Nitruración anódica por plasma de aleaciones de titanio

En esta entrega de Martes Técnico, el Dr. Edward Rolinski y Dan Herring, conocidos respectivamente como “Doctor Glow” y The Heat Treat Doctor®, exploran cómo el nitrurado por plasma anódico para aleaciones de titanio evita los efectos dañinos del nitrurado catódico convencional mientras mejora la resistencia al desgaste, la resistencia a la corrosión y la confiabilidad de los componentes para aplicaciones aeroespaciales y médicas.

Este artículo informativo se publicó por primera vez en Heat Treat Today’s November 2025 Annual Vacuum Heat Treating print edition.

Para leer el artículo en inglés, haga clic aquí.

La nitruración tradicional por plasma/iónica es una tecnología consolidada. Sin embargo, presenta problemas que pueden solucionarse con el nuevo método de nitruración anódica por plasma. Este artículo presenta la idea de utilizar la nitruración anódica por plasma para titanio y aleaciones de titanio, evitando así los efectos perjudiciales de la nitruración catódica por plasma convencional. Descubra cómo este enfoque podría proporcionar capas más duras y sin defectos que mejoran el desgaste, la resistencia a la corrosión y la fiabilidad general de los componentes para piezas críticas de la industria aeroespacial y médica.

Qué es la nitruración anódica?

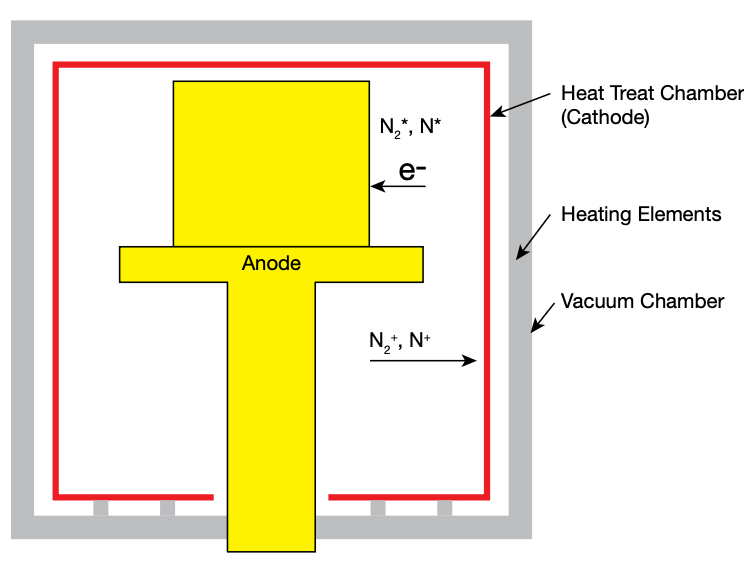

La nitruración anódica es un tipo de proceso de nitruración por plasma en el que las piezas tratadas se ubican en un potencial anódico (positivo) en lugar del potencial catódico (negativo) habitual. A diferencia de la nitruración por plasma convencional (descarga catódica), donde el componente se bombardea con iones positivos de alta energía, la nitruración anódica implica el bombardeo de electrones de baja energía sobre la superficie del componente.

La nitruración anódica es particularmente efectiva para materiales con una alta energía libre estándar negativa de formación de nitruros (p. ej., titanio, circonio), ya que ayuda a evitar o reducir el efecto de borde, un problema bien conocido en la nitruración catódica que provoca un bombardeo iónico desigual y endurecimiento en esquinas y bordes.

Antecedentes: Complejidades de la nitruración por plasma

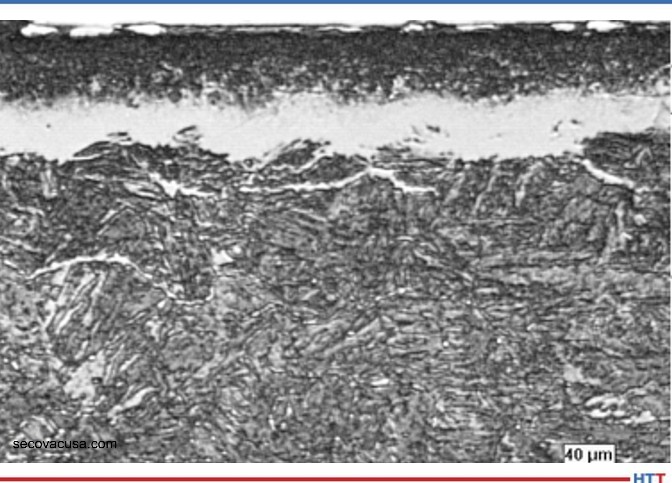

La nitruración por plasma con descarga luminiscente se aplica a una amplia gama de materiales, como fundiciones, aceros al carbono, aceros inoxidables, níquel, aleaciones de titanio y pulvimetalurgia (Roliński, 2014). Los procesos de nitruración por plasma y nitrocarburación permiten la formación de capas superficiales con propiedades tribológicas superiores (Roliński, 2014). Sin embargo, la cobertura de las piezas con la descarga luminosa no siempre es uniforme, especialmente cuando se procesan cargas de geometría compleja (véase la Figura 1).

