Parts Cleaning: What the Experts Are Saying

![]() In the past, the topic of parts cleaning was not one that garnered much attention in the heat treating industry, but today, things have changed. Interest in parts cleaning is at an all-time high and that makes the need for parts cleaning discussion of vital importance in all types of heat treatment processes.

In the past, the topic of parts cleaning was not one that garnered much attention in the heat treating industry, but today, things have changed. Interest in parts cleaning is at an all-time high and that makes the need for parts cleaning discussion of vital importance in all types of heat treatment processes.

This article appears in Heat Treat Today's 2021 Automotive August print edition. Go to our digital editions archive to access the entire print edition online!

Heat Treat Today wanted to discover why parts washing is such an important step in the heat treat process and about its growing value, so we contacted respected industry experts for an in-depth analysis of the growing popularity of this important step in heat treating.

The following experts contributed to this analysis: Fred Hamizadeh, American Axle & Manufacturing (AAM); Mark Hemsath, Nitrex Heat Treating Services (HTS); Tyler Wheeler, Ecoclean; Experts at Lindberg/MPH; Andreas Fritz, HEMO GmbH; Richard Ott, LINAMAR GEAR; and Professor Rick Sisson, Center for Heat Treating Excellence (CHTE) at Worchester Polytechnic Institute (WPI).

Heat Treat Today asked 13 questions regarding parts washing and encouraged the experts to answer as many as they wished. The following article is a compilation of their experienced insight.

What role does parts cleaning play in the heat treat process and component quality? What is the cost or consequence for heat treating when cleaning is not done correctly? Any anecdotes you can share with us?

Director of

Heat Treat & Facilities Process

American Axle & Manufacturing

Fred Hamizadeh, the director of Heat Treat & Facilities Process at American Axle & Manufacturing (AAM), says, “As a captive heat treater (supplying parts that are used in a final assembly), cleanliness of parts is of paramount importance to the longevity and durability of the final product. Parts that are completely unclean prior to heat treating can cause non-uniform case; and uncleaned parts after quenching can cause a multitude of issues, from failure in post-heat treat operations to higher cost of tooling due to contaminated surface, to fi res in temper furnaces from burn-off of the remnant oils on the surface of parts.”

Vice President

of Sales, Americas

Nitrex Heat

Treating Services

Mark Hemsath, the vice president of Sales, Americas, at Nitrex Heat Treating Services replies, “For many surface engineering treatments like gas nitriding and ferritic nitrocarburizing, surface cleanliness is very important. Various oils and organic substances can impede—selectively or broadly—diffusion and surface activity. Some surface contaminants will bake on or ‘varnish’. Some can be removed with slow heating and purging or vacuum, or even surface activation, but it is not a reliable science. Either way, by positively cleaning them beforehand, problems are avoided. The issues occur when the composition and/or concentration of surface contaminants are not well known or preannounced. Pre-washing and cleaning take time, cost money, and must be studied and discussed with customers prior to any start of production. When parts are promised ‘clean', but arrive coated in an unknown rust preventative or cutting/forming oils, they need to be cleaned.”

Product Line Manager

Ecoclean

Ecoclean’s Tyler Wheeler, a product line manager, shares, “Cleaning plays a critical role that will directly affect the success of the heat treating process. While sometimes looked at as a nonvalue-added process, the consequences of not cleaning correctly are many and can be costly. Depending on the method of heat treating, quality issues may range from staining, discoloration, inconsistent properties, and even damage severe enough to scrap entire batches. Not only are there consequences for the workpieces themselves, but these problems may extend to damaging the heat treating equipment itself, leading to downtime and expensive repairs.”

The experts at Lindberg/MPH report there are several benefits to cleaning parts prior to any heat treating. They say: “By washing the parts prior to heat treating, it assures that the furnace chamber will remain conditioned and free from vapors, resins, binders, or solvents that could attack the refractory lining or heating elements and cause pre-mature failure of those items.”

What about the cost or consequences when the cleaning is not done correctly? “Washing parts prior to any thermal process, removes any layer of machine or cutting oils etc., which can be baked on and require additional and costly processes such as grit blasting, machining, or grinding to remove the unwanted layer on the surface of the parts.”

