Excess air plays multiple roles in heat treating systems. Learn about its importance in combustion and heat transfer, and why being well-informed will help your system run at peak performance.

This original content article, written by John Clarke, technical director at Helios Electric Corporation, appeared in Heat Treat Today’s Aerospace March 2021 print magazine. See this issue and others here.

Technical Director

Helios Electric Corporation

Source: Helios Electric Corporation

Is your system running optimally? The following discussion will provide a better, albeit abbreviated, understanding of the role of air in combustion and heat transfer.

Excess air in heating systems plays many roles: it provides adequate oxygen to prevent the formation of CO or soot, can reduce formation of NOx, increases the mass flow in convective furnaces to improve temperature uniformity, and at times, wastes energy. Excess air is neither good nor bad, but it is frequently necessary.

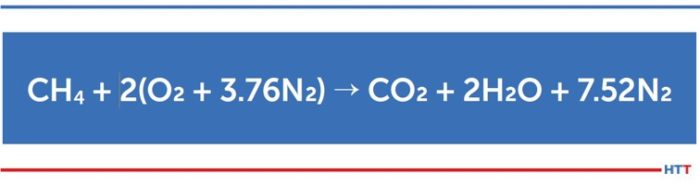

To begin, we must first look at a basic formula. For our discussions, we will replace natural gas, which is a mix of hydrocarbons with methane (CH4). The oxygen (O2) is supplied by air.

The above simplified formula describes perfect or stoichiometric combustion. The inputs are methane and air (where only the O2 is used to oxidize the carbon and hydrogen in the methane), and the products of combustion (POC) consist of heated carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O) and of course nitrogen (N2). (The actual reaction is far more complex and there are other elements present in air that we are ignoring for simplicity.) As we can see from the equation, the oxygen we need to burn the methane comes with a significant quantity of nitrogen.

In practice, it is very difficult to even approach this stoichiometric or perfect reaction because it would require perfect mixing, meaning that each molecule of methane is next to an oxygen molecule at just the right time. Without some excess air, we would expect some carbon monoxide and/or soot to be formed. Excess air is generally defined as the percent of total air supplied that is more than what is required for stoichiometric or perfect combustion. For natural gas, a good rule of thumb is to have about 10 cubic feet of air for every one cubic foot of fuel gas for perfect combustion. Higher air/fuel ratios, say 11:1, are another way of describing excess air.

In most heating applications, the creation of carbon monoxide and other unburnt hydrocarbons should be avoided, except in the rare cases where they serve to protect the material being processed. Employees must be protected from CO exposure; and soot can damage not only equipment, but the material being processed.

The amount of excess air that is required to find and combine with the methane is dependent not only on the burner, but also on the application and operating temperature as well. Some burners and systems can run with very little excess air (under 5%) and not form soot or CO. Others may require 15% or more to burn cleanly. Just because a burner performs well at 10% excess air in application A, does not necessarily mean the same level is adequate in application B.

Once the quantity of air exceeds what is needed to fully oxidize or burn the methane, combustion efficiency will fall because the added air contributes no useful O2 to the combustion process, and it must be heated. It is very much like someone putting a rock in your backpack before you set out for a 16-mile trek. Taking this analogy further, higher process temperatures equate to climbing a hill or mountain with that same rock — the higher the climb, or the higher the process temperature, the more energy you waste. Sometimes this added weight or mass can be useful.

The higher the excess air, the greater the mass flow. In other words, the total weight of the products of combustion goes up, and the temperature of the CO2, H2O, N2, and O2 goes down. If we are trying to transfer the heat convectively, this added mass or weight will provide improved heat transfer and temperature uniformity. A simple way to think of temperature uniformity is that the lower the temperature drop between the products of combustion and the material being heated, the better the temperature uniformity. Many heating systems are specifically designed to take advantage of this condition – higher levels of air at lower temperatures. This is especially true when convective heat transfer is the dominant means of moving heat from the POC to the material being heated (when the process temperature is roughly 1000°F or lower).

Some heating systems are specifically designed to operate as close to perfect combustion as is possible as the material is heated then switch to higher levels of excess air to increase the temperature uniformity as the setpoint temperature is approached. In other words, it provides efficient combustion when temperature uniformity is less of an issue and a very uniform environment as the material being processed nears its final setpoint temperature.

Of course, a system can be supplied with too much air, which can waste energy, but also prevent the system from ever reaching its setpoint temperature. The energy is insufficient to heat all the air, the material being processed, and compensate for furnace or oven loses. In these instances, it is obvious that we must reduce the air supplied to the system.

In indirect heating systems – where the products of combustion do not come in contact with the material being processed, like radiant tubes, for example — air in excess of what is required for clean combustion provides limited benefit and should generally be avoided. In these systems, it is best to play a game of limbo, “How Low Can You Go,” so to speak. Test each burner to see how much excess air is required to burn clean and add a little bit for safety. Remember, if you source your combustion air from outside in an area with significant seasonal variations, the blower efficiency will change, and seasonal combustion tuning is required.

Lastly, some burners require a minimum level of excess air to operate properly. This additional air prevents critical parts of the burner from overheating – or the air may limit the formation of oxides of nitrogen (NOx). In this application, altering the burner air/fuel ratio could generate excessive pollutants or even destroy the burner.

Efficiency is important, but the process is king. There is no magical air-to-fuel ratio and no single optimum level of excess air in the products of combustion. Each application is unique and must be thoughtfully analyzed before we can confidently say we have optimized our level of excess air. But careful attention paid to the effect that excess air has on your fuel-fired systems will pay dividends in improved safety and efficiency.

About the Author:

John Clarke, technical director at Helios Electric Corporation, a combustion consultancy, will be sharing his expertise as he navigates us through all things energy as it relates to heat treating equipment.