Ask the Heat Treat Doctor® has returned to bring sage advice to Heat Treat Today readers and to answer your questions about heat treating, brazing, sintering, and other types of thermal treatments as well as questions on metallurgy, equipment, and process-related issues.

This informative piece was first released in Heat Treat Today’s September 2025 People of Heat Treat print edition.

If you’ve ever experience internal cracking, surface blistering, loss of ductility, or high pressure hydrogen attack, today’s Technical Tuesday might contain just the information you need to avoid it. Read below to learn from Dan Herring as he addresses what hydrogen embrittlement is, how to avoid it, and what solutions should not be pursued in order to fix it.

The other night, The Doctor decided to relax and watch a rather whimsical movie, The Great Race (1965), directed by Blake Edwards, who is perhaps better known for directing Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Pink Panther. It is most memorable not for the actors, nor the plot, but for the infamous pie fight involving over 4,000 pies in a scene that took more than five days to film but lasted only four minutes on the big screen. Not one actor was spared the embarrassment of being hit by (multiple) pies in the face!

So, what does THIS have to do with heat treatment, you ask? Well, try as he may to believe the subject has been explained well in the past, The Doctor has been inundated recently with questions about hydrogen embrittlement (aka hydrogen-assisted cracking). Let’s learn more.

What Is It?

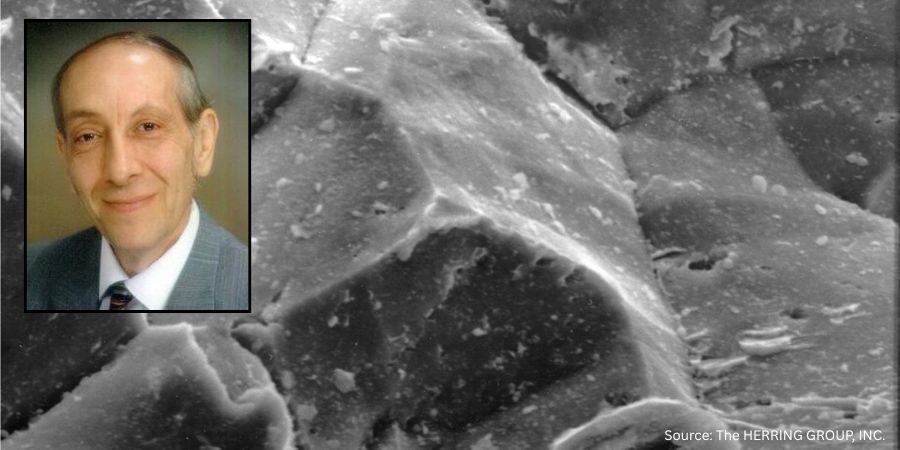

Hydrogen-assisted cracking (HAC) is an embrittlement phenomenon responsible for a surprising number of part cracking issues in heat treatment and is found to be the cause of many delayed field failures, especially if the components undergo secondary operations such as plating (Figure 1).

How Does Hydrogen Get In?

It is generally agreed that hydrogen in atomic form will enter and diffuse through a metal surface at elevated or ambient temperatures. The simple rule to remember about hydrogen is fast in, slow out. Once absorbed, atomic hydrogen often combines to form molecular hydrogen or other hydrogen molecules (e.g., methane). As these are too large to diffuse through the metal, pressure builds at crystallographic defects (e.g., dislocations and vacancies) and/or discontinuities (e.g., voids, laps/seams, inclusion/matrix interfaces) causing minute cracks to form. Whether this absorbed hydrogen causes immediate cracking or not is a complex interaction of material strength, external stresses, and temperature.

Most heat treaters associate hydrogen embrittlement with the plating process and the lack of a proper bake-out cycle. However, there are many other sources of hydrogen, including heat treating atmospheres; breakdown of organic lubricants left on parts; the steelmaking process (e.g., electric arc melting of damp scrap); dissociation of high-pressure hydrogen gas; arc welding (with damp electrodes); grinding (in a wet environment); and the end-use environment.

Parts undergoing electrochemical surface treatments, such as etching, pickling, phosphate coating, corrosion removal, paint stripping, and electroplating, are especially susceptible (Figure 2).

What Is The Nature and Effect of Hydrogen Attack?

Although the precise mechanism(s) is the subject of active investigation (Figure 3), the reality is that components fail due to HAC. It is generally believed that all steels above 30 HRC are vulnerable, as are materials such as copper, titanium and titanium alloys, nickel and nickel alloys, and the like. See Table A below for examples of hydrogen damage and ways to avoid it.

