Heat Treat Radio #129: Understanding US Energy Initiatives and Their Impact on Heat Treating

In this episode of Heat Treat Radio, Doug Glenn sits down with Michael Mouilleseaux of Erie Steel Treating to examine U.S. energy initiatives and their implications for the heat treating industry. Mouilleseaux, who also chairs the Metal Treating Institute Regulatory Task Force, provides context on energy costs, emissions data, and the practical challenges associated with electrification and alternative fuels in industrial heating. The discussion explores how policy decisions affect energy reliability and day-to-day manufacturing operations, and whether current approaches align with the operational realities of heat treating.

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Introduction

Doug Glenn: Today, we are welcoming back a guest that we’ve had on Heat Treat Radio several times: Michael Mouilleseaux from Erie Steel Treating in the Toledo, Ohio area. We are going to be discussing energy policies that are impacting captive heat treaters, commercial heat treaters, heat treating industry suppliers, all of those folks — should be a pretty interesting conversation.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions By the Numbers (2:00)

Doug Glenn: Michael has some pretty interesting statistics about pollution, sustainability, and energy. Could you share some of those stats with us?

Michael Mouilleseaux: The United States represents about 11% of the total greenhouse gas emissions — total. China represents 30%. India is almost equivalent with us. They are just under 10%. 2007 is said to be the peak year for greenhouse has emissions worldwide. Since 2007, the U.S. has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions 15%. During that time, we have increased our energy production by 45%. Obviously, we’re doing something right.

In that same timeframe, the rest of the world has increased their greenhouse gas emissions 20%. When we talk about what is it that the U.S. is doing and what more do we need to be doing — we are doing more than anyone else.

In the U.S., what are the component parts of these greenhouse gas emissions? They are transportation, electric generation, and industry, and they are all about 25% or 30%.

Heat treating as a small part of industry represents 0.3% of the U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Doug Glenn: Is that across all of the component parts?

Michael Mouilleseaux: That is across everything, 0.3%. And yet, we are going to have the conversation, “Why us?”

Fuel Costs (4:07)

Michael Mouilleseaux: In the U.S., natural gas costs less than $3 per million BTU. In Germany, it’s $12 per million BTU.

Doug Glenn: Which is four times the rate.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Correct, four times the rate. Now, there was a time in the U.S. when gas was that expensive, and I remember that. That was not a fun time to be in the heat treating industry.

When we say gas cost $3 million BTU and $12 million BTU, that’s the commodity cost — that doesn’t include transportation. Electricity in the U.S. for industrial customers averages a little over 8 cents a kilowatt hour. Germany is the largest economy in the European Union. In Germany, electricty costs over 30 cents a kilowatt hour.

A couple of interesting facts as we talk about what the legislation is and how it affects us: 40% of the U.S. Congress members are lawyers. Less than 2% of the members are engineers. Here, we have this highly technical discussion about clean air, thermodynamics, and these models that are used to generate the information that the industry is being held accountable for. Yet less than 2% of the members of Congress even understand it.

So how did this whole thing get started? It goes back to the Clean Air Act of 1970, which was a national air quality standard that named six pollutants and covered the United States only. We’re going to come back to this point because it’s significant.

In 1990, the Clean Air Act was amended by Congress, and now included 180 pollutants.

Doug Glenn: So it went from 6 to 180 pollutants.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Do we remember what the seventies were like? If you do, you can remember seeing televisions shots of Southern California — you could not see anything because the smog was so bad. So, was this legislation justified? I would say that it absolutely was.

Doug Glenn: That and the Cuyahoga River being on fire.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Exactly, so it was very important. MTI has this initiative in California. Why have we focused on a single state? It was the clean air acts in California in the 1960s that spurred the U.S. Congress to generate the Clean Air Act, which now has nationwide application.

Doug Glenn: I’ve heard it said that what starts in California spreads to the rest of the nation and the rest of the world.

Michael Mouilleseaux: It absolutely does. So we have the Clean Air Act. Secondly, in 2007 — we have gone from 1970 to 2007 — the Obama Administration made decisions based on two pieces of information: a Supreme Court ruling, and information that was generated by what’s called the IPCC, which is the Intergovernmental Climate Change Panel.

Doug Glenn: Okay.

Michael Mouilleseaux: In this panel — a highly politicized body, by the way — they came up with the information that said that with a certain amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, the earth is going to heat up. If it heats up, the solar ice caps will melt. Sea levels will rise, we are going to have monsoons. A very catastrophic scenario was presented by this panel.

Based upon that, the Obama Administration EPA had what they called an endangerment finding. Endangerment is not a scientific term, it’s non-engineering term. It’s a legal term. It means risk of harm, not actual harm, but a risk of harm. The EPA took this information and said there’s a risk of harm to the U.S. population, and as a result of that, we are going to implement legislation.