Source: Roliński and Herring

Source: Roliński and Herring

La nitruración por plasma de baja descarga es un tratamiento termoquímico que utiliza partículas de alta energía. Los iones de nitrógeno u otras especies gaseosas se aceleran y ganan energía en el espacio oscuro de Crookes (CDS) alrededor de la pieza, que es el cátodo en una configuración de electrodos de corriente directa. Primero activan la superficie mediante pulverización catódica (sputtering) para eliminar cualquier óxido nativo presente. El tratamiento de pulverización catódica también genera una cantidad sustancial de partículas sólidas, generadas por la propia pieza, incluyendo átomos metálicos que flotan cerca de la superficie (Merlino y Goree, 2004; Roliński, 2005). En el procesamiento del titanio, por ejemplo, esto afecta tanto la adsorción como la difusión en la superficie, creando condiciones que degradan la calidad de la capa (Hubbard, et al., 2010). Se ha descrito un impacto negativo de este plasma “polvoriento” en la uniformidad de la capa nitrurada en piezas de geometría compleja (Ossowski et al., 2016).

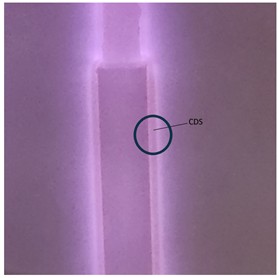

Además, es bien sabido que durante la nitruración por plasma se observa el denominado efecto esquina/borde (EE), relacionado con la circulación desigual de estas partículas de polvo alrededor del cátodo (véase la Figura 2). En situaciones extremas, especialmente al tratar piezas de geometría compleja, el EE, causado por una distribución desigual del campo eléctrico en esquinas, cavidades, etc., da lugar a una distribución excesiva y desigual de estos depósitos de plasma (PD). De esta manera, el EE agrava el problema ya existente de la redeposición, lo que provoca la formación de diversos microdefectos y un espesor desigual de la capa nitrurada (Merlino y Goree, 2004; Roliński, 2005, 2024; Ossowski et al., 2016).

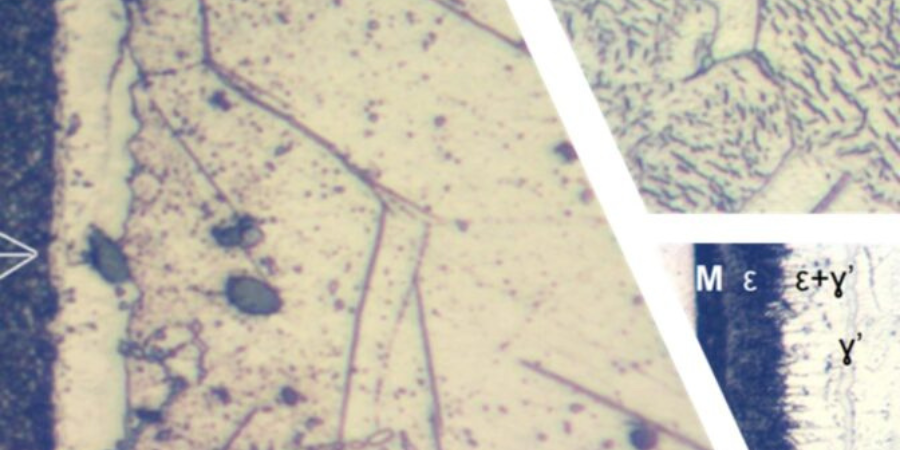

La nitruración por plasma del titanio se realiza habitualmente a 680–1100 °C (1256–2012 °F). Entre los aspectos negativos del uso de la polarización catódica en titanio se incluyen el bombardeo de plasma/iónico, que provoca daños superficiales debido principalmente a micro-arcos y la contaminación de la superficie con los compuestos depositados, así como su distribución desigual debido al EE (Merlino y Goree, 2004; Roliński, 2005, 2014, 2024; Ossowski et al., 2016). Aunque el arco eléctrico se ha eliminado mediante la aplicación de técnicas de plasma pulsado, la pulverización catódica solo se puede controlar de forma limitada, especialmente cuando se nitruran piezas de geometría compleja. Por lo tanto, la nitruración gaseosa en amoníaco se ha utilizado ocasionalmente para endurecer piezas de titanio. Se produce un aspecto dorado resultante en la superficie que indica la presencia del nitruro TiN (véase la Figura 3).

