Heat Treat Radio #106: Heat Treat Legend Doug Peters

“Don’t lose sight of who you are . . . .” In an industry where passion to create, help, and discover can become all-consuming, Doug Peters’ drive and dedication to the heat treat industry has not compromised his care to family, employees, and the joys of life. As the founder and CEO of Peters’ Heat Treating, this Heat Treat Legend joins Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn, in a special episode.

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

HTT · Heat Treat Radio #106: Heat Treat Legend Doug Peters

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Meet Doug Peters (01:05)

your Reader Feedback!

Doug Glenn: Doug, it’s really good to talk with you. We’ve known each other for many, many years, but it’s really nice to get a chance to sit down with you here on Heat Treat Radio’s Heat Treat Legend — it’s an appropriate title for you. I’m really glad you took the time to talk to us. Welcome to the episode.

Doug Peters: Thanks, I appreciate it.

Doug Glenn: The first thing we do in these episodes, Doug, is just kind of give people a sense of you, the person, before heat treat. How did you get into the industry and a little bit of the history of your experience? Why don’t you start with where you are located, as well?

Doug Peters: We’re located in Meadville and McKean, Pennsylvania; we have two plants. The total square footage in the plants is probably roughly 70,000 square feet.

My history goes clear back to my farm days. Our family farm, which has been in our family since 1885, opened a retail milk store in 1963. My mother had no babysitter, so I had to go to work with her. During that time, I was taught how to prepare a storefront, and by the time I was 12, she had me cashing out the cash register, and reconciling all receipts at the end of the day. When “Mrs. Brown,” who was elderly, pulled up out front, you went out and met her at the car and got her bottles for her, and helped her in and out of the store. A good amount of my business acumen, believe it or not, came from my mother and that experience.

Source: Peters’ Heat Treating

I graduated from Penn State University with a degree in business but, enroute, tried to be a pharmacist, so I ended up with 40 credits in the sciences. I went into the insurance business because I felt as though I needed some toughening up, people-wise. I ended up being an insurance agent for three years and had one question that I always asked customers and that was: “If I’m a genie and I can grant you one wish, what would it be?” And every tool shop I called on said, “We need a good heat treater.”

I had worked for my wife’s father in a tool and die shop, in the summers, as a saw boy, etc., so I sort of knew what heat treating was. Well, I went and discussed it with my wife’s father, and he gave me the name of a gentleman who had just retired from Talon after 32 years in their heat treating department. I called him on the phone, I paid him under the table, and he taught me the trade. Without him, I wouldn’t be sitting here today.

Likewise, my father-in-law bought us a building and gave it to me one-year rent-free, and my father, who was a railroad engineer, showed up every day after a full shift, and helped me fix the old broken-down equipment that I had bought to start the business.

Then there was Jackie, sitting behind the scenes. She did all the books. She was a full-time schoolteacher. I went three years, to the day, without a paycheck. My first paycheck was $100.

That’s how I got started.

Doug Glenn: What year did you actually start the heat treat?

Doug Peters: 1979, October of 1979.

Doug Glenn: October of ’79 you started the heat treat. Wow. And there is great family involvement too, right? Your dad, your father-in-law, Jackie . . .

Doug Peters: Yes. You know something? You certainly can’t accomplish anything by yourself. Without those guys and Jackie, we would not have been able to do what we did.

Doug Glenn: That’s great stuff.

Help me with the math. How many years was that ago?

Doug Peters: In October 2023, it would have been 44 years ago.

Major Accomplishments (04:40)

Doug Glenn: So, in the 44 years, what are the highlights? Are there one or two, or two or three, major accomplishments that, when you look back, you say, “You know what? This was a major accomplishment or something pretty significant.”

Doug Peters: I think probably the most satisfying thing to me are the families of the employees that we’ve had over the years. I’ve watched them get married, buy homes, have children, have grandchildren, and we’ve been very lucky to keep a very tenured staff over the years. Being involved with not only the employees but our customers within the community. Being able to contribute and help people as a result of what we do here in the heat treat — it’s really been the most satisfying thing for me.

Doug Glenn: I don’t want to underemphasize that. I think that’s a classic Doug Peters answer too. You know, you are one of the most “people oriented” people I know, which is great. I told my wife, when we were starting Heat Treat Today: You know what I’m looking forward to, is paying people. I don’t know why I was looking forward to it, but I was. So, I appreciate that perspective.

Does anything jump to your mind as far as actual business accomplishments? Is there anything that happened over the years, like, for example, opening the McKean plant?

Doug Peters: Yes, I suppose, if you look at those things. To me, those were just normal forces of business to better serve customers.

We started out with four little box furnaces with maximum capacity of 20 pounds. My first employee was my loyal dog. As we moved forward, I was lucky enough to work for a very innovative group of customers. We were on the cusp of tool and die morphing with the advent of computers into enabling (or demanding) us to really do more than traditionally what heat treating had been responsible to do.

For instance, one of the early things we did was we learned how to not control size, but influence size on a particular part and design to eliminate hard finish time on tooling. That was one of the things we did a lot of work in. We did a lot of work in straightening.

Early cryogenics work. I mean, back in 1980 and 1981, I bought a machine that would take gaseous CO₂ and compress it into very pithy dry ice. Then, utilizing ethyl alcohol as a catalyst, I could drive temperatures to -70/-75 degrees. Experimenting with that, we found that we could improve the stability of materials that were being manufactured in the shops, but most of all, improve part life. So, that was the advent of us getting into liquid nitrogen cryogenics, in the very early ‘80s.

From there, we graduated into vacuum furnaces. We have nine vacuum furnaces, presently. In 2006, we bought 20,000-pound nitriders that can do up to 138 inches in length. Then, of course, the specification requirements grew and grew, as we moved forward.

Source: Peters’ Heat Treating

At this point in time — and I’ve got to give my son-in-law, Andy, my daughter, Diana, and his staff a lot of credit — Jackie and I had a company that was ISO, and we could work the ASM2750 pyrometry specifications. When Andy and Diana came on board, they took us to Nadcap. Andy just put in a destructive testing laboratory. For instance, we just had our first AS audit, so those capabilities are now online.

And we’ve grown to nearly 80 employees. When you look at the major accomplishments over the years, a lot of the technical-credit goes to the people out on the shop floor who really put their shoulder on the wheel and pushed with us to go through the disciplines that are required to gain those things.

The Metal Treating Institute (09:18)

Doug Glenn: I’d like you to address two other questions on accomplishments, if you don’t mind, Doug. You and I have had a long history in the Metal Treating Institute. I’d just like you to have a comment about your activity there, including the fact that you were a president. Then, also, would you be comfortable commenting on Laser Hard?

Doug Peters: Sure!

As far as MTI, our company would not be successful without MTI — or as successful as it is. We’ll give Jackie the credit.