The first legislation that came down the pike was the Clean Power Plan Act. EPA mandated that the states had to regulate the CO2 emissions of the power plants. At that time, the regulation mandated that by 2030, the greenhouse gas emissions had to be reduced 30%. That’s 23 years from 2007 to 2030. It seems almost reasonable.

Doug Glenn: Just to be clear, they said you need to reduce it by 30%, not to 30%. In other words, you don’t need a 70% reduction, you just need to reduce it 30%.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Correct.

Now we fast forward to 2021, and the Biden Administration comes in, it’s difficult to describe this and not sound political, but the years are what they are, and the people that were in power are who they were — this is the result of that. In 2021, just as Biden comes into office, he issues an executive order mandating a clean energy economy.

He charged the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy to develop a plan to further the reduction in greenhouse gases. In effect, it affected all three segments of the U.S. economy that generate greenhouse gases. With the previous Power Plant Act, greenhouse gases had to be reduced 30% by 2030. Under the Biden Administration, that regulation was changed to an 85% reduction, and you had to have net zero emissions by 2050.

This applied to the power plants. It applied to automobiles, the transportation sector. That’s where you saw all of these incentives that are in place. There was a huge push for electric cars. If you recall, 40% of the vehicles sold by 2030 were to have been electric vehicles, and by 2050, it was supposed to be an all-electric economy. Same thought process going into play there as it applies to the industrial sector.

There were five segments of the industrial sector: iron and steel, manufacturing, chemical processing, petroleum processing, and food and beverage. All five of these segments of the industrial sector were subject to the same mandate. Thatis, that by 2030, an 85% reduction in greenhouse hases and net zero by 2050.

Four Pillars of Mitigation (13:09)

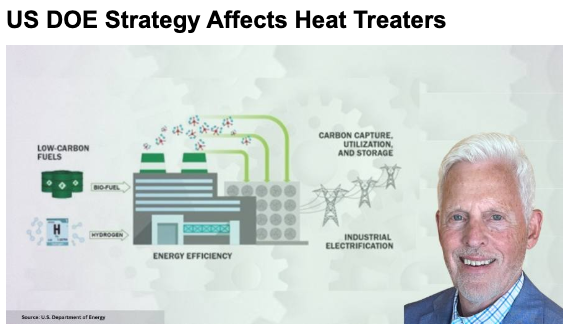

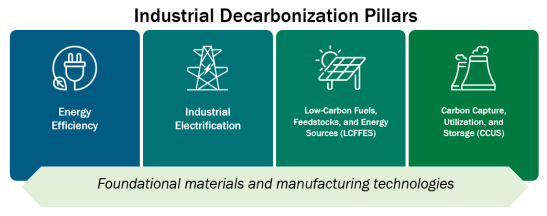

Michael Mouilleseaux: That administration came up with what they call the Four Pillars of Mitigation. The pillars of mitigation were energy efficiency, the use of low carbon fuels, carbon caption, and electrification.

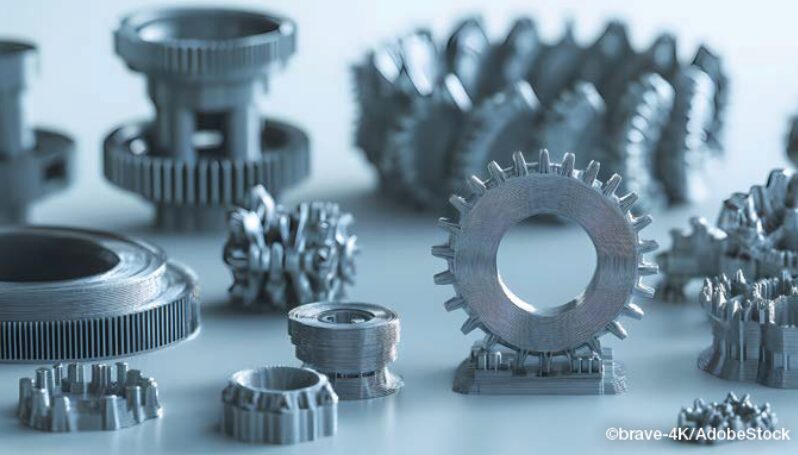

We ask then, “Why heat treating?” As we mentioned, it’s only 0.3% of greenhouse gas emissions across the five target areas. Where did heat treating come into play? Well, there was a symposium held by the Department of Energy in the summer of 2023. In that symposium, they further defined the segments within these five areas that I spoke of, and in the iron and steel industry, they made the determination that 63% of the energy that’s used in the iron and steel industry is in process heating. Then they further segmented it, and they said heat treating is a significant sector in process heating.

So almost as an afterthought, heat treating got pulled into this.