The Lindberg/MPH experts had an interesting anecdote to share about the importance of parts cleaning: “A customer was using a simple spray washer to clean small sun gears with an inner spline. The parts were to be carburized afterwards. The spray washer didn’t remove the machine oil used in the broaching process. During the carburizing process, the machine oil acted as a shield and didn’t allow the carbon to penetrate the ID properly, thus causing part failure on the gears. Afterwards, a dunk washer with heated water and a dry-off was purchased to clean the parts.”

Andreas Fritz, CEO at HEMO GmbH, explains, “Cleaning has always played a role in heat treatment. The question was always, ‘How clean is enough to keep the cleaning process as cheap as possible?’ Nowadays, especially in LPC or nitriding processes, the cleaning quality is at least equal to the hardening quality, because heat treaters understand that these processes belong together. There are no good hardening results without good cleaning quality.”

Additionally, Fritz continues, “a cleaned surface lowers the risk of defective goods after heat treatment by helping to provide a very good hardening depth and compound layer.”

Fritz shares a company-altering anecdote: “In the mid-1990s, we sold the first machine to a Bosch automotive supplier which had a captive heat treatment department. They delivered the cleaned and then hardened goods to Bosch, and their QM sent the goods back stating they were not hardened.

“Our customer asked if they checked the hardening quality, and Bosch replied: no, because the parts were not black; therefore, coming to the conclusion that they had simply forgotten to harden them. The supplier invited them to see that the parts were cleaned in a new way with a solvent-based cleaning machine under full vacuum. Since they came out spot-free after cleaning, there was no oil left, which formerly cracked on the surface and left the black color. The result was that for a couple of years, Bosch wrote on drawings that the parts had to be HEMO-cleaned before hardening. This was our start in the heat treatment industry and today, we make 50% of our annual turnover there.”

LINAMAR GEAR’s Richard Ott, a senior process engineer, offers his perspective, “Pre-cleaning and post-washing are very important because all parts coming into our plant can’t have any contamination on them. After heat treating, all parts are washed and blown off before temper.”

Historically, cleaning has not received the attention it deserves in the heat treat process. Have you seen any positive changes in perception among heat treaters in recent years?

Wheeler of Ecoclean addresses the perception of value: “Historically, the cleaning process has been looked at as a non-value-added necessity of manufacturing. However, this attitude is becoming a thing of the past for companies who invest in a quality cleaning process. As of late, customers have placed a greater focus on their cleaning processes both before and after heat treating as quality and production demands continue to increase. A proper cleaning process can eliminate scrap, increase uptime, and lead to a better-quality product for the end customer, which may translate into additional orders. When considering the holistic benefits of a proper and robust clean process, the old mentality is starting to change.”

The experts at Lindberg/MPH reply, “For many years washing parts before or after heat treating was considered an optional process and often bypassed. Today, most commercial and captive heat treaters are using parts cleaning as a necessity, particularly in the growing vacuum heat treating sector, where any contamination is detrimental to the hot zone and pumping systems.”

HEMO’s Fritz explains, “Commercial heat treaters specifically, changed their minds very early because they saw the chance to cover the various cleanliness demands of all hardening methods and processes with one single cleaning system. The hybrid cleaning system which made it possible to clean with solvent or with water or in combination in the same machine, made it possible for them to ensure hardening quality for any incoming good, no matter which residue was on it.

“They were able to cut down costs by using only one cleaning system and by increasing the income per ton due to increased quality and less defective parts.

“The captive heat treaters changed when they sent parts outside to commercial heat treaters while they did annual maintenance or when they didn’t have enough of their own capacity. The returned parts were of much better quality; and they started introducing this kind of cleaning system as well.”

Hemsath of Nitrex agrees about rising standards: “Similar to other areas of heat treatment, OEMs continue to raise their standards for part cleanliness. Sometimes these standards are rooted in functional requirements such as minimizing the number of foreign particles in a closed system in the finished product and other times the requirements are purely aesthetic. In either case, the result is that, in recent years, heat treaters have been required to devote more resources to improve their cleaning processes proactively during the quoting/process design stages, or reactively as a result of non-conformance. Many commercial heat treaters have come to understand that evaluating the cleaning needs of a part and implementing a robust cleaning process before production begins results in a better customer experience as well as improved long-term profitability.”

AAM’s Hamizadeh concurs with a positive change in perception: “Yes! As automotive industry reliability demands are increased, more and more attention is placed on all aspects of cleanliness, which includes heat treat washers.”

