The future of heat treating requires new manufacturing solutions like robotics that can work with modular design. Yet so also does temperature monitoring need to be seamless to know how effectively your components are being heat treated — especially through being quenched. In this Technical Tuesday, learn more about temperature monitoring through the quench process.

Gas Carburization

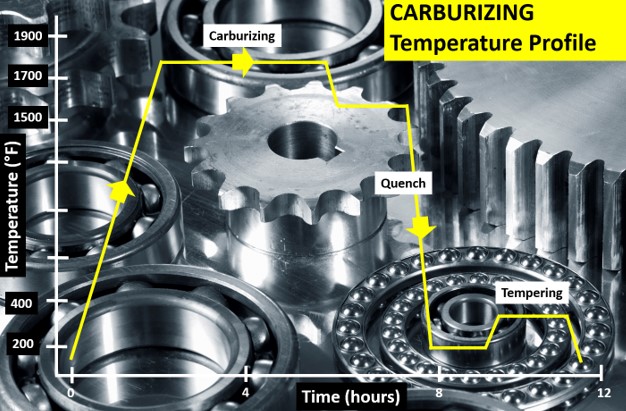

Carburizing has rapidly become one of the most critical heat treatment processes employed in the manufacture of automotive components. Also referred to as case hardening, it provides necessary surface resistance to wear, while maintaining toughness and core strength essential for hardworking automotive parts.

The carburizing process is achieved by heat treating the product in a carbon rich environment (Figure 1), typically at a temperature of 1562°F–1922°F (850°C–1050°C). The temperature and process time significantly influence the depth of carbon diffusion and other related surface characteristics. Critical to the process is a rapid quenching of the product following the diffusion in which the temperature is rapidly decreased to generate the microstructure, giving the enhanced surface hardness while maintaining a soft and tough product core.

The outer surface becomes hard via the transformation from austenite to martensite while the core remains soft and tough as a ferritic and/or pearlitic microstructure. Normally, carburized microstructures following quench are further tempered at temperatures of about 356°F (180°C) to transform some of the brittle martensite into tempered martensite to enhance ductility and grindability.

Critical Process Temperature Control

As discussed, the success of carburization is dependent on accurate, repeatable control of the product temperature and time at that temperature through the complete heat treatment process. Important to the whole operation is the quench, in which the rate of cooling (product temperature change) is critical to achieve the desired changes in microstructure, creating the surface hardness. It is interesting that the success of the whole heat treat process can rest on a process step which is so short (minutes), in terms of the complete heat teat process (hours). Getting the quench correct is not only essential to achieve the desired metal microstructure, but also to ensure that the physical dimensions and shape of the product are maintained (no distortion/warping) and issues such as quench cracking are eliminated.

Obviously, as the quench is so critical to the whole heat treat process, the correct quench selection needs to be made to achieve the optimum properties with acceptable levels of dimensional change. Many different quenchants can be applied with differing quenching performances. The rate of heat transfer (quench rate) of quench media in general follows this order from slowest to quickest: air, salt, polymer, oil, caustic, and water.

Technology Challenges for Temperature Monitoring

When considering carburization from an industry standpoint, furnace heat treat technology generally falls into one of two camps, embracing either air quench (low pressure carburization) or oil quench (sealed gas carburization/LPC with integral or vacuum oil quench). Although each achieves the same end goal, the heat treat mechanisms and technologies employed are very different, as are the temperature monitoring challenges.

To achieve the desired carburized product, it is necessary to control and hence monitor the product temperature through the three phases of the heat treat process. Conventionally, product temperature monitoring would be attempted using the traditional trailing thermocouple method. For many modern heat treat processes including carburization, the trailing thermocouple method is difficult and often practically impossible.1 The movement of the product or product basket from stage to stage, often from one independent sealed chamber to another (lateral or vertical movement), makes the monitoring of the complete process a significant challenge.