Doug Glenn: Quick clarification question on that. When they talk about process heating and the iron steel, are they talking about steel making or everything downstream from it?

Michael Mouilleseaux: Both.

Doug Glenn: Okay, alright.

Michael Mouilleseaux: It’s all inclusive.

Pillar One: Energy Efficiency (14:46)

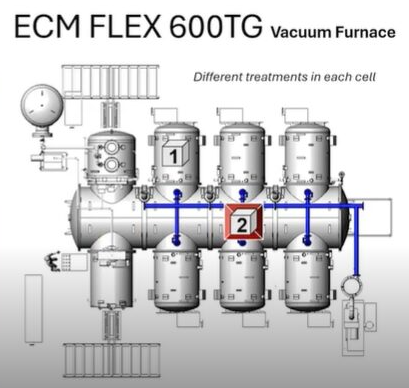

Michael Mouilleseaux: How do the mitigating pillars apply to heat treating? Let’s look at energy efficiency. I had a conversation with several furnace manufacturers and my question to them was, “if we looked at equipment that’s 20 or 25 years old and compared it today, how much more efficient is the equipment today?” We are talking state-of-the-art equipment. How much more efficient is that equipment than what we had that’s 20 years old? The answer is that the maximum would be 20%.

Doug Glenn: 20% more efficient.

Michael Mouilleseaux: 20% more efficient at maximum, not average. That’s the absolute maximum. So we’re not going to get our 85% reduction in greenhouse gases by a 20% improvement in efficiency.

Pillar Two: Low Carbon Fuels (15:40)

Michael Mouilleseaux: The next element was low carbon fuels.

Doug Glenn: That’s pillar number two.

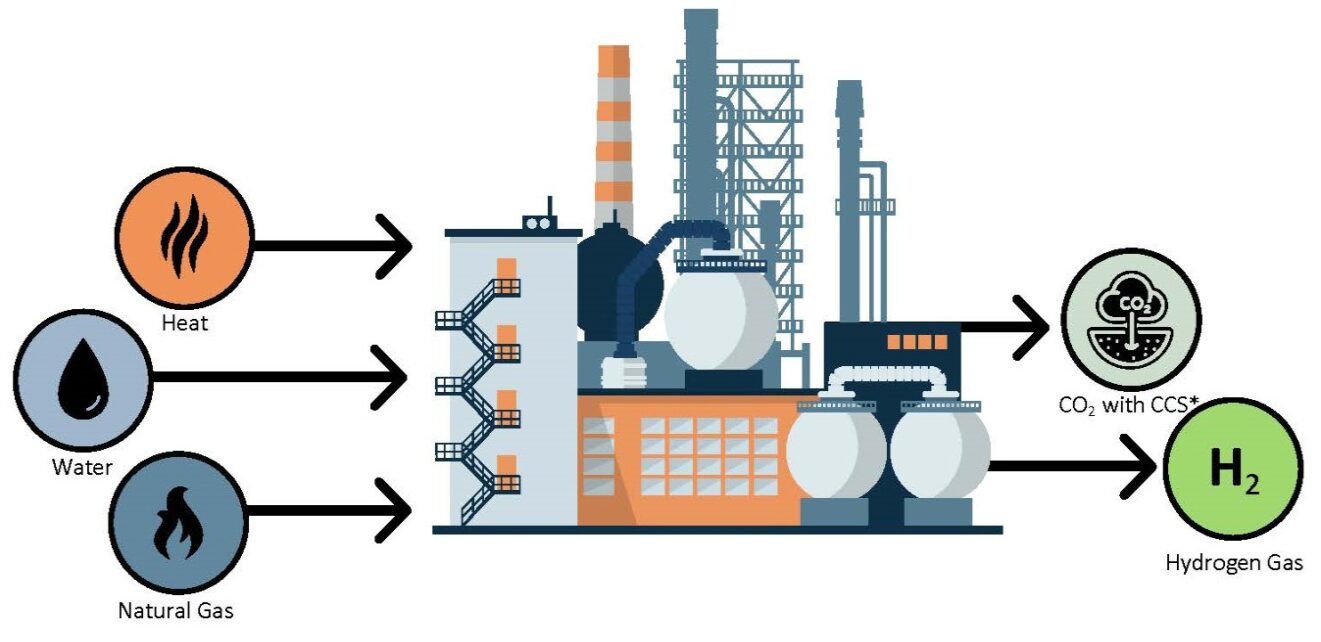

Michael Mouilleseaux: Pillar number two. After you make your way through what they were talking about — and there’s some discussion about biofuels and things of that nature — at the end of the day, it’s all about hydrogen. Their goal was to utilize hydrogen in place of natural gas as fuel source. Is that technically feasible? The answer to that is yes. Where you run into the problem is how practical is it?

