Insufficient austenitizing affects far more than final hardness. It disrupts phase transformation, weakens mechanical performance, and increases the risk of distortion or failure in demanding service conditions. In this Technical Tuesday installment, Ana Laura Hernández Sustaita, founder of Consultoría Carnegie, explains the metallurgical origins of incomplete austenite formation, how furnace uniformity, heating rate, steel chemistry, and part geometry contribute to the problem, and modern process-control and simulation strategies that ensure full transformation and repeatable, high-quality results.

This informative piece was first released in Heat Treat Today’s January 2026 Annual Technologies To Watch print edition.

Para leer el artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

Introduction

When a steel part is insufficiently austenitized, it is commonly referred to as underhardening, the resulting loss of hardness after quenching. However, in this article, we will extend the discussion beyond hardness alone, exploring the phenomenon of insufficient austenitizing, analyzing its causes and direct influence on microstructure and mechanical properties, and discussing modern strategies to prevent it.

The Role of Austenitizing in Heat Treatment

The main purpose of heat treatment is to produce a homogeneous or a desired mixed microstructure that ensures the required mechanical properties for the intended service conditions: tensile strength, impact resistance, yield strength, etc. Austenitizing is the first critical step for many processes. It involves heating the steel above the A3 temperature (typically 30–50°C or 85–120°F higher) to transform its microstructure into a face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice for a certain period of time. This step resets the steel’s structural history, particularly after casting, forging, or rolling, and defines the baseline for subsequent quenching and tempering operations.

What Is Insufficient Austenitizing?

Austenite formation involves structural and compositional changes influenced by the initial microstructure and the steel’s chemical composition. When austenitizing parameters are not properly established, such as insufficient temperature, inadequate soaking time, or poor furnace performance (e.g., lack of thermal uniformity), the transformation remains incomplete. The result is a microstructure containing undesired residual phases that compromise hardness, dimensional stability, and mechanical strength. Therefore, any microstructure that fails to fully transform to austenite due to these factors can be directly associated with insufficient austenitizing.

Common causes of insufficient austentizing include:

- Inadequate austenitizing temperature: Ferrite and carbides do not fully dissolve if the temperature is too low.

- Insufficient holding time: A short soak time prevents uniform carbon diffusion throughout the austenite.

- Thermal non-uniformity in the furnace (cold zones): This leads to regions with different degrees of transformations.

- Chemical composition of the steel: Alloying elements modify diffusion kinetics and impact the critical transformation temperatures.

- Geometry and dimensions of the part: Larger cross-sections require longer soak times for full heat diffusivity.

- Rapid heating rates: Excessive heating, especially during induction hardening, can result in structural inhomogeneity and incomplete transformation.

Effects of Insufficient Austentizing

Heterogeneous Microstructure

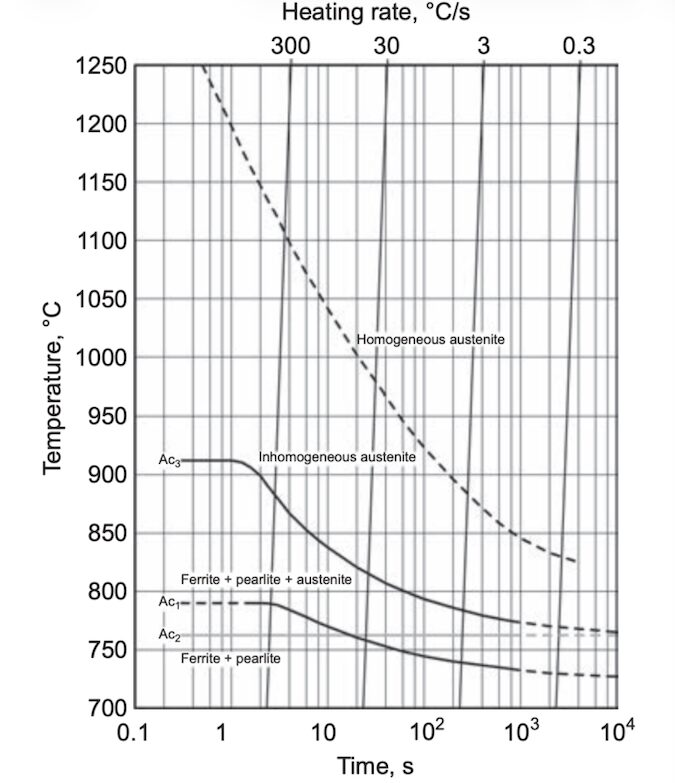

As illustrated in the ASM Handbook, Volume 4A: Steel Heat Treating Fundamentals and Processes (2013), the kinetics of austenite formation depend strongly on the heating rate. At lower heating rates, diffusion-driven homogenization occurs at relatively lower temperatures, whereas rapid heating produces microstructural heterogeneity, an effect that is especially critical in induction or direct-flame heating. In other words, insufficient austenitizing is more likely to occur when high heating rates are used.