Nitruración anódica de aleaciones de titanio

Se han realizado investigaciones sobre la nitruración anódica de aceros por plasma (Zlatanovic 1986; Michalski 1993; Kenĕz 2018). El amoníaco o las especies de nitrógeno activo generadas en el plasma pueden nitrurar el ánodo al igual que al cátodo. Las especies activas que causan la nitruración son átomos de nitrógeno activo y radicales NH altamente reactivos (NH*) formados en el plasma cercano. Los radicales NH (también conocidos como radicales imidógenos) son especies químicas con un enlace nitrógeno-hidrógeno junto con un electrón desapareado. En el caso del titanio, el hidrógeno debe excluirse en muchas situaciones, ya que reacciona con el titanio para formar hidruros estables que fragilizan el producto (Roliński, 2015).

La entalpía libre estándar de formación de nitruros de titanio tiene un valor negativo excepcionalmente alto, lo que significa que el nitruro de titanio se formará espontáneamente cuando el ánodo de titanio reaccione con nitrógeno excitado cercano (Roliński, 2015). Cambiar de polarización catódica a anódica de los componentes tratados ofrece varias ventajas notables. Una descarga luminosa en nitrógeno puro o argón genera únicamente iones positivos que se aceleran hacia el cátodo/pieza de trabajo. Dado que estas mezclas de gases carecen de iones negativos, solo los electrones de la luminiscencia anódica inciden en el ánodo/pieza de trabajo. Esto produce la activación de la superficie sin los efectos negativos de las colisiones de partículas más pesadas, como N₂+ (es decir, un ion molecular de nitrógeno con carga +1), lo que provoca una pulverización catódica excesiva. Al mismo tiempo, partículas de nitrógeno sin carga, como N₂* y N*, reaccionan con el ánodo por quimisorción en la superficie a una temperatura suficientemente alta, lo que finalmente conduce a la formación de la capa de difusión.

Se cree que el proceso de nitruración anódica puede tener efectos positivos en el tratamiento de piezas de precisión de titanio y otras aleaciones para su uso en las industrias aeroespacial y médica. Este método permitirá el tratamiento a la temperatura más baja posible gracias a la activación de la superficie con los electrones de la polarización anódica. La textura, la apariencia y una superficie sin defectos producirán una pieza superior y mejorarán el rendimiento de muchos de esos componentes. Esto será importante cuando la corrosión o las propiedades ópticas de la superficie sean importantes.

La nitruración anódica del titanio puede lograrse mediante un sistema convencional de nitruración por plasma, siempre que el ánodo central esté diseñado y ubicado adecuadamente. Este ánodo, o parte del mismo, debe estar hecho de titanio para evitar la evaporación y la transferencia de impurezas a las piezas.

Aplicaciones

Las aleaciones de titanio son populares en ortopedia debido a su elasticidad, resistencia y biocompatibilidad similares a las del hueso (Roliński 2015; Froes 2015). Los procesos de ingeniería de superficies, como la nitruración anódica, pueden desempeñar un papel importante a la hora de prolongar el rendimiento de los dispositivos ortopédicos varias veces más allá de su vida útil normal.

Los materiales intermetálicos superelásticos, como el 60NiTi, se utilizan en elementos de rodamientos debido a su resistencia a la corrosión y al impacto (Pohrelyuk et al., 2015; Corte et al., 2015). Suelen ser propensos a la degradación por fatiga de contacto rodante (RCF). Cualquier defecto superficial presente en estos componentes, como la concentración local de impurezas o microfisuras, provocará un fallo prematuro. La nitruración por plasma anódico puede utilizarse para endurecer las superficies de los componentes de rodamientos fabricados con estas aleaciones, formando una capa dura y sin defectos, lo que puede mejorar sus propiedades ante el RCF.

Se espera que las piezas de titanio u otras aleaciones con la superficie sometida a nitruración anódica estén libres de micro-defectos, lo que permite su amplia aplicación en el campo médico, la industria aeroespacial y los dispositivos ópticos y semiconductores.

Referencias

Corte, Ch. Della, M. K. Stanford, and T. R. Jett. 2015. “Rolling Contact Fatigue of Superelastic Intermetallic Materials (SIM) for Use as Resilient Corrosion Resistant Bearings.” Tribology Letters 26: 1–10.