Firstly, is there a distribution center, a methodology for hydrogen? Could you just put it in in the natural gas pipelines and use it? Not as they’re currently configured; it would require some work.

Secondly, how are you going to generate all of this hydrogen? Today the way that hydrogen is generated is a method called steam methane reform in which you take methane, which is natural gas, and you heat it by using natural gas, and then you inject steam. In doing so, you strip away the hydrogen. Steam H2O and you strip away the hydrogen from the oxygen. The oxygen you can put back in the atmosphere, and the hydrogen you capture and that’s what you’re going to sell.

The cost of that today is about $15 per million BTUs.

Doug Glenn: Regular natural gas we said was less $3 per million BTUs. So it’s a five times increase in cost.

Michael Mouilleseaux: There we go. Now the other thing is you are using 2.5 million BTUs of methane or natural gas to make 1 million BTUs of hydrogen. So, if you’re not an engineer, you are just fine with that. But to those of us that that can do a little bit more than just add and subtract, it makes no sense. It’s nonsensical.

In addition, there are no facilities that could generate the amount of hydrogen that we’d be needed to supply industry.

Doug Glenn: You’re using two times the fuel to make it, but also, doesn’t hydrogen have like a quarter of the BTUs of natural gas?

Michael Mouilleseaux: There we go. Now the other thing is you are using 2.5 million BTUs of methane or natural gas to make 1 million BTUs of hydrogen. So, if you’re not an engineer, you are just fine with that. But to those of us that can do a little bit more than just add and subtract, it makes no sense. It’s nonsensical.

In addition, there are no facilities that could generate the amount of hydrogen that we’d be needed to supply industry.

Doug Glenn: You’re using two times the fuel to make it, but also, doesn’t hydrogen have like a quarter of the BTUs of natural gas?

Michael Mouilleseaux: There is another way of generating hydrogen, and that is electrolysis. You take water with a sufficient amount of electrical input. You can strip the hydrogen off the oxygen, you can use a membrane sieve, you can separate them out. This is a well-known, well-established method that has been done for quite a long time.

Two considerations with this method. Firstly, where does the electricity that you use come from? In this country today, 40% of our electricity is generated from natural gas. So if you are going to say that we are going to reduce the CO2 output and you’re utilizing natural gas to generate electricity, there is an issue there. The second consideration is the cost. The cost today of electrolysis-generated hydrogen is about $60 per million BTUs.

Doug Glenn: In summary, it’s $3 per million BTUs for natural gas, $15 per million BTUs for methane separated, and $60 per million BTUs for electrolysis separated.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Correct, that’s today. The industrial roadmap that the Biden Administration came up with determined we would use green energy — wind turbines and solar panels. We all know that those energy sources are free because the wind blows for nothing and the sunlight comes out and graces us with its presence every day. The administration wanted to get a million BTUs of hydrogen, and the cost of that to be half of what the current cost of natural gas is.

Doug Glenn: Which would mean about a dollar and a half.

Michael Mouilleseaux: If that isn’t irrational exuberance, I don’t know what is.

Doug Glenn: You’re right.

Pillar Three: Carbon Capture (21:16)

Michael Mouilleseaux: The third pillar is carbon capture. Carbon capture is a technology where you would take the CO2 that’s emitted from a combustion process or other processes, and in utilizing molecular sieves and such, you would trap that. Sometimes they will generate dry ice out of it. Other times, you might just inject it into the into the crust of the earth. Today there are 54 carbon capture operations operating worldwide. Worldwide. In the United States, it’s less than 10. All of these things have to do with petroleum processing. They’re taking natural gas wells, let’s say, and burn the natural gas. This will generate the energy that can be used to generate these sequestration efforts. That’s how it’s paid for.

There is nothing available today on a level that you would be using in a heat treating operation. The carbon capture plants take up acres. This is not a small confined operation.

Doug Glenn: So once again, doable but not practical.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Correct.

Pillar Four: Electrification (22:57)

Michael Mouilleseaux: The last pillar is electrification. We all know there are electric furnaces today. We have had many presentations by furnace manufacturers over the years. Most recent that I have seen is that an electric furnace equivalent to a gas fired furnace probably costs 10% less.

You might make the case that the maintenance on that would be less because you don’t have as many moving parts and gas trains, etc. But the operating cost might be three or four times what the operating cost is for a gas-fired furnace. As such, it’s an economic issue.

Doug Glenn: Why do we say three to four times the cost? Is that based on the cost of electricity?

Michael Mouilleseaux: The cost of electricity, yes. It’s three or four times as much. We talked about the fact that the average cost of industrial electricity is around 8.5 cents in the U.S. It varies from 5 to 25 cents. We are just looking at the average.

In addition, if you take all of the gas-fired equipment in this country and power it with electricity, how much would you need? The answer to that is that you would need a significant amount, and we do not have that amount of electricity available.

Doug Glenn: Considering that the hot topic of the day is the data processing centers, they are going to be sucking up a lot more electricity than we have even now. So it’s not like the electricity is going to be readily available within the next five years or so.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Precisely. You look at these data processing centers and predominantly they are using natural gas-fired turbines to generate the electricity for them. Many of them have their own power plants. They have micro grids. There are two or three of them that have made applications to the NRC to use small modular nuclear reactors. These individuals are from Silicon Valley who typically have been green. Yet they recognize that green is not going to be the key to success.

Even in their case, the practicalities of dependable cost-effective power trumps the need to be green or at least appear to be compliant with all of our climate requirements.

Effects on the Industry (26:06)

Michael Mouilleseaux: What are the effects that these initiatives have on industry? If you think about what we’ve discussed so far, we are talking about destabilizing our industry, as a result of trying to use unproven technologies. Other than electric-powered furnaces, none of these methods currently exist today, either on a scale or are cost effective, that we could use to replace the power that we use in the heat treating industry.

So when we say a five times or a twenty times increase in cost, power is typically about 10% of the cost of a heat treating operation.

Those numbers come from an annual MTI survey. We talk about what costs are involved in the heat treating operation and power is always the second or third cost. From the MTI survey, it averages 10%.

If I have a captive operation, it’s different. I happened to have some experience in the captive industry. I ran what was arguably the largest captive heat treating operation in North America, in Syracuse, New York. We had 15 multi roll pushers. To those people, would it matter if the cost of energy went up five times or more? It absolutely would. Power was a huge concern and we made many efforts in attempts to reduce the amount of power that we needed to do.

Doug Glenn: You were probably happy if you could get it down a percent or two.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Yes, and that was one of those installations where efficiency was the way that we went about doing that. When you have a heat treating operation that’s supporting a large manufacturing operation, the heat training operation is never the pinch point in getting out production. It’s always the manufacturing operations. We ran extremely inefficiently to support those operations.

We talked about destabilizing these things. The implementation schedule that we’re talking about is unrealistic — achieving an 85% reduction in greenhouse gas in 10 years and none of these technologies that we’ve talked about is going to achieve that.

It’s destabilizing because it’s unproven, it’s destabilizing because the implementation schedule is unrealistic, and it’s destabilizing because of the increase in cost.

Doug Glenn: There are some who have done this, like in Europe, for example. I believe they have moved in this direction. You were talking about the price of energy over there. What about their efforts?

Michael Mouilleseaux: I’m going to reference Germany, because Germany is 25 or 30% of the European economy. We know that their electric power is four times what it is here. We know that gas is similar. German industry is an absolute powerhouse, or at least it had been.

In recent years, subsequent to the pandemic, their economy went down. They recovered, and since then they have lost industrial output 2% to 3% per year. Right now they are 10% below where they were.

Doug Glenn: Where they were at the bottom of the pandemic?

Michael Mouilleseaux: Not at the bottom, prior to the pandemic. What are the reasons for that? In Germany, do they make the best cars? They certainly think they do. Do they have the best machine tools? They definitely think that they do. Do they have the best chemical processing plants? They definitely think that they do. I know for a fact that BASF, which is a large German chemical processing business, the last two chemical processing plants that they built were in Louisiana, and I don’t believe Louisiana is within the German Democratic Republic.

When you look at that, the German Central Bank, the European Central Bank have all taken a look at these changes. They issue annual reports on the various members of the EU, and every report that has come out in the last three to four years has specifically stated that it’s the high cost of regulation and it’s the high cost of energy that has been the cause for the diminishment in German industrial output.

Doug Glenn: That’s very interesting.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Additionally, when we talk about renewables, you have to understand that there’s a risk of interruption of service. How many interruptions or blackouts have there been in California? We really don’t hear of them in this part of the country because it really doesn’t affect us. But I believe that the number of blackouts in California last year exceeded 100. W do not know the length of these blackouts, but when you have an industrial process that’s going on, it doesn’t take much of an interruption to where everything has to be reset. The potential to have damaged equipment, certainly damaged product, that has to be taken into consideration.

Let’s also consider Portugal, another European country. I believe that 70% of Portugal’s energy is generated by wind power. Earlier this year, Portugal had a two-day blackout nationwide, and it all had to do with the fact that the power is generated by a wind turbine. Neither wind turbines nor solar panels generate alternating current. They all generate direct current. You have to put it through an inverter and it has to be cleaned up. Here in the U.S. we have 60 cycles per minute. This is our alternating current. In Europe, it’s 50 cycles. There’s not a tremendous amount of variability that’s allowed in that. So when things become off cycle, it shuts down the entire grid, and that’s essentially what happened in Portugal. It took them two days to restart the country.

Consequently, there’s a cost there. I understand what the goal is. I’m just questioning the methodology and how you get there.

Doug Glenn: And the practicality, once again, the practicality of it. If Europe is teaching us anything, they’re showing us the outcomes, whether intended or unintended, of moving in that direction.

Michael Mouilleseaux: In all fairness, it’s moving in that direction too quickly. I don’t think that there are any of us who say that this goal is not admirable or that it’s not something that we want to accomplish. The question becomes how do you go about doing that?

Doug Glenn: Thinking about what’s going on nowadays, there may be different reasons why they’re moving too quickly. I could see in Europe, especially Eastern Europe, why they may be moving quickly away from gas with the whole Russia and Ukraine conflict and the fact that they get most of their gas from there. I can see that and that I would consider to be somewhat of a market effect, even though it’s based on war. It’s not something that was imposed by authorities. It’s an outcome of an event.

You can see why they’d be moving quickly that way. The rest of the country, and the fact that we’re trying to convert so quickly to electricity is self-inflicted by regulation primarily.

Recent Changes in the States (36:00)

Doug Glenn: I know there’s some changes here recently in the states. Can you discuss those?

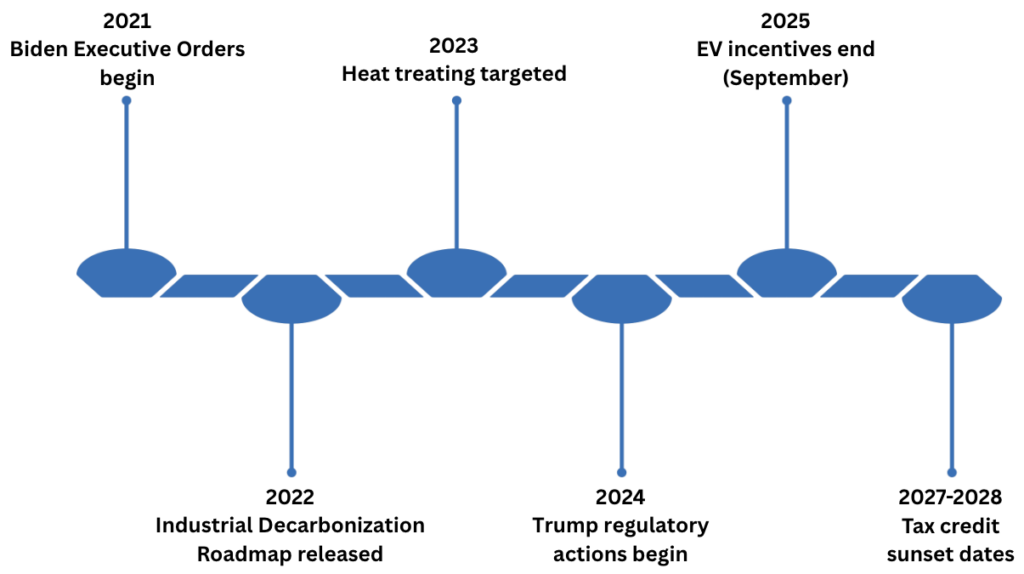

Michael Mouilleseaux: Almost every initiative and mandate that we have mentioned that happened during the Biden Administration was achieved via executive order. When it comes to executive orders, they can be overturned when you are no longer in office.

I recently looked at a paper that was done by the Institute for Energy Research, and they said that the Trump Administration, through September, had 20 regulatory actions or executive orders that were related to energy production.

Most of them overcame, overturned, rescinded what was in that industrial decarbonization roadmap. There were a couple of initiatives that were actually codified during the Biden administration. Those were codified in the IRA, the Inflation Reduction Act. In the IRA, they implemented an investment tax credit and a production tax credit concerning renewable energy. The investment tax credit relative to renewable energy gave you a 30% tax break on all investments that were in renewable energy, and the production tax credit gave you a credit for every kilowatt hour of energy that you produced.

If I have a wind turbine that’s generating 200,000 kilowatts, and I’m getting back from the government 3 or 4 cents, and I’ve purchased that equipment at 70% of what it costs, all of a sudden I have the ability to undercut what the current power plants are asking for for the power that they’re generating.

First of all, this is a tremendous displacement of capital. People are going to say, where am I going to put my money? If I put it into this and I’m buying it for 70 cents on the dollar, that’s a pretty good investment and I’m guaranteed that I’m going to get so much money from the federal government for the energy that I generate.

Doug Glenn: This is not the excess energy that you produce. It could be energy that you produce and you use. You’re getting paid by the government to produce your own energy.

Michael Mouilleseaux: This is on an industrial scale. The huge wind farms that you see — they are put in place simply to sell energy to the grid.

The other consequence is that when they are generating electricity, the base load plants using natural gas, they’re not able to sell their power. They have to curtail or shut down. The issue becomes when the wind stops blowing, or the sun is not out, where does that energy come from?

Doug Glenn: The base load.

Michael Mouilleseaux: It has to come from those base load plants. These plants are typically going to run for 80% of the time. If I can run 80% of the time, I know that I can generate this amount of power. I have these costs and this is what we’re going to sell it for. Now all of a sudden, if you’re telling me that I have to do it for 20% of the time, the cost structure changes.

These are all public utilities that are regulated not just federally, but in each state. The regulations are onerous and difficult to understand.

One of the things that you see is that for those of us that purchase power for industrial use, the peak cost of electricity has risen dramatically. The reason for that is they have to have some way that they can recapture these costs.

Doug Glenn: And make up for the fact that they’re not producing the same amount of electricity all the time.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Right. Going back to the investment tax credit and the production tax credit. The big, beautiful bill that was H.R. 1 that was signed on July 4, rescinded these tax credits. It didn’t rescind them immediately though. Most of the rescission takes place in 2027 and 2028. One of the things the Democrats did that was very smart is that they made sure that most, if not many of these renewable energy installations were done in red states. So if you’re going to rescind these acts, it’s going to be very difficult and painful politically for the red state politicians to do that. As a result of that, they didn’t end the credits immediately. They pushed it out.

The incentives for electric cars ended at the end of September 2025. It will be interesting to see what’s going on there. The Europeans have some experience with that. The Germans ended their tax credit and they cut the electric car market in half.

Doug Glenn: We know Elon Musk was not very happy about that.

Michael Mouilleseaux: The investment tax credit and the production tax credit were sunsetted in 2028. But by executive order, the bill did something else — it changed the eligibility requirements for the credits. Previously, under the prior administration, if you had 5% of a project completed, then you were eligible to receive these tax credits. You could have a plan and you could have a place that you wanted to do it. But you did not even need to have purchased the land, you did not need to have purchased the equipment. You just had to have a good idea and you were going to get money for it.

This changed to where the project had to be 20% completed. So now you have to have purchased land. You have to know where you are going to put it. You have to have contracts for equipment. Although the bill didn’t achieve exactly what we were hoping to see, it was successful in that regard.

The last thing this current administration has done, and it may well end up being the most significant, is that the EPA has made a plan to rescind the 2000 endangerment finding.

As we mentioned, the endangerment finding identified greenhouse gases. The original charter of the EPA named 6 pollutants, and this 2007 endangerment finding identified greenhouse gases and specifically CO2 as a pollutant. The reason that I mentioned that the original finding applied to the continental United States is that this finding, the 2007 finding, references global warming, global climate change. One of the things that they are going to use to attempt to overturn this is on the basis that the EPA has simply overreached the original charter.

It’s complicated. In 2014, the activist Supreme Court that we had at that time, did find that it was within the purview of the EPA to control greenhouse gases. On that basis, they said, we have a green light and this is what we’re going to do, and you can see what’s transpired. There was a finding by this current Supreme Court, and it was called the Major Questions Doctrine. And the Major Questions Doctrine says that a regulatory agency cannot dictate policy above and beyond what is in their original charter.

When I said that they are going to go after this agency on the basis that they’re claiming that CO2 should be controlled because it leads to global warming, that is not in the original charter. The original charter says only what happens within the United States.

In addition, the science that was used in the original 2007 endangerment finding was reviewed by this international organization, the IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate. This pane did not have singular findings. They had groups of findings. It was science based upon scientific models. The panel said, if this happens, then it would lead to this amount of increase in temperature. If that happens, it could lead to this. There were scenarios within that were many and varied.

The Obama Administration chose not the average scenario, but the worst case scenario. Based upon the worst case, this has been done. The current administration is reviewing that science and they’re saying that there is evidence now that the models that you used did not come to fruition. That’s pretty condemning evidence in and of itself. There’s also new evidence that says that we do not have anywhere near the issue that previously thought. One thing that was never taken into consideration is the resilience of people. For example, if there’s an increase in sea level, maybe people move to higher ground.

There were so many perspectives that were never taken into consideration and we can now see how people react to their environment. That it is nowhere near the difficulty that we thought.

Doug Glenn: We are not going to stand on the seashore and drown as the water creeps up over our nose in over a five-year span. We are going to move.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Having said that, this rescission process is going to take two or three years. The environmental industrial complex is going to do everything within their power to make sure that legally that this doesn’t go through.

The environmental industrial complex is a 100 billion dollar industry composed of thousands of NGOs that are interlocked, intertwined, and there are a hundred thousand people that are involved in this. This is not just the guy on the street corner with a sign that says “save the planet.” This is an industry and it has all of the machinations that would go on, and their self-preservation is number one.

Doug Glenn: They are going to do all they can to maintain the level of crisis in order to keep their business afloat.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Right. If this effort is successful, this will change forever what the EPA will and will not be able to.

It’s very important. As consumers and members of this republic, it’s incumbent upon us to make sure that our representatives support this effort so that they know that, although they are up against a significant foe here, they have the support of the people.

What Can We Change in the Short Term? (50:55)

Doug Glenn: Any concept of what we need to do in the short term, over the next couple years or so?

Michael Mouilleseaux: I think that we really need to recodify the EPA charter. If this endangerment finding is overturned, that is one way that this situation could be turned around. The other would be if Congress were to revisit what the mandate for the EPA is and state it in legislation, because if it were stated in legislation, then this this finding is of no consequence at all.

Of course, the difficulty there is that you may get through the house, but you do not have a filibuster-proof Senate. That’s obviously the challenge that we face on this.

Is There a Rational Policy for Transitioning to Non-Fossil Fuels? (51:49)

Michael Mouilleseaux: Is there a rational policy for transitioning to non-fossil fuels? First of all, it’s not a question of should we do this. Global warming is a fact; there’s no denying it. The effects of global warming have yet to be determined. What climate experts do not want to tell us is that the increase in CO2 in the atmosphere also enhances farming.

Doug Glenn: It also enhances plant growth.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Exactly. That’s not something that they want to talk about at all. Climate is something that happens over a series of decades. The fact that it’s a hundred degrees today is of no consequence whatsoever or the fact that you’ve had a five-inch rainfall. Just recently in this past spring, you saw on the news that we had monsoons in Pakistan. There was flooding and people died. I happened to be old enough to remember seeing that on the news in the 1960s.

This isn’t something that’s new, the flooding of those deltas, the receding. It’s just part of the cycle of life in that part of the world.

Do renewables have a place in our power system? They absolutely do, but not as a primary source. The other thing about renewables is that, there’s an aphorism that’s used in the industry, and it’s called “dispatchable generation.” Dispatchable generation is what backs up renewable energy when it is not working.

Doug Glenn: It’s the more steady-state energy producers.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Correct. We decided we would do this with batteries. Today, for as many battery plants that have been put in place to back up renewable energy systems, there are still twice as many that utilize water pumping. You pump water to an elevation that’s higher from where there is a hydro plant. Then when you need it, you drain the water through the hydro plant and you generate electricity.

How does that work out? Let’s say I have a renewable power, and I’m going to run a pump to pump water uphill, and then I’m going to allow it to flow down. I’m probably going to have to pump it because you’re not going to get enough gravitational fall in this thing to generate this hydro plant. What are the energy losses in that? 20% or 30% or 40%? Those are the kinds of concepts that you struggle to answer, “how do you make it work?”

Doug Glenn: It’s certainly doable. How do you make it doable and practical?

Michael Mouilleseaux: If an average natural gas power plant generates 800 megawatts, and it takes up 30 acres, that’s stereotypical. 800 megawatts of wind energy takes up about 100,000 acres. That’s a 150 square miles. Some say this land can be used for something else, possibly farmland.

What you can’t use it for is grazing land because those wind turbines negatively affect the animals. I learned that in the early 2000s in Germany when I had work that took me back and forth. The Germans had onshore wind farms and they had discovered that negative effect on the animals at that point in time.

Doug Glenn: The human species also would be driven crazy by them.

Michael Mouilleseaux: Wind farms also denude the land. If you have ever been proximate to a wind farm, how do you live with it? The people that are putting these wind farms in do not live approximate to them.

That’s a wind farm. For 800 megawatts of solar, it’s 10 square miles of land, 30 acres. With the solar panels, you don’t have as much open land at that point, so it really is difficult to use that land for anything.

Final Thoughts (57:22)

Doug Glenn: Is there anything else, like a near term policy, that could help us out?

Michael Mouilleseaux: In my mind, it’s all about codifying what we’ve done at this point; we cannot leave it to executive orders because those are reversible.

Doug Glenn: Right, and codifying is going to be very difficult, as you already mentioned. We could probably get it through the House at this moment, but probably not the Senate, so it’s going to be difficult.

About the Guest

General Manager

Erie Steel, Ltd

Michael Mouilleseaux is the general manager at Erie Steel, Ltd. He has been at Erie Steel in Toledo, OH since 2006 with previous metallurgical experience at New Process Gear in Syracuse, NY, and as the director of Technology in Marketing at FPM Heat Treating LLC in Elk Grove, IL. Michael attended the stakeholder meetings at the May 2023 symposium hosted by the U.S. DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy.

For more information: Contact Michael at mmouilleseaux@erie.com.