Consequently, a microstructure with heterogeneous composition leads to variations in the martensite transformation temperatures (Ms and Mf) throughout the part. During quenching, regions with lower carbon content transform earlier, producing softer martensite, while areas with higher carbon content transform at lower temperatures, resulting in internal stresses and an overall inconsistent microstructure.

Risk of Distortion and Premature Failure

The transformation from BCC or BCT to FCC (Defined: BCC: body-centered cubic; BCT: body-centered tetragonal; FCC: face-centered cubic) lattice during austenitizing involves a specific volume change. If this transformation occurs unevenly, differential expansion generates internal stresses, distortion, and in severe cases, microcracks. Rapid heating or poor furnace convection exacerbates these effects by producing steep temperature gradients across the part.

Reduced Hardness and Mechanical Strength

Incomplete transformation leaves undissolved carbides and residual ferrite, reducing hardenability and the amount of carbon in solid solution. This limits the formation of martensite during quenching and lowers final hardness and strength.

Increased Brittleness and Lower Toughness

A mixed structure of ferrite, pearlite, partial martensite, and retained austenite results in mechanical anisotropy and reduced energy absorption under impact loading. This condition increases the risk of brittle fracture, particularly in high-stress or cyclic applications.

How to Prevent Insufficient Austenitizing

Accurate Furnace Control

Consultoría Carnegie

To ensure proper process control during the soaking stage, it is essential to use calibrated thermocouples strategically positioned inside the furnace to obtain accurate temperature measurements. Regular calibration prevents temperature reading errors and directly contributes to heat treatment quality. It is also important to get advice from an expert to determine the recommended service life of the thermocouples. Maintaining proper traceability and replacing them at the appropriate intervals ensures optimal system performance.

Additionally, the use of internal circulation fans in convection furnaces helps maintain thermal uniformity, preventing the formation of hot or cold zones.