Froes, F. H., ed. 2015. Titanium: Physical Metallurgy, Processing and Applications. Materials Park, OH: ASM International.

Hubbard, P., J. G. Partridge, E. D. Doyle, D. G. McCulloch, M. B. Taylor, and S. J. Dowey. 2010. “Investigation of Mass Transfer within an Industrial Plasma Nitriding System I: The Role of Surface Deposits.” Surface and Coatings Technology 204: 1145–50.

Kenĕz, L., N. Kutasi, E. Filep, L. Jakab-Furkas, and L. Ferencz. 2018. “Anodic Plasma Nitriding in Hollow Cathode (HCAPN).” HTM Journal of Heat Treatment and Materials 73 (2): 96–105.

Merlino, R. L., and J. A. Goree. 2004. “Dusty Plasmas in the Laboratory, Industry, and Space.” Physics Today, July, 32–38.

Michalski, J. 1993. “Ion Nitriding of Armco Iron in Various Glow Discharge Regions.” Surface and Coatings Technology 59 (1–3): 321–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0257-8972(93)90105-W.

Ossowski, Maciej, Tomasz Borowski, Michal Tarnowski, and Tadeusz Wierzon. 2016. “Cathodic Cage Plasma Nitriding of Ti6Al4V.” Materials Science (Medžiagotyra) 22 (1).

Pohrelyuk, I., V. Fedirko, O. Tkachuk, and R. Poskurnyak. 2015. “Corrosion Resistance of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy with Oxidized Nitride Coatings in Ringer’s Solution.” Inzynieria Powierzchni (Surface Engineering) 1: 38–46.

Roliński, E. 2014. “Plasma Assisted Nitriding and Nitrocarburizing of Steel and Other Ferrous Alloys.” In Thermochemical Surface Engineering of Steels, edited by E. J. Mittemeijer and M. A. J. Somers, 413–57. Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering 62. Cambridge, UK; Waltham, MA; and Kidlington, UK: Woodhead Publishing.

Roliński, E. 2015. “Nitriding of Titanium Alloys.” In ASM Handbook, Volume 4E: Heat Treating of Nonferrous Alloys, edited by G. E. Totten and D. S. McKenzie, 604–21. Materials Park, OH: ASM International.

Roliński, Edward. 2024. “Practical Aspects of Sputtering and Its Role in Industrial Plasma Nitriding.” In ASM Handbook Online, Volume 5: Surface Engineering. Materials Park, OH: ASM International. https://doi.org/10.31399/asm.hb.v5.a0007039.

Roliński, E., J. Arner, and G. Sharp. 2005. “Negative Effects of Reactive Sputtering in an Industrial Plasma Nitriding.” Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 14 (3): 343–50.

Zlatanovic, M., A. Kunosic, and B. Tomčik. 1986. “New Development in Anode Plasma Nitriding.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ion Nitriding, Cleveland, OH, September 15–17, edited by T. Spalvins, 47–51. Cleveland, OH: NASA Lewis Research Center.

About The Authors:

“Doctor Glow”

El Dr. Edward Rolinski, conocido afectuosamente como “Doctor Glow”, es un distinguido científico sénior que ha liderado la investigación sobre nitruración por plasma/iones desde la década de 1970. Posee títulos avanzados en tecnología de fabricación y metalurgia, incluyendo un doctorado en Ciencias. Se ha centrado en los procesos de nitruración por plasma, especialmente en aleaciones de titanio y pulvimetalurgia. A lo largo de su carrera, el Dr. Rolinski ha sido autor de numerosos capítulos y artículos técnicos influyentes, incluyendo para ASTM International y el Manual ASM, y es un prolífico colaborador en publicaciones del sector. Tras décadas de liderazgo e innovación en ingeniería de superficies y tratamiento térmico, ahora es un consultor en la industria del tratamiento térmico.

(The Heat Treat Doctor®)

The HERRING GROUP, Inc.

Dan Herring, conocido como The Heat Treat Doctor®, lleva más de 50 años en la industria. Dedicó sus primeros 25 años al tratamiento térmico antes de fundar su empresa de consultoría, The HERRING GROUP, en 1995. Su amplia experiencia en el campo abarca la ciencia de los materiales, la ingeniería, la metalurgia, el diseño de equipos, la especialización en procesos y aplicaciones, y la investigación de nuevos productos. Es autor de seis libros y más de 700 artículos técnicos.

Para más información: Contacte con Dan en dherring@heat-treat-doctor.com.

Nitruración anódica por plasma de aleaciones de titanio Read More »

Source:

Source: