CO2-Neutral Heat Generation Technology Progress

A new study from the Umweltbundesamt (the Federal Environment Agency in Germany) outlines a clear, technically grounded pathway for achieving CO2-neutral process heat across energy-intensive industries. This Technical Tuesday installment highlights the study’s key findings, offering North American heat treaters a concise look at the technical feasibility, economic pressures, and strategic choice involved in moving beyond fossil-fuel-based thermal processing.

This informative piece was first released in Heat Treat Today’s January 2026 Annual Technologies To Watch print edition.

Introduction

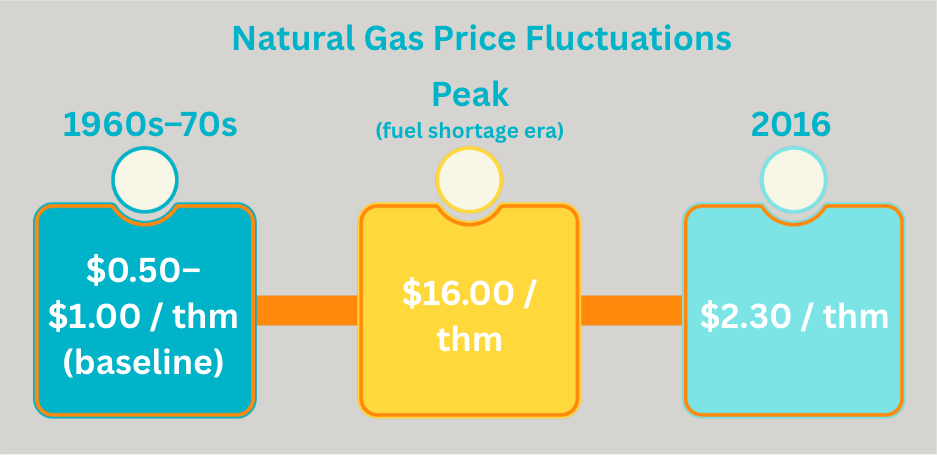

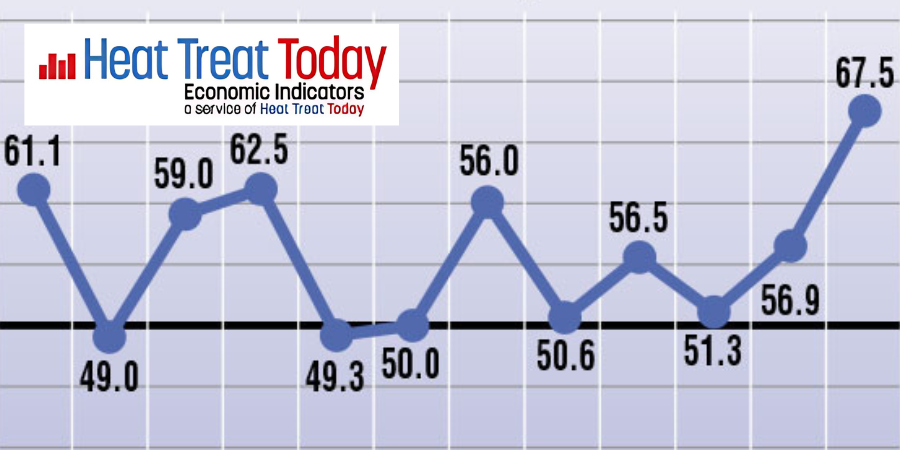

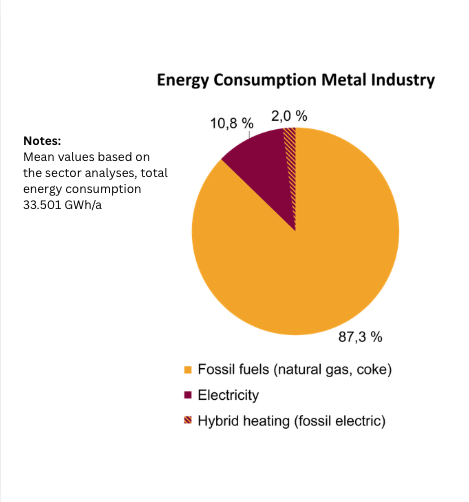

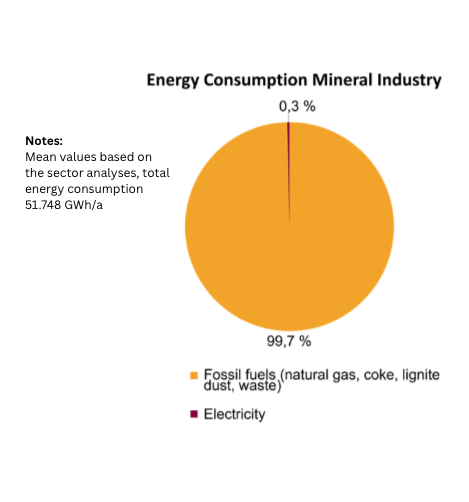

Efforts to mitigate climate change are crucial, particularly in Germany where there is a significant amount of energy-intensive industry, to achieve ambitious climate targets while preserving jobs and international competitiveness. Currently, process heat generation is heavily dependent on the use of fossil fuels, especially natural gas, with a low utilization of renewable energies. Fossil energy sources dominate the metal industry, accounting for 87.3%, while electricity represents 10.8%, and hybrid heating systems make up 2.0%. The mineral industry shows an even stronger dependence, with fossil fuels accounting for 99.7%. These figures illustrate the challenges and potential for technological innovations to provide CO2-free process heat in these sectors.

Although some sectors are already either using technologies for CO2-neutral process heat supply or are planning to do so, there is no comprehensive overview of the technical possibilities for generating process heat in energy-intensive industries in the context of future economic framework conditions.

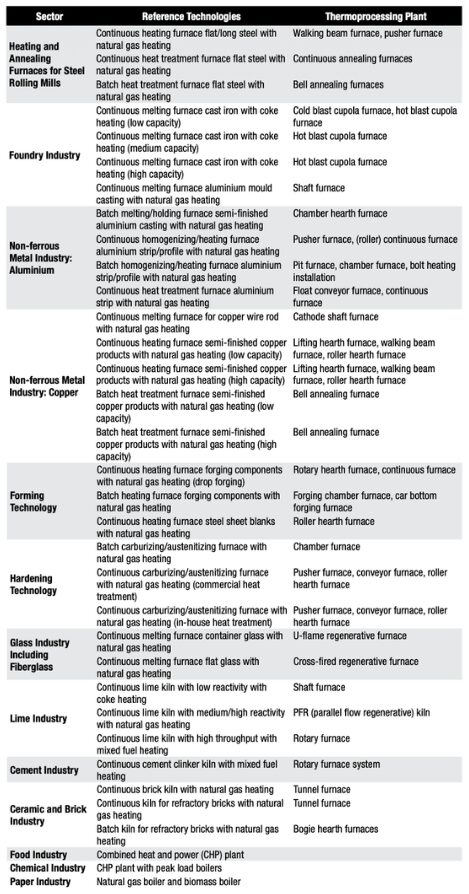

In this study, technologies for the CO2-neutral supply of process heat are considered from a technical, economic, and ecological perspective. The study was conducted for thirteen industries and thirty-four exemplary applications in the metals and minerals industries, as well as for the cross-cutting technology steam generation industry (Table A). For each application, alternative CO2-neutral technologies are examined for their technical feasibility, economic viability, and ecological impact. The focus is on the electrification of plant technology, the use of hydrogen, but also hybrid systems, and, in some cases, the use of biomass. From this comprehensive review of the current situation and the possible alternative technologies, findings and recommendations for implementation will be developed for industry, policymakers, and researchers to support the transformation to CO2-neutral process heat generation.

Study Method

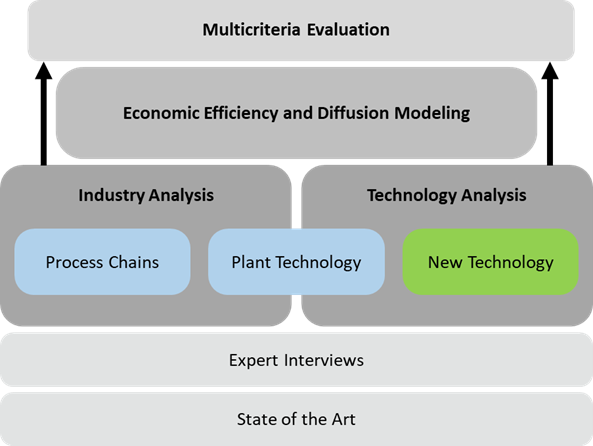

The study is based on an industry and technology assessment of the state of the technology (Figure 3). The results from the metal and mineral industries and the cross-sectional technology of steam generation were analyzed and summarized in consultation with experts. The central process chains were examined for each sector and the most important processes in terms of energy were identified. Each process chain contains several processes in which specific thermal process plants (industrial furnaces) are used, which are grouped into plant types. Based on the selected processes and plant types, applications are defined for further consideration. A reference technology and two to four CO2-neutral alternative technologies (new technologies) are assigned to each application. Key figures such as specific energy requirements, process-related emissions, or investment costs are used for comparison.

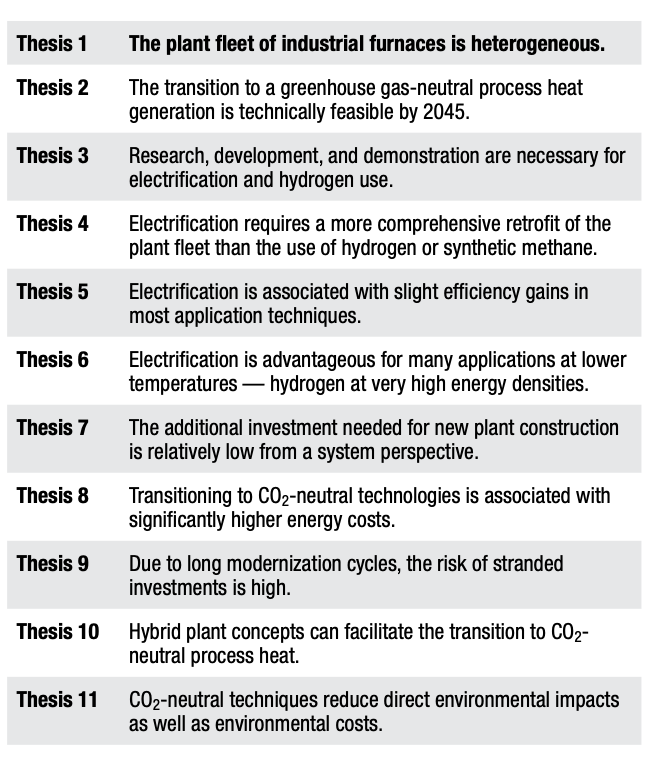

The central findings of the study are summarized in eleven theses on the transformation of process heat generation (Table B). In this article, Theses 1, 2, 6, and 9 are presented in detail, providing a broad overview of the essential findings. For a more in-depth examination of the theses, see the link to the original study.

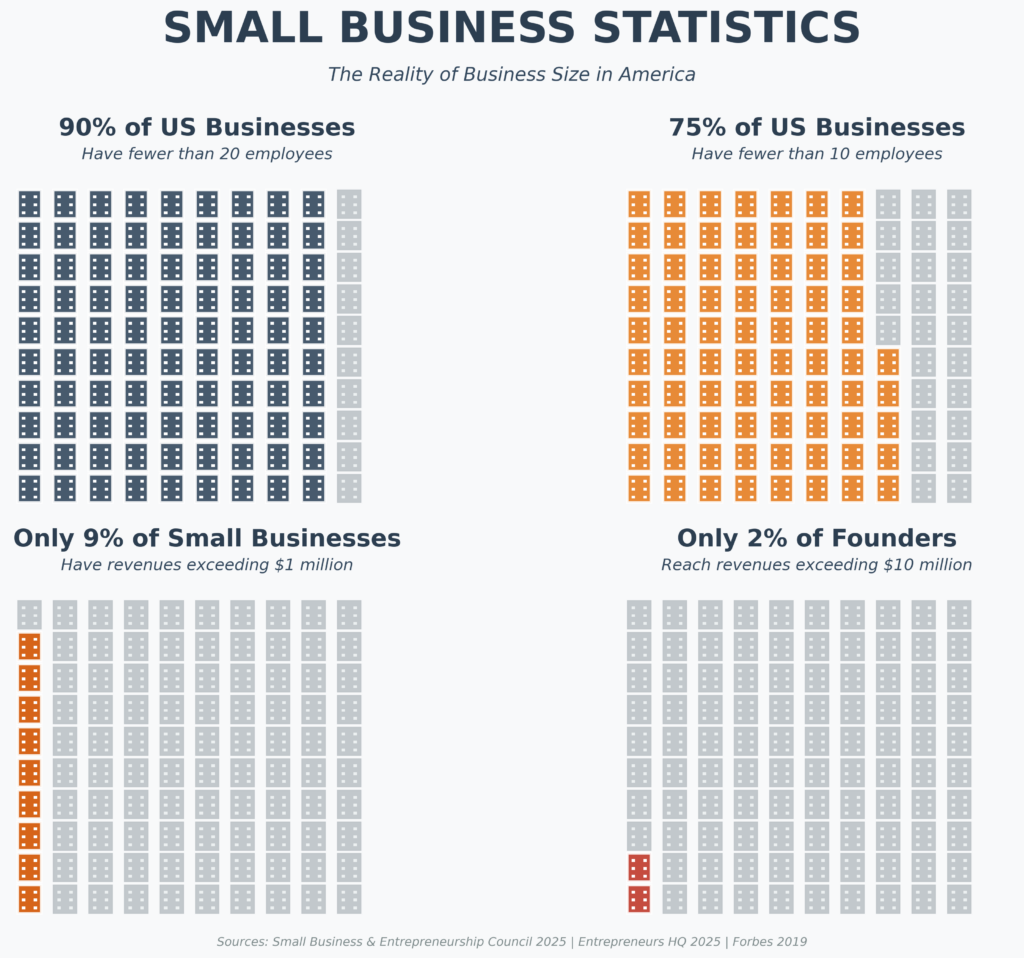

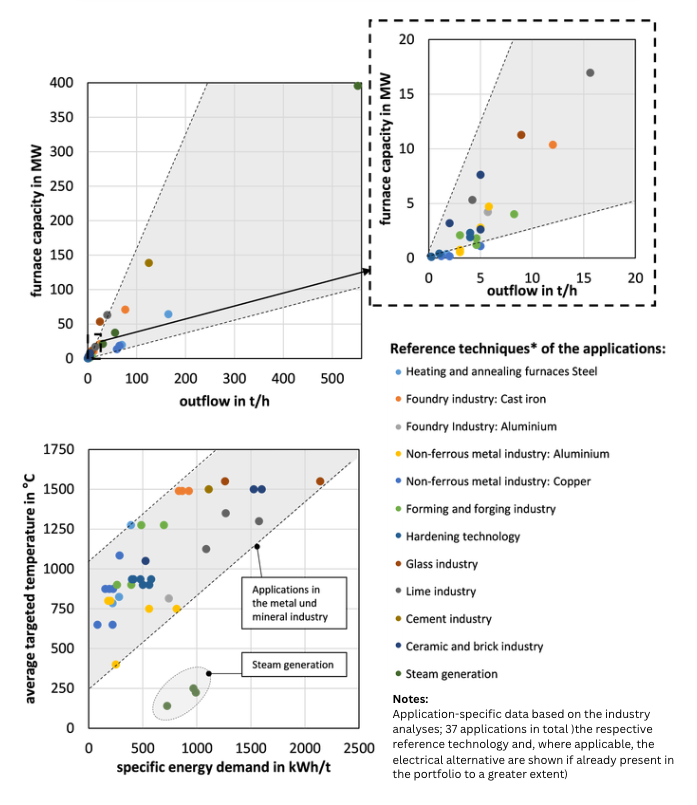

The Plant Fleet of Industrial Furnaces is Heterogeneous

The metal and mineral industries are characterized by numerous small process plants (throughput of less than 20 tons per hour and plant capacity of less than 20 MW). At the same time, there are large facilities with significantly higher throughput and corresponding higher plant capacities. Figure 4 shows a selection of technical examples from the study. Examples of large plants include heating and annealing furnaces in the steel industry with capacities of up to 170 tons per hour or cathode shaft furnaces in the copper industry with throughputs of up to 80 tons per hour. It is observed that the specific energy requirement of a plant correlates with the process temperature. The higher the required temperature of a process, the higher the specific energy requirement.

Additionally, the cross-sectional technology of steam generation was examined. The most up to date technology includes natural gas boilers or combined heat and power (CHP) systems. Industry-specific characteristics play a minor role in the selection of technology for achieving CO2 neutrality. The technical requirements for end applications are less different compared to industrial furnaces. This includes performance, throughput, pressure, and temperature.

A transition to CO2-neutral process heat generation encompasses various technical possibilities and obstacles, as well as investment costs and space requirements, depending on the industry and application. Accordingly, the necessary adaptation measures require a differentiated approach to the transition to CO2-neutral process heat generation. An effective strategy to achieve CO2 neutrality should take into account the unique characteristics of each industry’s production processes, as well as the specific challenges and opportunities they present.

Technical Transformation to CO2-Neutral Production is Feasible

Despite the wide variety of plants and specific challenges, the transition to CO2-neutral process heat generation is technically feasible by 2045. The solutions will vary depending on the industry and application, and the effort required to transition from currently used reference technologies to CO2-neutral alternatives varies significantly.

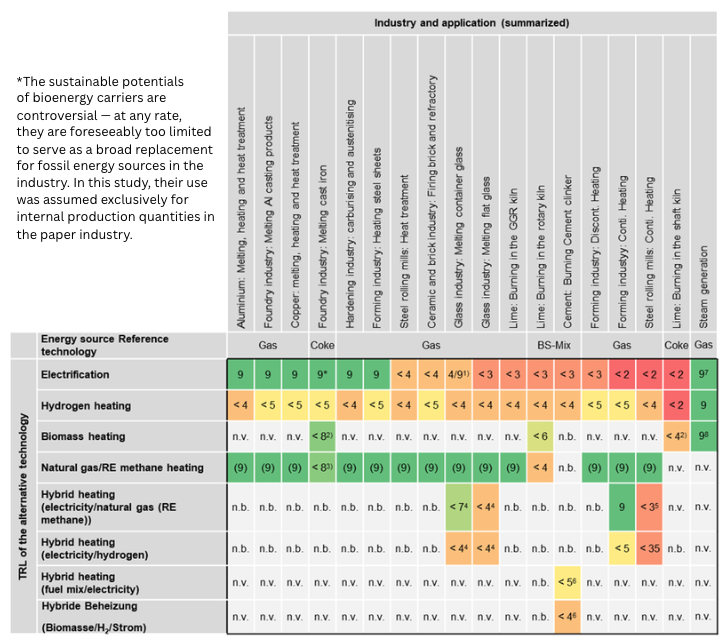

The heterogeneity of industrial furnaces has a significant impact on the feasibility of deploying CO2-neutral technology in the future. While electrification is already highly advanced and most up to date in applications such as the foundry industry, bulk forming, or melting of aluminium with induction furnaces, it shows comparatively low technological maturity in sectors like the lime and cement industry, which are associated with fundamental technical challenges; see Figure 5. This significant heterogeneity in the existing plant stock and terms of technology readiness level (TRL) (European Commission 2014) requires consideration in transformation strategies.