Ott, of LINAMAR GEAR, shares evidence of the rise in parts cleaning importance, saying, “Yes, our washers are checked twice a day for concentration and cleanliness.”

How can heat treaters determine their cleaning needs?

George F. Fuller

Professor and Director of the Center

for Heating Excellence (CHTE)

Worchester Polytechnic Institute

Rick Sisson, the George F. Fuller Professor and director of the Center for Heating Excellence (CHTE) at Worchester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), explains, “The incoming materials should be carefully examined visually to identify the type and quantity of surface contamination. Look for heavy oil, light oil, cutting fluids and/or rust, and scales. The cleaning process should be selected to remove the type of surface contamination identified. In general, a cleaning process should be included prior to heat treating to ensure a predictable response to the heat treating or surface modification process.”

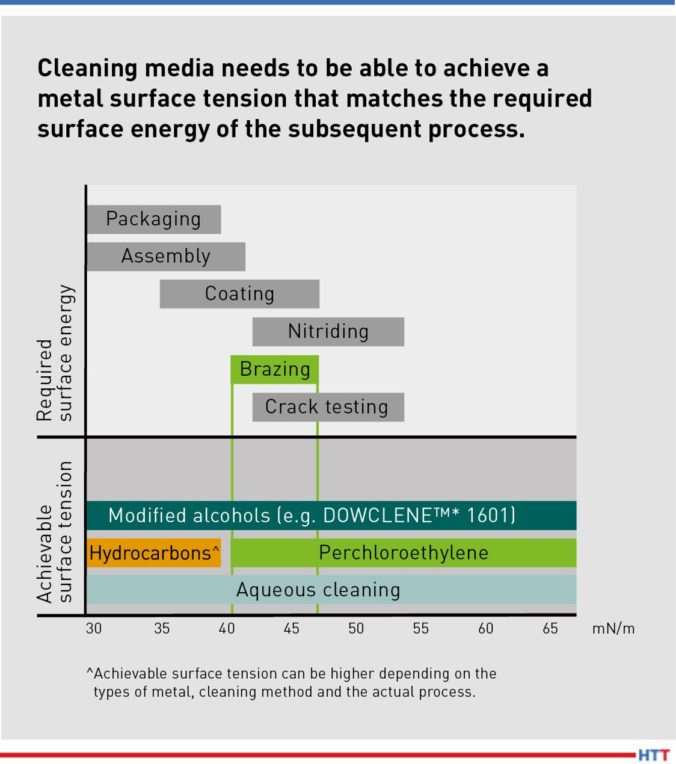

Sisson continues, “The heat treater must confer with their customer to determine the post-heat treat cleaning requirements. If the part will be ground or machined after heat treat, then post-heat treat cleaning is not required. However, if the part is ready to be shipped, then the appearance is important. For medical applications, any discoloration may be a cause for rejection. The surface finish may be important and should be discussed with the customer.

“The pre-heat treat cleaning requirements are determined by the effects of cleanliness on the heat treat performance. For surface treating, a dirty surface may affect the carburization or nitriding performance. Nitriding is very sensitive to the surface cleanliness. A fingerprint can inhibit the nitrogen uptake and result in soft spots. Carburizing is less sensitive to oils and grease, but corrosion products may inhibit the surface reactions and cause soft spots. However, it is best practice to examine the preheat treat parts and clean away the oils and grease. Corrosion products (aka rust) and cutting fluids ensure a uniform response to the heat treating process,” Sisson concludes.

Hamizadeh of AAM states, “Most customers should have a specification. Start by reviewing the provided prints and follow up with the final customer to determine if parts are further washed with dedicated process washers prior to installation in the final product.”

He concludes, “Nevertheless, heat treaters must provide a part which is clean, uniform in color, and free of quench oil on surfaces and cavities. Parts must also not exhibit any markings from oxidized quench oil (tiger stripes), either.”

“We are in-house heat treaters. Our customers require spotless parts and if they’re not, then we need to clean them,” explains Ott of LINAMAR GEAR.

Fritz from HEMO shares his perspective: “Heat treaters usually have their own labs to check the hardening quality. If the quality is not stable, the cleaning could be the reason. Additionally, they could send parts outside to be cleaned in a different way. Then do the hardening in their shop to see if there is a difference. In most cases, their customers tell them if the quality is not good. We are then the ones to offer our experience and take them to the next level.”