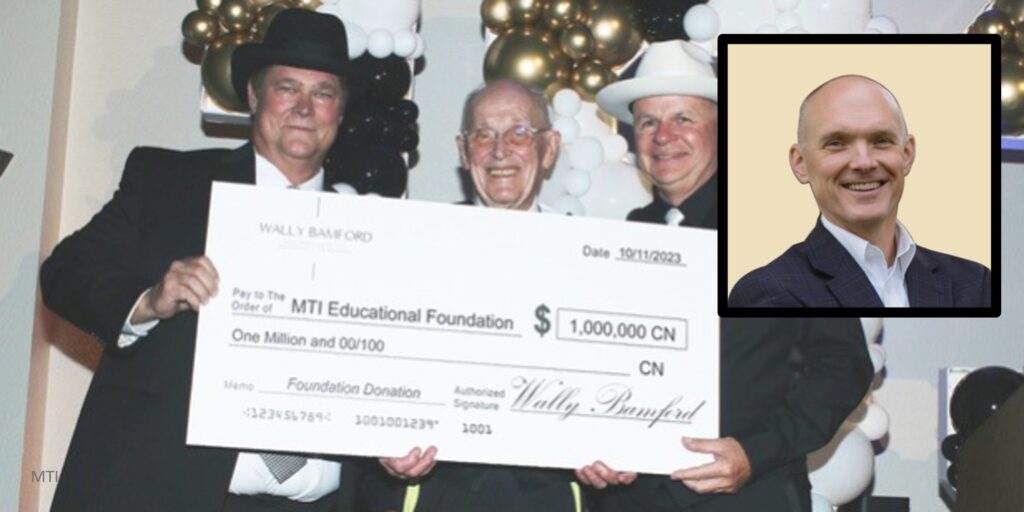

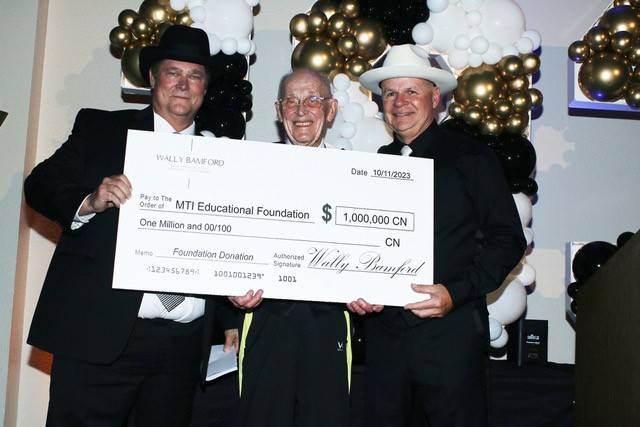

In 1984, I bought a fluidized bed from Wally Bamford. As we sat at dinner, after we had signed the purchase orders that evening, Wally shoved an application for MTI under my nose, and he said, “You’ve got to join this organization.” I asked him what it was about, and he told me, so Jackie and I joined. But we didn’t do anything for four years, except look at the sales reports and everything else.

Well, my wife signed us up for our very first meeting in 1989. Once we got there, I went, “Oh my goodness, have I been missing out on how to grow the company?” It was at that meeting that I met Chet Walthall and Roger Keeran, who ended up being wonderful mentors and friends of mine. I treasure those guys so much.

The other fellow that I met through that journey was Jack Ross who owned Ironbound. Jack would allow you to come into his plant and he’d share anything, as long as you were an MTI member — that was his only requirement.

Lance Miller was our executive secretary, at that point. My first involvement at MTI was getting a call from Chet Walthall congratulating me because I was on his education committee. Then, with forward planning — which is now strategic planning — I called Lance and asked if I could go to the meetings being held in Pittsburgh. I was not on the committee but my contention to him was, as a forty-something, I really thought that somebody younger should be on the committee that was planning the future in the institute. So, that’s my involvement, and it just mushroomed from there.

I was the millennial president in 1999 and 2000. I have been on numerous committees, chaired the Education Foundation’s institution with Norm Graves; Norm was the treasurer.

Well, yes, of course, my wife, Jackie, who was our president in in 2015. It was my pleasure to carry her briefcase that year and watch her. Her tenure, at the board level and through the chairs, was longer than mine. She served on numerous committees and she’s received a few awards, and she’s so deserving.

Doug Peters, Founder & CEO, Peters’ Heat Treating, Inc.

Doug Glenn: In fact, if I may interrupt, you were one of the founders of that Educational Foundation, if I’m correct.

Doug Peters: That is correct. And, you know, there were other people on our committee too, but to be able to see what the education foundation has grown to and how it will support the industry moving forward, I am very pleased to have been a part of that.

Doug Glenn: And we’ve got to make another note here, since we mentioned Wally Bamford: It wasn’t long ago that Wally made a very significant contribution to that foundation.

Doug Peters: Well, you’re doggone right.

Our initial bogey was a quarter of a million dollars. We weren’t going to take a nickel out until we got to $250,000. We pushed it over $250,000 and that’s when I stepped aside and we had different folks take chairs. Then we pushed it to $450,000, and now we’re giving scholarships. As a matter of fact, we had a recipient, here at the heat treat, to the Founders Scholarship. Then, of course, Wally, at our 90th anniversary, gave us a million dollars.

Doug Glenn: Canadian!

Doug Peters: Canadian, yes, yes! And I’m going to call Wally to make sure that he listens to this podcast, Doug.

Doug Glenn: It was so typical Wally Bamford, right? He’s up front, he’s talking, and he says, “I’d like to donate a million dollars,” and everybody is oohing and aahing, and he leans in and says, “Canadian” in a deep voice, into the mic. It was classic. Wally needs a lot of credit there.

One other question, before we get off of MTI. Have any other people in your family been the president of MTI that you’d like to talk about?

Doug Peters: Well, yes, of course, my wife, Jackie, who was our president in in 2015. It was my pleasure to carry her briefcase that year and watch her. Her tenure, at the board level and through the chairs, was longer than mine. She served on numerous committees and she’s received a few awards, and she’s so deserving.

Doug Glenn: We share quite a bit in common, right? First off, we have the same names: Doug and Doug. We also have wonderful wives and, if you’re like me, people in MTI can tolerate you, but they really like your wife. That’s the way it works on my side.

Doug Peters: Absolutely. Everybody says “hi” to her before they say “hi” to me.

Doug Glenn: Exactly. We both married well!

So, as far as MTI, thank you for commenting on that. I just felt that was important. That’s one of the reasons why I think both you and Jackie really are kind of heat treat legends. You’ve been very active in a lot of different things, MTI especially.

Laser Hard (14:12)

Tell us briefly about Laser Hard.

Doug Peters: Laser Hard has been a joint family venture. Good friends of ours (and customers), the Learn family has been doing laser welding and cladding for a good number of years and are principals in Alpha Laser in North America. The patriarch, Blair Learn, gave me a call and said, “I want to show you something.” So, I went down and looked at it and, when all was said and done, we decided to partner. He knew lasers and I knew heat treating and we felt as though there was a real need.

The things that we’ve done with Laser Hard, in solving issues that cannot be solved in traditional heat treating, do not cease to amaze me on a daily basis. The type of customers that we’re attracting, including large toolmakers (Tesla, Ford) there are all kinds of people that have come and worked with us on applications that we have had an opportunity to pioneer, literally.

It’s just been a wonderful partnership. I can’t say enough good things about Phoenix Laser, Inc.; that is the formal name of our partner’s company, and the Learn and Peters connection continues to thrive.

Doug Glenn: That’s great, that’s great. If anyone wants additional information on Laser Hard or Phoenix Laser, Inc., we can certainly get in touch with them.

I want to make sure people know a couple of names we’ve thrown out there, just for reference. Obviously, you’ve mentioned Jackie is your wife, and you’ve also mentioned Andy and Diana Wilkosz. Diana, of course, is your daughter, and Andy is now the plant manager/president.

Doug Peters: He is the president of the company.

Doug Glenn: Very good. A little kudos out again, back to the MTI relationship. Andy did a good bit of interning, I think, down at Texas Heat Treating, Inc. with Buster Crossley, if I remember correctly.

Doug Peters: That is correct. He worked out at Buster’s plant for three years before he came up.

Doug Glenn: Not that my opinion counts, but both Diana and Andy seem to be very accomplished folks; they represent Peters well in the industry.

Influential People (16:30)

You had mentioned, Doug, a couple of names that had a major influence or that were helpful to you, people that you want to maybe give some credit to. You mentioned about the guy at Talon. Is there anybody else, as you look back on your career, that has had a significant impact on you and helped you along the way?

Doug Peters: There have been so many people, I almost feel remiss in naming only a few names, in case I forget somebody. Obviously, Mr. Weller Gregg, who was that Talon guy (who was the head of heat treating), that gave me the start.

Source: Peters’ Heat Treating

My two dads. And my two moms. Jackie’s mom taught me one of the most valuable lessons in business that I tell people about and that I carry forward. Every Thursday, Jackie’s mom would watch our children, when they were young, so Jackie could come to the shop and do payroll. Then she started having us up for dinner after work.

I was up there one evening and she sensed that I was a little troubled with something, and she said, “You have something on your mind, today,” and I said, “Yeah, I have a few things going on at work,” and she said, “Well, might I suggest something? I have a question: Can you do anything about them, right now?” and I said, “Well, no,” and she said, “Well, I suggest that you worry about them when you can do something about them.”

It was absolutely the best piece of advice I ever got because I learned how to put some of those things on a shelf and deal with them when I could deal with them. I think it saved me a lot of grief and a lot of stress, over the years.

Obviously, Chet and Roger. They gave me the confidence to think that I was good enough to do this. Jim Balk, up at Hansen/Balk, was a real mentor, and he gave me the confidence that I was heading in the right direction, and we shared many of the same philosophies about how you take care of customers.

I’ll talk about Lance Miller who really put the love of the industry inside of me; I can’t say enough about Lance.

And then you look down through that long list of the notables in the industry: A shoutout to Roger Jones who’s going through a battle, right now, with cancer. Roger, we love you and we hope that everything comes through for you. John Hubbard, who’s a really good friend of mine and who was an industry giant with his career and his seat at Bodycote. Like I said, Jack Ross, and just the different people, Doug, that I’ve met over the years who were just phenomenal people.

