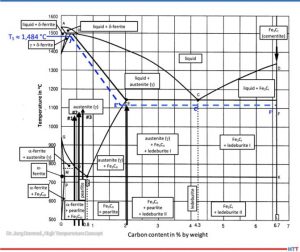

Retos en el HIP: presión, temperatura, termopares y argon

El tratamiento térmico generalmente trata de temperatura, control de la atmósfera (o la falta de ella) y los requisitos regulares de trazabilidad. HIP, sin embargo, agrega algunas dimensiones nuevas a lo que normalmente vemos: presión interna, temperaturas muy altas, de hasta 3632°F (2000°C) y suministro de argón. Fue la primera vez que HT-MX lidiaba con un proceso que incorporaba hasta 30,000 psi y también usaba mucho argón de alta pureza.

La presión tiene sus propios desafíos, aunque la prensa de HIP se encarga de ellos. Aún así, el funcionamiento interno en este tipo de prensas es fundamentalmente diferente al de un horno de tratamiento térmico regular. Sí, necesitas calentarlo, pero aparte de eso, no es ni siquiera un horno, sino una prensa. Comprender cómo funciona la máquina, qué sucede dentro con toda esa presión, cómo afecta a los componentes sometidos a prensado isostático en caliente y cómo afecta a las canastas y fi xtures que estás utilizando, es una curva de aprendizaje crítica.

Las altas temperaturas cambian todo sobre el funcionamiento de estos tipos de ciclos. Trabajamos con metales, lo que significa que las temperaturas oscilan entre 1832°F y 2372°F (1000°C y 1300°C). Esto tiene un impacto en la selección de termopares, calibración y más; con los proveedores de termopar basados en EUA, esto implica más desafíos y costos adicionales. He perdido la cuenta cuantos viajes urgentes de ida y vuelta por refacciones a la frontera he hecho. ¡Es un viaje redondo de 800 km! Afortunadamente, hemos encontrado un gran proveedor que nos ha ofrecido la retroalimentación técnica que necesitábamos, y finalmente hemos comenzado a comprender y controlar nuestro consumo de termopares. Aunque, debo ser honesto aquí, todavía tenemos mucho que aprender en este aspecto.

Luego está el suministro de argón. En HT-MX nunca esperamos que fuera un desafío, pero resulta que conseguir el proveedor adecuado, un que entienda los requisitos y esté dispuesto a trabajar contigo desde la validación hasta la producción, es clave. Es posible que puedas iniciar tu proceso de validación usando argón transportado en contenedores de gas, pero eventualmente necesitarás cambiar a argón líquido. Eso resultó ser más difícil de lo esperado. No hay muchos proyectos que requieran este tipo de alianzas a nivel local. Conseguir el proveedor adecuado fue clave y resultó ser un desafío mayor de lo esperado. Y luego vinieron las lecciones sobre cómo utilizar eficientemente el argón líquido, evitar el excesivo venteo del tanque y ser inteligente con el calendario de HIP en general. Esto ha sido un proceso de aprendizaje constante, uno que tiene altos costos.

Últimos obstáculos: certificaciones, eventos globales y costos energéticos

Una vez que nuestra empresa obtuvo la certificación NADCAP, todavía necesitábamos la aprobación de los OEM para el proceso HIP, luego la aprobación para la versión específica del proceso HIP y luego la aprobación real para los números de parte.

Estas aprobaciones fueron manejadas por el departamento de ingeniería del corporativo y no localmente. Fue un proceso que consumió mucho tiempo, con varias pruebas, pruebas de laboratorio, múltiples auditorías, visitas y más pruebas, etc. Y mientras todo esto sucedía, todavía teníamos que diseñar la operación, localizar proveedores críticos que no estaban disponibles en México, crear alianzas con proveedores, etc. Escribir esto en pocas líneas parece más simple y rápido de lo que realmente fue.

Source: HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing

Además, en casos como este, las empresas mexicanas, especialmente las pequeñas, enfrentan mucho más escrutinio que las empresas estadounidenses o europeas, y deben probarse en cada paso. Tiene sentido, aunque se siente un poco injusto, ya que HT-MX no tenía un historial comprobado de procesos de alta tecnología como HIP. Cuesta tiempo extra, cuidado adicional y a veces pruebas adicionales, pero es la realidad que enfrentamos y debemos superar los obstáculos adicionales.

Mientras navegábamos en la aprobación de HIP, llegó la pandemia. Meses después, comenzó la guerra en Europa con impactos significativos en el costo de la energía. Nuestros principales clientes eran de alto volumen y bajo margen, y con el aumento de los precios de la energía, nuestra competitividad comenzó a disminuir. Para adaptarnos y evolucionar, decidimos agregar algunos hornos más pequeños para piezas más pequeñas, invertir en capacitación y aumentar los esfuerzos de ventas y enfocarnos en clientes basados en AMS / NADCAP, dejando ir a clientes principales. Poco a poco, las cosas comenzaron a mejorar.

La Primera Horneada Ofi cial de HIP en la Historia de Latinoamérica

En diciembre de 2022, HT-MX llevó a cabo la primera horneada oficial de HIP en la historia de Latinoamérica. Tomo bastante tiempo. Siempre pensé que hacer esa primera horneada se sentiría como llegar a la cima del Everest. Cuando llegó el día, solo se sintió como llegar al campamento base del Everest. Todavía nos queda mucho camino por recorrer para ser realmente un proveedor de HIP establecido. Ahora, volvemos a escalar y apuntamos a esa cima, esa cima que perpetuamente precederá a la próxima cima.

Todavía hay varios desafíos: estabilizar nuevos procesos y mejorar los establecidos. Pero estoy seguro de que avanzaremos en esta nueva etapa. Y estoy muy emocionado por la próxima Carne Asada.

Acerca del Autor:Humberto Ramos Fernández es un ingeniero mecánico con una maestría en Ciencia. Tiene más de 14 años de experiencia industrial y es el fundador y actual CEO de HT-MX Heat Treat & HIPing, que se especializa en tratamientos térmicos de atmósfera controlada, con certifi cación NADCAP, para las industrias aeroespacial, automotriz y de petróleo y gas. Con clientes que van desde OEM hasta Tier 3, el Sr. Ramos tiene una amplia experiencia en el desarrollo de procesos secundarios específi cos de alta complejidad para los requisitos más exigentes.

Contacto Humberto humberto@ht-mx.com

Find heat treating products and services when you search on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.com

Find heat treating products and services when you search on Heat Treat Buyers Guide.com

Como se logró la primera horneada de HIP en Latinoamérica Read More »