With the industry driving toward fully automated manufacturing, furnace manufacturers are now offering the complete package with full robotic product loading that includes shuttle transfer systems and modular heat treat phases to process both complete product baskets and single piece operations. Although trailing thermocouples may allow individual stages in the process to be measured, they cannot provide monitoring of the complete heat treat journey. Testing is therefore not under true normal production conditions, and therefore is not an accurate record of what happens in normal day to day operation.

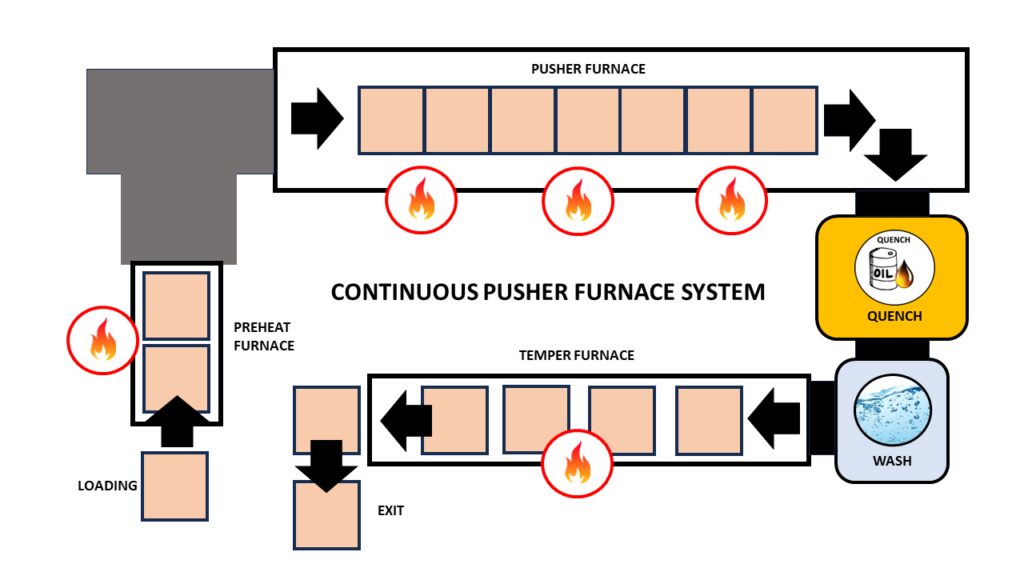

Figure 2 shows schematic diagrams of two typical carburizing furnace configurations that would not be possible to monitor using trailing thermocouples. The first shows a modular batch furnace system where the product basket is transferred between each static heat treat operation (preheat, carburizing furnace, cooling station, quench, quench wash, temper furnace) via a charge transfer cart. The second shows the same heat treat operation but performed in a continuous indexed pusher furnace configuration where the product basket moves sequentially through each heat treat operation in a semi-continuous flow.

Thru-process temperature monitoring as a technique overcomes such technical restrictions. The data logger is protected by a specially designed thermal barrier, therefore, can travel with the product through each stage of the process measuring the product/process temperature with short, localized thermocouples that will not hinder travel. The careful design and construction of the monitoring system is important to address the specific challenges that different heat treat technology brings including modular batch and continuous pusher furnace designs (Figure 2).2

The following section will focus specifically on monitoring challenges of the sealed gas carburizing process with integral oil quench. Technical challenges of the alternative low pressure carburizing technology with high pressure gas quench have previously been discussed in an earlier publication.3

Monitoring Challenges of Sealed Gas Carburization — Oil Quench

Presently, the most common traditional method of gas carburizing for automotive steels is often referred to as sealed gas carburizing. In this method, the parts are surrounded by an endothermic gas atmosphere. Carbon is generated by the Boudouard reaction during the carburization process, typically at 1562°F–1832°F (850°C –1000°C). Despite the dramatic appearance of a sealed gas carburizing furnace, with its characteristic belching flames (Figure 3), from a monitoring perspective, the most challenging aspect of the process is not the heating, but the oil quench cooling. For such furnace technology, the historic limitation of “thru-process” temperature profiling has been the need to bypass the oil quench and wash stations, missing a critical process step from the monitoring operation. Obviously, passing a conventional hot barrier through an oil quench creates potential risk of both system damage from oil ingress and barrier distortion, as well as general process safety. However, the need to bypass the quench in certain furnace configurations by removing the hot system from the confined furnace space could create significant operational challenges, from an access and safety perspective.

Monitoring of the quench is important as ageing of the oil results in decomposition (thermal cracking), oxidation, and contamination (e.g. water) of the oil, all of which degrade the viscosity, heat transfer characteristics, and quench efficiency. Control of physical oil temperature and agitation rates is also key to oil quench performance. Quench monitoring allows economic oil replacement schedules to be set, without risk to process performance and product quality.

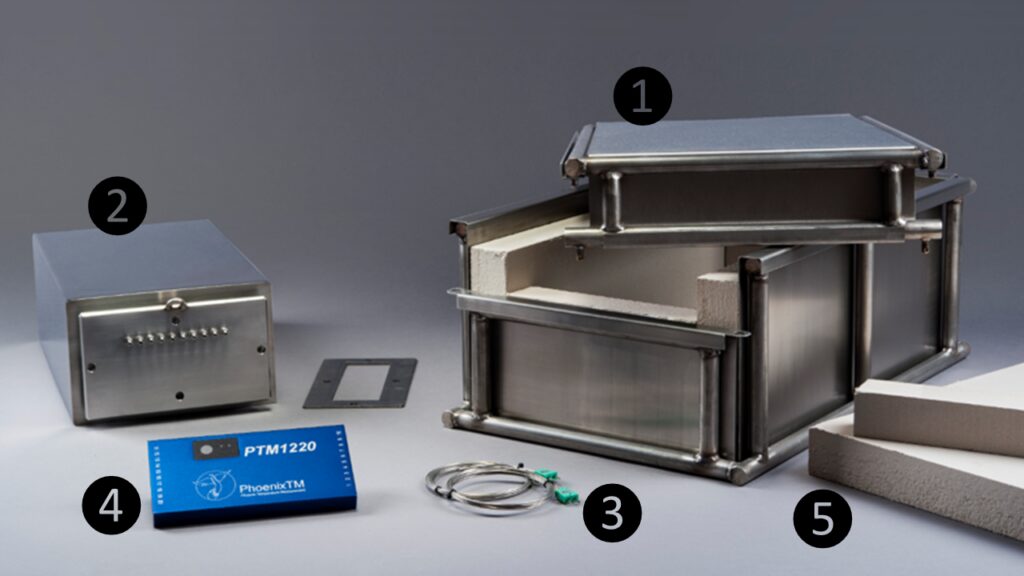

To address the process challenges, a unique thermal barrier design has been developed that both protects the data logger in the furnace (typically three hours at 1697°F/925°C) and also protects during transfer through the oil quench (typically 15 mins) and final wash station (Figure 3). The key to the barrier design is the encasement of a sealed inner barrier with its own thermal protection with blocks of high-grade sacrificial insulation contained in a robust outer structural frame (Figure 4).

Quench Cooling Phases

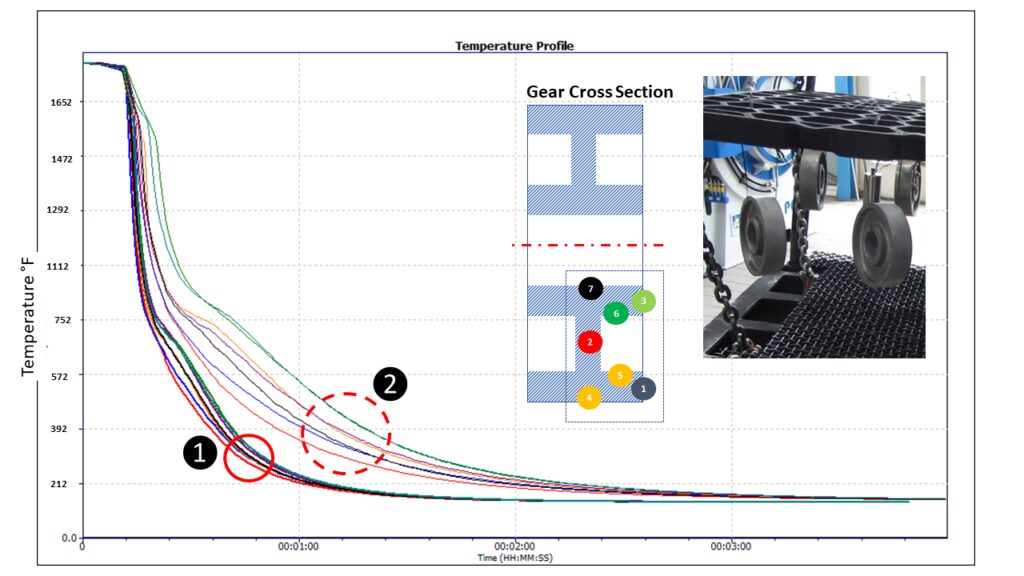

Monitoring the oil quench in carburization gives the operator a unique insight into the product’s specific cooling characteristics, which can be critical to allow optimal product loading and process understanding and optimization. From a scientific perspective, the quench temperature profile trace, although only a couple of minutes in duration, is complex and unique. From a zoomed in quench trace (Figure 5) taken from a complete carburizing profile run, the three unique heat transfer phases making up the oil quench cool curve can be clearly identified:

- Film boiling “vapor Blanket”: The oil quenchant creates a layer of vapor (Leidenfrost phenomenon) covering the metal surface. Cooling in this stage is a function of conduction through the vapor envelope. Slow cool rate since the vapor blanket acts as an insulator.

- Nucleate boiling: As the part cools, the vapor blanket collapses and nucleate boiling results. Heat transfer is fastest during this phase, typically two orders of magnitude higher than in film boiling.

- Convective heat transfer: When the part temperature drops below the oil boiling point. the cooling rate slows significantly. The cooling rate is exponentially dependent on the oil’s viscosity.

From a heat treat perspective, the quench step relative to the whole process (hours) is quick (seconds), but it is probably the most critical to the performance of the metallurgical phase transitions and achieving the desired core microstructure of the product without risk of distortion. By being able to monitor the quench step, the process can be validated for different products with differing size, form, and thermal mass. As shown in Figure 6, the quench curve profile over the three heat transfer phases is very different for two different automotive gear sizes.

Summary

As discussed in this article, one of the key process performance factors associated with gas carburization is the control and monitoring of the product quench step. Employing an oil quench, the measurement of such operation is now very feasible as part of heat treat monitoring. Innovations in thru-process temperature profiling technology offer specific system designs to meet the respective application challenges.

References

[1] Dr. Steve Offley, “The light at the end of the tunnel – Monitoring Mesh Belt Furnaces,” Heat Treat Today, February 2022, https://www.heattreattoday.com/processes/brazing/brazing-technical-content/the-light-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel-monitoring-mesh-belt-furnaces/.

[2] Michael Mouilleseaux, “Heat Treat Radio #102: Lunch & Learn, Batch IQ Vs. Continuous Pusher, Part 1,” interviewed by Doug Glenn, Heat Treat Radio, October 26, 2023, audio, https://www.heattreattoday.com/media-category/heat-treat-radio/heat-treat-radio-102-102-lunch-learn-batch-iq-vs-continuous-pusher-part-1/.

[3] Dr. Steve Offley, “Discover the DNA of Automotive Heat Treat: Thru-process Temperature Monitoring,” Heat Treat Today, August 2023, https://www.heattreattoday.com/discover-the-dna-of-automotive-heat-treat-thru-process-temperature-monitoring/.

About the Author

Dr. Steve Offley, “Dr. O,” has been the product marketing manager at PhoenixTM for the last five years after a career of over 25 years in temperature monitoring focusing on the heat treatment, paint, and general manufacturing industries. A key aspect of his role is the product management of the innovative PhoenixTM range of thru-process temperature and optical profiling and TUS monitoring system solutions.

For more information: Contact Steve at Steve.Offley@phoenixtm.com.