Both hydrogen and electrification can have a significant impact, although further research and development are needed in many areas. Across applications, it is evident that electrification generally requires the construction of new facilities. Transitioning from natural gas-operated reference technology to hydrogen involves less technical effort in terms of plant technology and can be accomplished by retrofitting the burner technology. Additionally, using hydrogen requires local infrastructure (pipes, valves) and its impacts on process and product quality need to be tested. Industrial-scale facilities are not yet available, resulting in a TRL of < 5, according to the study. However, with ongoing research and development in many projects, the TRL for many applications is expected to rise quickly in the coming years.

Scaling all alternative technologies to an industrial level and testing them in operational deployments are crucial. Some technologies face significant technical barriers, such as the continuous heating in steel rolling mills. These processes and their plant technology are characterized by very high process temperatures and production capacities, requiring heating technologies with a high energy density, which are not possible with current most cutting-edge electrical heating technologies. The use of hydrogen also presents a particular technological challenge, especially in areas where solid fuels like coke are currently used, such as in shaft kilns for lime burning or in cupola furnaces of iron foundries. As a result, alternative, bio-based fuels are being considered for these applications.

However, for these fuels to be a viable option, they need to be produced in sufficient quantity and quality. On the other hand, CO2-neutral techniques for steam generation using hydrogen and for electrification are already available for industrial use today.

The continuation of this article will be released in Heat Treat Today’s Sustainable Heat Treating Technologies edition (May 2026) where electrification versus hydrogen and a frank reckoning with the cost of new investments will be examined.

References

European Commission. 2014. Annex G – Technology Readiness Levels (TRL). Extract from Part 19 – Commission Decision C(2014)4995, “Horizon 2020 – Work Programme 2014–2015. General Annexes.” Brussels: European Commission.

Fleiter, Tobias, et al. 2023. CO2-Neutrale Prozesswärmeerzeugung: Umbau des industriellen Anlagenparks im Rahmen der Energiewende. Dessau-Roßlau: German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt).

All results in this article derive from the study “CO2-neutral process heat generation” (German: „CO2-neutrale Prozesswärmeerzeugung – Umbau des industriellen Anlagenparks im Rahmen der Energiewende: Ermittlung des aktuellen SdT und des weiteren Handlungsbedarfs zum Einsatz strombasierter Prozesswärmeanlagen”). The authors of this article would like to thank everyone who contributed to the study, listed in the published study. The study and further documents are on the website of the Federal Environment Agency in Germany (Umweltbundesamt).

This editorial is published with permission from Heat Treat Today’s media partner heat processing, which published this article in March 2024.

About The Authors:

Dr. Christian Schwotzer

Department for Industrial Furnaces and Heat Engineering

RWTH Aachen University, Germany

schwotzer@iob.rwth-aachen.de

Katharina Rothhöft, M.Sc.

Department for Industrial Furnaces and Heat Engineering

RWTH Aachen University, Germany

rothhoeft@iob.rwth-aachen.de

Dr. Tobias Fleiter

Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research

Karlsruhe, Germany

tobias.fleiter@isi.fraunhofer.de

Dr. Matthias Rehfeldt

Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research

Karlsruhe, Germany

matthias.rehfeldt@isi.fraunhofer.de

Dr. Fabian Jäger-Gildemeister

Federal Environment Agency of Germany (Umweltbundesamt)

Dessau-Roßlau, Germany

fabian.jaeger-gildemeister@uba.de

CO2-Neutral Heat Generation Technology Progress Read More »