Ecoclean’s Wheeler describes their process in determining cleaning needs: “When determining the needs of a cleaning system, it is essential to understand the incoming contaminants on the part. In addition, one needs to understand which upstream manufacturing processes were used, the requirements of the heat-treating process, and which type of heat-treating process is being used. Not all cleaning systems are created equally, and not all approaches work in every scenario. For example, phosphate-coated parts coming from a stamping process will require a different cleaning system than a machined part. Working together closely with your cleaning equipment supplier is the best way to ensure that the best cleaning process is implemented for your specific application.”

How do the requirements for cleaning differ between pre- and post-heat treating?

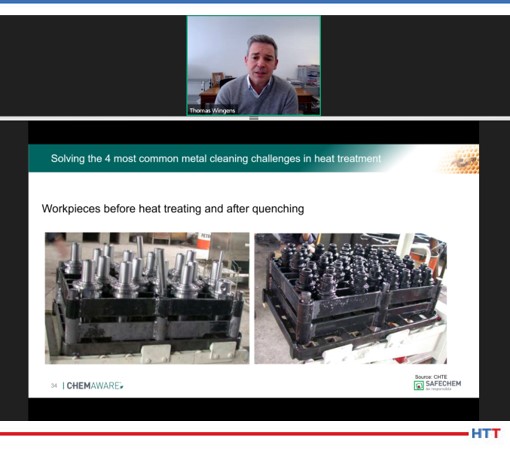

The experts at Lindberg/MPH explain: “Pre-washing parts ahead of heat treating is needed to remove any oils or solvents that can remain on the parts. Also, some parts can hold wash water and some residue that can be carried into the furnace, and those must be blown-off or dried before the next operation.”

They continue: “Post-washing parts, particularly after oil quenching, is needed to remove any oil that might be trapped—parts such as pistons, valves, and gears with recessed areas. Most of those batch washers are fitted with a dunk or oscillation feature where the load is completely submerged, then drained and dried before moving to the tempering process. For many years, a single washer was used for both pre- and post-washing, but that practice has largely stopped.”

Nitrex’s Hemsath states, “When oil quenching in vacuum oil quench furnaces or standard integral quench furnaces, the oil is known, and it must be removed prior to temper operations. Quench oils are often difficult to remove completely, especially in hot oil quenching applications. Tempering can help with further removal of the oils, or it can make the situation worse by baking on quench oil residues into tough, difficult-to-remove deposits. With post-cleaning, the contaminants are well known, and they do not impede the heat treatment or surface engineering.” Hemsath continues, “Contaminants on the part’s pre-heat treatment must be removed for vacuum furnace operations to protect the equipment and prevent carbon pickup on the parts. Pre-contaminants must also be removed to help with processes such as gas nitriding, FNC, and low-pressure carburizing (LPC). Since LPC is a vacuum process, precleaning is more critical than with gas atmosphere carburizing, where the hot hydrogen gas can be effective at assisting with pre-cleaning of parts. However, even in atmosphere heat treating, minimizing the number of foreign substances entering the furnace on each part will help ensure a more consistent process and extend quench oil life.”

Wheeler of Ecoclean states, “Different goals and objectives drive the requirements of the pre-and post-heat treat cleaning systems. A pre-heat treat cleaning process aims to remove all contaminants produced by the upstream manufacturing process that could negatively affect the heat treating process. Without a proper pre-cleaning process, the heat treating may not be effective, parts could be damaged, and even the heat treating equipment itself could face damage. The goal of the post-heat treat cleaning system is to ensure that the final product meets the quality demands of the customer or end-use application. The needs of these systems may be driven by strict specifications which limit the number of allowable particulates and even the maximum size of each particle.”

Hamizadeh of AAM agrees that the processes are in no way similar. He says, “Drastically different. Pre-wash is intended to clean the product from any upstream contaminants, cutting fluids to provide a clean, uniform surface for process. Additionally, pre-wash is used to protect the heat treat equipment from contamination from oils and chemicals, which will have an adverse effect on lining or internal alloy components of the furnaces.”

He further explains, “Post-washers are historically built to remove the bulk quench oil from the part. However, it is more common that parts have irregular shapes, hidden holes, and geometries that make it difficult to remove trapped oils.”

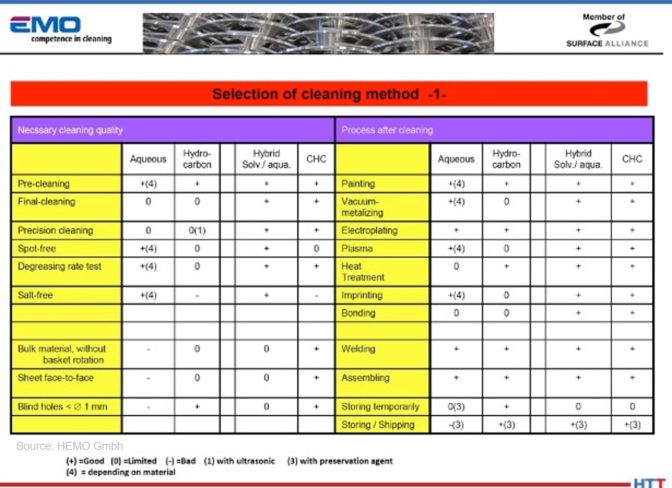

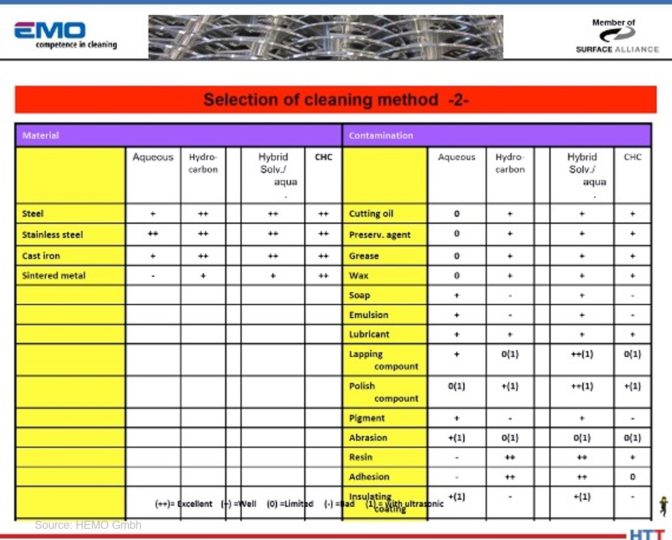

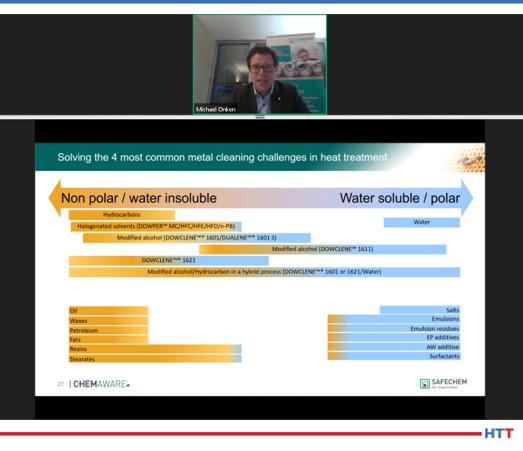

“In the case of pre-cleaning, we make a difference between organic and inorganic residues,” Fritz of HEMO contends. “An old chemical says, ‘Similar dissolves similar.’ Hence, it is important to identify the residues of parts before pre-cleaning.”

He continues, “Water-based coolant should be cleaned with water and detergent because solvent would leave white spots caused by salts.”

“Oil is organic and should be removed by solvents like hydrocarbon or modified alcohol because water and oil are not a good mixture,” explains Fritz. “Anybody who first cleans an oily pan before a glass in the same bath knows that. Sometimes the parts have both kinds of residues on them due to several production processes before heat treatment. Then a hybrid cleaning machine is the perfect solution, because it first takes away the organics with solvent and then the inorganic spots with water.”

He concludes, “In the case of post-cleaning, we mainly talk about cleaning after oil quenching. In this case, water is the worst solution because the cleaning quality is not good, and the amount of wastewater is immense. A pure solvent machine is the best option for this scenario.”

How does cleaning differ between commercial heat treat shops and in-house/captive heat treat departments?

Sisson of CHTE describes the difference this way: “The need for cleaning remains the same. Captive heat treaters will have the benefit of heat treating the same parts over time and should document the contamination identified and the cleaning methods used. Frequently the parts will be coming from a machining or surface finishing operation. A discussion with the machine shop will identify the contamination.

“Commercial shops will see a wide variety of parts and should develop an incoming materials evaluation process to determine the type and extent of surface contamination. As part of this incoming material evaluation process a cleaning process should be specified for each incoming part. The process to remove grease and oil is different from corrosion products.”

How clean is clean anyway? How can one determine cleanliness? How can heat treaters identify the right cleaning method for their applications? What should they pay attention to?

“Specifications based on design and final function of the part will determine the cleanliness requirement,” Hamizadeh of AAM points out. “It is imperative to determine the cleanliness requirements prior to processing the parts. This could be surface chemical, oil contamination, or particulate allowed on part in terms of grams allowed per part or number of particles of determined size per part. Pay attention to customer contractual requirements based on RFQ or part print, or customer specs as stated in part drawings.”

“When answering this question, we need to ask ourselves: ‘What is the end goal of the cleaning process and what contaminants am I removing?’” Wheeler of Ecoclean begins. “Not all contaminants are created equally, nor will they successfully be removed using the same approach. The types of equipment, process steps, machine parameters, and chemicals used for cleaning need to be chosen carefully to ensure a successful and robust process.”

He explains: “Cleaning prior to heat treating is focused on preparing the parts for a successful heat treat, which means we need a surface free of oils, coolants, and particulates. In addition to the cleaning aspect, it is also crucial to sufficiently dry the parts before treating them to prevent damage during the heat treating process. A simple test to check for cleanliness prior to heat treat is to perform a ‘water break test,’ where clean water is rinsed across the surface with a goal of seeing a continuous film of water running across the whole part without being interrupted. A more scientific approach involves measuring the surface energy of the piece by using a contact angle measurement tool or Dyne pens.”

Wheeler clarifies: “When asking how clean the parts need to be post-heat treatment, there may be drastic differences based on customer quality requirements and the end-use of the workpiece. These requirements can range from simple visual cleanliness checks to strict maximum residual particle size limitations. The evaluation for conformity to these high-end specifications will require the use of multiple pieces of lab equipment, including expensive particle measuring and counting microscopes.” CHTE’s Sisson illustrates, “As we have seen in old movies, the butler wears white gloves and after rubbing the surface any contamination can be seen. There is a limited number of types of surface contamination for heat treaters to identify: heavy oils, light oils, cutting fluids, and corrosion products (rust and scales). Knowledge of the part history will help identify the contamination and therefore the cleaning method.

“The largest impact will be on nitriding and ferritic nitrocarburizing (FNC) processes. Surface contamination inhibits the absorption of nitrogen by interfering with the decomposition of ammonia on the steel surface. Even the grease from fingerprints can cause soft spots,” he concludes.

HEMO’s Fritz shares, “Clean can be visually clean or when you wipe a cleaned part or when a part is not dirty after the hardening process because it was cleaned well before.”

In determining cleanliness, Fritz continues, “Optically, for example, use an ink pen that shows the surface tension. A high surface tension shows a well cleaned surface.”

And finally, identifying the right cleaning method and focus: “First thing is to always identify the residues which are on the parts. If this is identified the cleaning process can be selected accordingly.”

What might be the impact for furnaces if components are not cleaned thoroughly?

Fritz of HEMO answers, “The residues vaporize and crack on the furnace walls. The walls then must be stained new in short intervals. This can be prevented by using a better cleaning system.”

“Heat treating oily parts will cause the oils to burn and fill the room with smoke and oil vapors. These gases and the smoke will deposit in the furnace and reduce performance and furnace life,” shares Sisson of CHTE.

The experts at Lindberg/MPH explain, “For many years unwashed parts were placed in tempering furnaces to burn-off the machine oils rather than washing. Over time, all that machine oil saturated the furnace brickwork or coated the heating elements, which had to be replaced much sooner than needed. Today, due to some environmental issues, that ‘smokebomb’ has become a problem, and the washer has become a sound solution and a proven benefit.”

AAM’s Hamizadeh says, “I’ve seen carburizing furnaces become contaminated with chemicals from prewash. They glazed the hard refractory into a glass and caused adhesion between silicon carbide rails and alloy base trays.” He continues: “We’ve also seen excessive smoking from temper progress to an occasional, but rare fire in a temper furnace or a more probable fire in exhaust ducts due to oil film build up.”

What cleaning options are available? What are their pros and cons?

“Traditional batch or continuous spray washers with or without dunk is an absolute minimum,” states Hamizadeh of AAM. “Other equipment such as Aichelin’s Flexiclean Vacuum washer can do a fabulous job without the use of solvents. Today—as a minimum—prewash systems should have a 3-tank system of wash, rinse & rinse, and blowoff. Post-washers should have 4-stages: 2-wash, followed by 2-rinse, and blowoff dry stage. Conventional washers are very cost-effective. Newer technology washers, with the use of advanced skimmers, multistage filtration, and ultrasonics to get the best agitation possible, will improve the capability of the machine. Dedicated and custom designed line washers perform the best, but also cost the most.”

HEMO’s Fritz shares, “I think the inline water-based dip and spray cleaners with hot air or vacuum drying are still fine for 50% of all applications in heat treatment. Anything else would be too expensive and simply not necessary. But for higher demands, more sophisticated systems are necessary. There you find top or front-loading full vacuum machines which can run water with detergent, solvents, or both.”

“For most washers, added features such as skimmers, oil traps, and dual-can type filters are very popular,” point out Lindberg/MPH experts. “These options help in keeping the washing media cleaner and free from loose metal, chips, and free carbon. The cost of these items is minimal compared to dumping several hundred gallons of water and many chemicals on a regular basis.”

They conclude, “Most washers, especially those fitted with the dunk features, are built with stainless steel tanks and all structures that are submerged in the washing solution. The extra cost for stainless steel far outweighs the cost of replacing a mild steel-lined tank or coated tank, which both have a much shorter life than the stainless-steel units.”

Apart from technical cleanliness, are there other aspects that heat treaters should consider in their choice of the right cleaning solution? Do certain materials demand specific cleaning precautions? What cleaning methods will be particularly suited to specific types of soils?

LINAMAR GEAR’S Ott says, “Washer chemistry that will remove oil and other surface contaminants and possibly leave a protective coating on the parts may be worth developing, so that flash rusting will not occur before the tempering operation.”

AAM’s Hamizadeh explains, “For specific parts and materials, specific washers with specific chemicals are needed. All parts should be compared to detergents used, temperatures, and agitation/spray pressures they can endure.”

“They should consider the quality of the final product,” Fritz of HEMO details. “They should consider environmental issues like wastewater, amount of detergent, heating energy, etc. They should consider cycle time and the degree of cleanliness required. Altogether it will lead them to a total cost of operation consideration, and they will find out that a high investment doesn’t mean higher operating cost over the lifetime of the equipment.”

He shares that “Copper and aluminum, especially, must be handled with care when selecting a way of cleaning.”

What common issues do heat treaters experience in the cleaning process? And how can these be avoided?

Nitrex’s Hemsath explains, “There are various methods for cleaning from vapor degreasing to ultrasonic methods. Each has benefits and negatives, such as environmental impact issues or cleaning of various contaminants completely. Another issue is part orientation and cost of parts handling. Continuous small parts cleaning can allow better part orientation, say, for cylinders. However, the labor content adds to costs for individual parts placement. No operation, especially commercial heat treat operations, can have all the cleaning options. It is not uncommon to hand-clean parts that are difficult to clean in a batch or continuous processes. The biggest problem is not knowing what the exact contaminants are.”

“Complex part geometries and pack density of the load are common load issues that are faced. Regular maintenance of washers—filters, skimmers, titration practices to maintain chemical balance—will all affect their performance. A regimented SPC and quality control specification should be required to ensure all work is completed and signed off by appropriate quality team members,” states Hamizadeh of AAM.

Fritz of HEMO cautions, “The biggest issue is the white layer or spots on the parts which result from inorganic residues. They pollute their water-based cleaning media with oil and other organics and then the media is not strong enough to additionally clean off the inorganics. This can cause soft spots on the surface after the hardening process. “The second big thing,” he says, “is that the cleaning quality is decreasing with every cycle. In a solvent machine with a good distillation device, you always have a constant quality.”

Have you noticed any changing requirements or expectations in terms of cleaning quality for heat treat processes over the last 5 years?

Hamizadeh of AAM answers affirmatively, “Yes. Tighter specs for amount of carry over oil or oil residue on parts.”

HEMO’s Fritz concurs, “The requirements change because the industry is changing. We go to electric vehicles, which means we need to harden new kinds of parts that are made of new kinds of materials, alloys, and composites. This means a modification of the hardening and of the cleaning process.”

Ott from LINAMAR GEAR has noticed, “Parts are compared to vacuum heat treat, so the cleanliness is very important, especially in automotive.”

What challenges do you think will confront heat treaters in the next 5 years, specifically regarding parts cleaning? Where do you see trends heading?

“Electric drive units will require a reexamination of the part washing and available technologies. It’s going to become more difficult. Not easier,” believes AAM’s Hamizadeh.

Fritz of HEMO predicts, “The main challenge will be to stay alive. With the rise of the electric car, fewer parts will be heat treated. Heat treaters must offer the best possible quality for reasonable prices in order to survive. This is not possible with the old way of cleaning.” He sees trends “. . . still going to vacuum. LPC is very strong and will be increasing. Additionally, gas and plasma nitriding will increase. Especially in those cases, a clean surface is the only way to have a reliable hardening process with consistent quality.”

Fritz concludes, “The other trend is small batches. That is the reason why we redesigned our small cleaning machines to also be able to survive in the heat treatment environment.”

“Totally clean parts,” is the challenge Ott of LINAMAR GEAR sees.

How can heat treaters balance the need for component cleanliness and cost-effectiveness for their operation?

Ecoclean’s Wheeler maintains, “When searching for the balance between cleanliness and cost, defining what costs are genuinely associated with cleaning is essential. Some of these costs may be obvious, while others may not be so clear at first glance. In too many instances, the actual lifecycle costs of owning and operating a cleaning system are not taken into consideration as the main focus is instead the upfront investment of the machine itself.

Utility costs, chemical usage, waste disposal, and maintenance are only some of the expenses that will add up over the life of a piece of equipment which may significantly impact its cost-effectiveness over an alternative solution. One example in this instance is using a vacuum solvent cleaning system over an aqueous-based machine. While the solvent system will typically come with a higher upfront purchase price, it is generally more cost effective to own in the long run when compared to the water-based system.”

Wheeler continues, “The other question that one should ask when deciding on how much to spend on a cleaning system is what the cost of purchasing the wrong system is. How much will be spent on scrapped parts, repairing damaged heat treating equipment, and downtime caused by the improper cleaning of parts? These may not always seem obvious upfront, yet they are actual costs that every manufacturer may face. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach for every company, it is essential to consider all obvious and hidden costs associated with the cleaning process when looking for the balance between price and quality.”

“For captive heat treaters,” Hemsath of Nitrex answers, “their contaminant stream is much better understood, and a solution can be custom engineered to provide repeatable results. For commercial heat treat facilities, cleaning operations have to satisfy many part sizes, orientations, and a multitude of contaminations that are often not well understood. So, the cleaning operation must be a process that gets most of the contaminants on most of the parts. Good communication with the part maker is essential to prevent problems, especially in long-term programs where the same parts are heat treated for many years.”

“They must do a total cost of operation examination of their whole process in order to find the right system,” encourages Fritz of HEMO.

These experts have spoken and offered much valuable insight into the world of parts cleaning. No longer can this process be viewed as “a non-value-added necessity of manufacturing,” as Tyler Wheeler of Ecoclean observed. Today, parts cleaning is proving to be an important component for success in heat treating.

For more information, contact the experts:

Fred Hamizadeh, Director of Heat Treat & Facilities Process, American Axle & Manufacturing, Fred.Hamizadeh@aam.com

Mark Hemsath, Vice President of Sales, Americas, Nitrex Heat Treating Services, mark.hemsath@nitrex.com

Tyler Wheeler, Product Line Manager, Ecoclean, Tyler.Wheeler@ecoclean-group.net

Lindberg/MPH, lindbergmph@lindbergmph.com, 269.849.2700

Andreas Fritz, CEO, HEMO GmbH, a.fritz@hemo-gmbh-de

Richard Ott, Senior Process Engineer, LINAMAR GEAR, Richard.Ott@Linamar.com

Rick Sisson, George F. Fuller Professor & Director of the Center for Heating Excellence, Worchester Polytechnic Institute, sisson@wpi.edu

technical Tuesday

Parts Cleaning: What the Experts Are Saying Read More »