MTI, right now, I believe, is in very capable hands with Tom Morrison and his staff. I feel very good to still be part of MTI.

Life Lessons (19:15)

Doug Glenn: Any lessons that you’ve learned, like the one that your mother-in-law gave you, which I think is a valuable one: “Don’t worry about it until you can do something about it.” Is there anything else that you’ve learned, as a “senior” in the industry, that you think is worth discussing?

Yes, I did just call you a senior!

Doug Peters: My parents stuffed a lesson right inside of me: be a finisher. Put all the tools away where you found them.

One of things from being in business that I can tell you is very valuable — when your name is on the sign, you accept all blame. I’ve never, in 44 years, ever thrown one of my employees under the bus to a customer. I accept the blame. Because, when something goes wrong in this building, it is something that I take responsibility for. You do not ever throw somebody under the bus; you go back and you work with them to perhaps correct the behavior, the execution, or something.

But that one’s been really important to me because, you know, you do not tear down a person’s dignity, as you work with them, whether it’s a customer or one of the folks that you work with inside of your building. So, that one has been very, very important to me.

Doug Glenn: As you’ve worked, over the years, I’m sure the way you started working, back when you were a young man and as you’ve progressed up through, were there any disciplines you developed that really helped make you either a better person or a better businessman, or anything of that sort — anything that maybe even you continue, to this day, in disciplines?

Doug Peters: Number one is being up really early in the mornings, when you have personal time. Because a lot of people complain that they don’t have personal time. They lose themselves in their vocation. My father was a big contributor to that. Dad used to go to work at 7:00 in the morning. He was a railroad engineer so he’d get up at like 4:30/4:45am. I said to him one day, “Dad, why do you do that?” And he looked at me and he grinned and he said, “Because you’re not!” The point was that that was his time.

“I think you have to make family time. I don’t care how busy you think you are; you have to be able to create that balance, and you have to force that balance to happen.”

Doug Peters, Founder & CEO, Peters’ Heat Treating

And I think you have to make family time. I don’t care how busy you think you are; you have to be able to create that balance, and you have to force that balance to happen. For instance, I was home every night by 5:30pm: I had dinner with my children, I played with them, we worked on homework, and when they were young, I’d help bathe them. And if I needed to go back to work, I would kiss Jackie and go back out the door after the kids were snugged in their beds.

Jackie, on the other hand, used to bring the kids to the shop. In the early days, I’d be working weekends, and she’d pack up a whole dinner and she’d come over and she’d bring the dog and the picnic table and be outside and we’d have a family dinner together. But I think, when we were together, we never really tried to not talk business because we always had our family first, business second, so that made that formula easy.

The only goal that we ever had for the company, Doug, was to be with our children when we wanted to be with them. When Diana graduated from college, I looked at Jackie and asked, “What’s the goal now?” and she said, “To be with our children when we want to be with them.” At that point, that’s been the only major goal that Jackie and I have ever had with Peters’ Heat Treating.

Learning Through Difficulties (22:37)

Doug Glenn: That’s great.

Well, you’ve addressed the other question I was going to ask you and that was about work/life balance.

Source: Peters’ Heat Treating

As you know, 40 some years, not every day is sunshine and roses — sometimes there can be difficult times. Can you recall a difficult time and — if you’re comfortable talking about it — what was it and what did you learn from it?

Doug Peters: Well, we’ve had two fires, one in each plant. Each fire was not a result of anything that was a delinquency on our part. But having to take each one of those buildings and sift through the rubble and to rebuild each one of them certainly was, I think, a character tester.

Losing key employees at the wrong time. All it did was reinforce why you do contingency planning, why you cross train, etc.

The one thing Jackie always said was it was wonderful being married to somebody that liked what he did for a living because I seldom came home, downtrodden. There were a lot of nights, in the early days of building the company, I’d be crawling into bed at 10:30pm when the phone would ring and 3rd shift would be calling off when we only had two guys up there, and I’d pull my pants back on and go back to work and then stay the whole next day. I did that numerous times as we built this company.

Those, somebody might say are “trials and tribulations,” but to me, it was just part of the job. It’s what I signed up to do and there’ll be no whining. You got your pants on, you went to work, and you were fortunate that you had a job to go to.

Career Highlights and Advice to the Next Generation (24:17)

Doug Glenn: Obviously, there were some valleys there, like the fires and things of that sort. How about the highlight? If you could pick one thing that was the highlight of your career, what would it be?

Doug Peters: There were a number of highlights: Watching the kids go through school and be successful in their respective careers, watching my wife be president of MTI in 2015 was a super, super highlight for me, and being fortunate to be asked to serve in the institute and to win the Heritage Award was something that was very special to me.

Here, in Meadville, we have what’s called the Winslow Award. It was started by Dr. Harry Winslow many, many years ago to go to the person that contributes the most to making sure that the Meadville economy is sound. I was the proud recipient of that in 2022. The list of names in that award, locally, is just amazing, too.

To not have made a bunch of enemies is something. You know, you have those instances where you’re in a difficult time — a job that’s gone bad or whatever. I’m very proud to say that, most of the time, when I see somebody that I haven’t seen in a while, I’m glad to see them and I think they’re glad to see me.

Doug Glenn: Last question for you, then: You and I both are getting up there as being “seniors” in the industry. Is there any piece of advice you would give to younger people?

Doug Peters: I think, first and foremost, don’t lose sight of who you are. I’ll go back to my father again. Dad looked at me one time and said, “Don’t become what your job is.” This all stemmed from him being a really beautiful woodworker. He could do woodworking that was gorgeous, and I asked him one time, “Why don’t you do this for a career?” and he said, “Well, it would be a job then!” And, in the course of that conversation, he looked at me and he said, “Don’t become what your job is. Be a great person that enjoys the job you chose.” I always tried to make sure that that’s who I was because I chose this vocation because I love to serve people, not because I loved to heat treat. It just so happened that heat treating was the vehicle that fulfilled my dream of serving people.

Dad was spot-on. Because, you know, when you retire, how many people do you see that are completely lost after they’ve walked out of their place of employment and they don’t know who they are? For me, that’s not been the case. I’ve been completely fulfilled. It was time. I’m happy to be on to the next stage in my life.

So, don’t become what your job is, is the first piece of advice I’m going to give these folks. Secondly, “Eat the frog.” Do the most unpleasant thing that you have to do every day, first, because your day is only going to get better. An MTI seminar that I went to gave me that piece of advice.

Last, but not least, take the three most important things you have to do tomorrow and write them down on a notebook and put them right in front of your computer at your desk at work so the next day when you walk in, there are only three things that are clouding your mind instead of list with 50 things. But if the day gets worse, turn the page, and write one down and take the other two off the list. It will help you focus and it will keep you moving forward.

Doug Glenn: That’s really good advice.

You know, you were talking about not becoming your job, which reminded me of a picture I saw of you, years ago, sitting behind a drum set. Tell us about that, just a little bit.

Doug Peters: I started playing the drums when I was in 8th grade. My father was a drummer, and he was a USO drummer. He was a sergeant in the Transport Corp, during World War II, in the European theater, and dad taught me how to play the drums. I did take some lessons, for a short time, but not as long as I would’ve liked to have.

Then, I had a rock band, and I’ve continued to play, over the years, and I play with artists on records. I’ve played, pretty much, my whole life, and I’ve enjoyed it.

Doug Glenn: That’s the human side and that’s great.

Doug, thanks very much. I appreciate the time you’ve taken to visit with us.

Doug Peters: Well, thank you, Doug. It’s always a pleasure.

About the Expert

Doug Peters with his wife, Jackie (Kuhn) Peters, founded Peters’ Heat Treating company in 1979. Over his career, Peters has served on numerous community service and industry trade association boards. He is past president of the NW Chapter National Tooling and Machining Association as well as the millennial president of the Metal Treating Institute.

Contact www.petersheattreat.com

Search Heat Treat Equipment And Service Providers On Heat Treat Buyers Guide.Com

Heat Treat Radio #106: Heat Treat Legend Doug Peters Read More »

We have the honor to speak with another

We have the honor to speak with another

The second, of course, is establishing, as you pointed out, The Heat Treat Doctor® brand. I’ll talk a little bit more on that later, perhaps.

The second, of course, is establishing, as you pointed out, The Heat Treat Doctor® brand. I’ll talk a little bit more on that later, perhaps.