Since a metallurgical interaction occurs between atomic hydrogen and the atomic structure, the ability of the material to elastically deform or stretch under load is inhibited. Therefore, it becomes “brittle” under applied stress or load. As a result, the metal will break or fracture at a much lower load or stress levels than anticipated by designers. Since failures can be of a delayed nature, hydrogen embrittlement is insidious.

In general, as the strength of the steel goes up, so does its susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement. High strength steel, such as quenched and tempered steels (e.g., 4140, 4340), or precipitation hardened steels are particularly vulnerable. It is often called the Achilles heel of high strength ferrous steels and alloys.

Nonferrous Materials and Hydrogen Embrittlement

Nonferrous materials are also not immune to attack. Tough-pitch coppers and even oxygen-free coppers are subject to a loss of (tensile) ductility when exposed to reducing atmospheres. Bright annealing in hydrogen bearing furnace atmospheres or torch/furnace brazing are typical processes that can induce embrittlement of these materials.

In copper, the process involves diffusion and subsequent reduction of cuprous oxide (Cu₂O) to produce water vapor and pure copper. An embrittled copper often can be identified by a characteristic surface blistering resulting from expansion of water vapor in voids near the surface. Purchasing oxygen-free copper is no guarantee against the occurrence of hydrogen embrittlement, but the degree of embrittlement will depend on the amount of oxygen present. For example, CDA 101 (oxygen free electronic) allows up to 5 ppm oxygen while CDA 102 (OFHC) permits up to 10 ppm. A simple bend test is often used to detect the presence of hydrogen embrittlement. Metallographic techniques can also be used to look at the near surface and for the presence of voids at grain boundaries.

Are Low Hydrogen Concentrations Also Problematic?

Of concern today is embrittlement from very small quantities of hydrogen where traditional loss-of-ductility bend tests cannot detect the condition. This atomic level embrittlement manifests itself at levels as low as 10 ppm of hydrogen — in certain plating applications it has been reported that 1 ppm of hydrogen is problematic! Although difficult to comprehend, numerous documented cases of embrittlement failures with hydrogen levels this low are known.

This type of embrittlement occurs when hydrogen is concentrated or absorbed in certain areas of metallurgical instability. This concentrating action occurs via either residual or applied stress, which tends to “sweep” through the atomic structure, moving the infiltrated hydrogen atoms along with it. These concentrated areas of atomic hydrogen can coalesce into molecular type hydrogen, resulting in the formation of high localized partial pressures of the actual gas.

How Does Hydrogen Get Out?

Hydrogen absorption need not be a permanent condition. If cracking does not occur and the environmental conditions are changed so that no hydrogen is generated on the surface of the metal, the hydrogen can re-diffuse out of the steel, and ductility is restored. Performing an embrittlement relief cycle, or hydrogen bake-out cycle (the term “bake-out” is misleading as the process involves both inward diffusion and outgassing), is a powerful method in eliminating hydrogen before damage can occur. Key variables are temperature, time at temperature, and concentration gradient (atom movement).

Electroplating, for example, provides a source of hydrogen during the cleaning and pickling cycles, but by far the most significant source is cathodic inefficiency. To eliminate concerns, bake-out cycles and recommended temperatures/times are shown in ASTM B850-98 (latest revision) as a function of steel tensile strength (see Table 1 of the specification). However, in this writer’s eyes, a “bake-out” cycle of at least 24 hours at temperature is required for the effective elimination of hydrogen as a concern regardless of the tensile strength of the material. Also, caution should be exhibited to prevent over-tempering or softening of the steel, especially on a carburized, or induction hardened part.

Next time we will talk about quench and temper embrittlement, as well as embrittlement due to overheating during forging, all of which are often mistaken for hydrogen embrittlement.

References

ASTM International. 2022. ASTM B850-98 (Reapproved 2022), Standard Guide for Treatments of Steel for Reducing the Risk of Hydrogen Embrittlement. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International. https://www.astm.org.

Herring, D. H. 2004. “A Heat Treater’s Guide to Hydrogen Embrittlement.” Industrial Heating, October.

Herring, D. H. 2006. “The Embrittlement Phenomena in Hardened & Tempered Steels.” Industrial Heating, October.

Herring, D. H. 2014–2015. Atmosphere Heat Treatment, Volumes I & II. Troy, MI: BNP Media.

Krause, George. 2005. Steels: Processing, Structure, and Performance. Materials Park, OH: ASM International.

About the Author

“The Heat Treat Doctor”

The HERRING GROUP, Inc.

Dan Herring has been in the industry for over 50 years and has gained vast experience in fields that include materials science, engineering, metallurgy, new product research, and many other areas. He is the author of six books and over 700 technical articles.

For more information: Contact Dan at dherring@heat-treat-doctor.com.

For more information about Dan’s books: see his page at the Heat Treat Store.