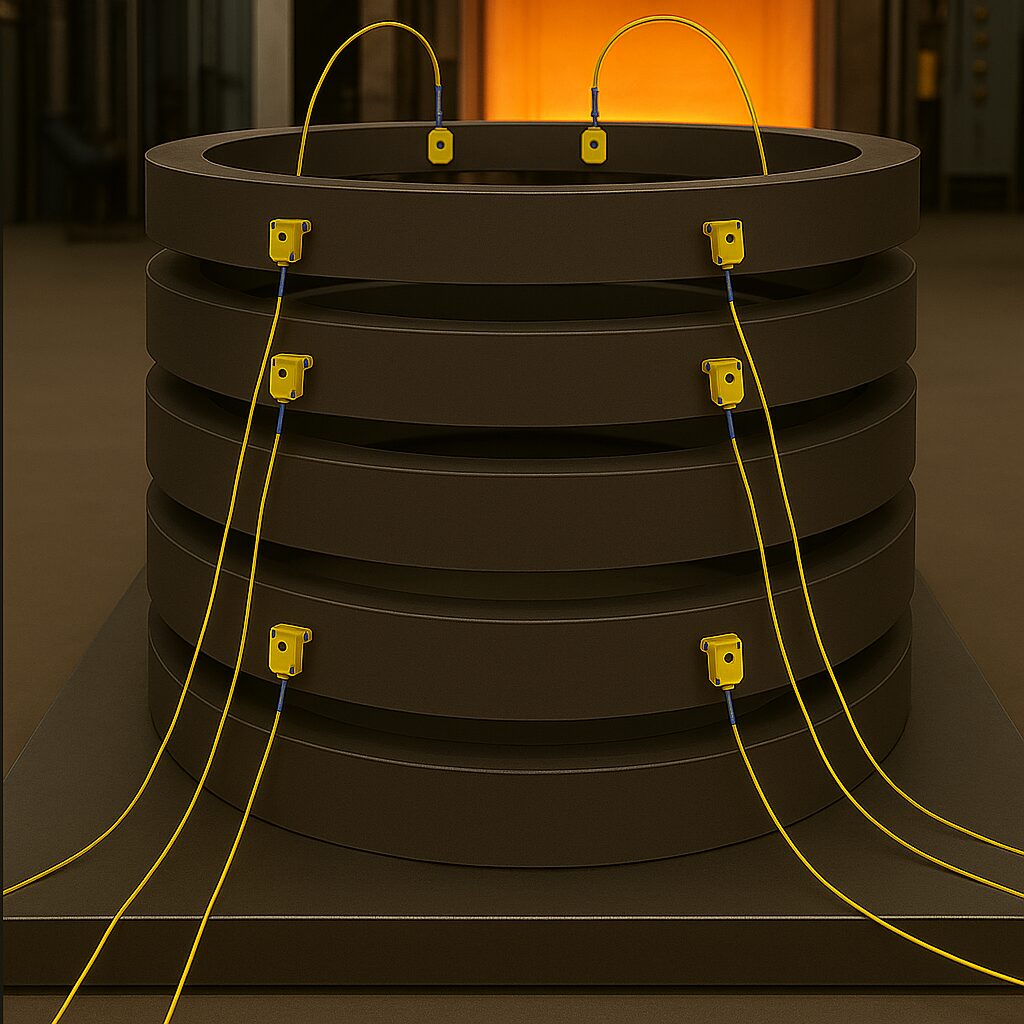

Another method to monitor and control process temperature is using temperature data loggers. These devices, which are connected to contact thermocouples and placed directly on the parts, are especially recommended for components with complex geometries or large cross-sections. They record real-time temperature data throughout the process, allowing verification that no transient fluctuations occur during the soaking period.

Accurate Loading Distribution

For loads where heat treatment must be applied to a significant number of parts, it is recommended that a study be conducted to determine the maximum stacking height that will ensure proper heat flow and uniform heating. A preliminary assessment can be performed by strategically placing thermocouples in different locations and on different parts, for example, on the first part in the load, one in the middle section, and another at the bottom of the stacking tower.

Once the parts enter the process, their heating behavior can be monitored to verify that the soaking time is sufficient for all pieces in the stack to complete their transformation upon reaching the target temperature or to determine whether adjustments to the loading configuration are necessary.

Use of Thermodynamic Simulation to Optimize Process Parameters

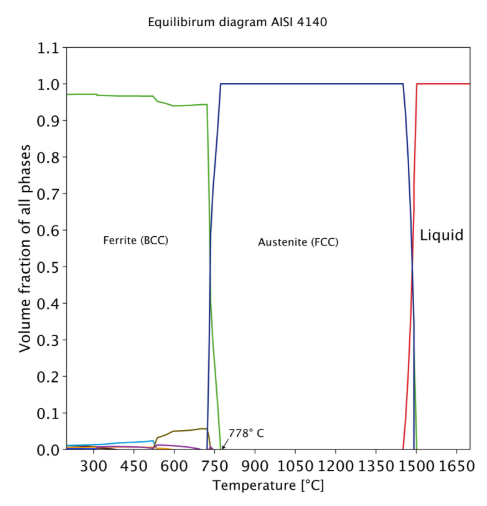

Each steel grade has an optimum austenitizing temperature in function of its chemical composition. For carbon steels (10XX series), these temperatures can be estimated using the Fe–C diagram; however, once alloying elements are added, this diagram is no longer sufficient. In such cases, it becomes necessary to rely on critical temperature calculations or on more advanced tools such as thermodynamic simulations using specialized software, like Thermo-Calc®.

Although the ideal scenario would be to heat treat each material at its specific optimum temperature, this approach is impractical in industrial production; the required processing of each part individually would slow the manufacturing line and increasing resource consumption, including time and fuel.

Thermodynamic tools such as Thermo-Calc allow engineers to evaluate how variations in chemical composition (arising from casting tolerances or adjustments in alloying elements) affect transformation temperatures. This enables the selection of an optimum processing temperature that ensures complete austenitization for all possible compositional variations within the specification. As a result, the heat treatment operation becomes more robust, more reproducible, and more energy efficient.

For example, in Figure 3, if a 4140 steel is heated only to 750°C (1380°F) instead of 850°C (1560°F), the ferrite will not fully dissolve. As a result, the microstructure will consist of soft martensite and residual ferrite after quenching, rather than a fully homogeneous and hard martensitic structure. This significantly reduces the material’s hardness and mechanical strength.

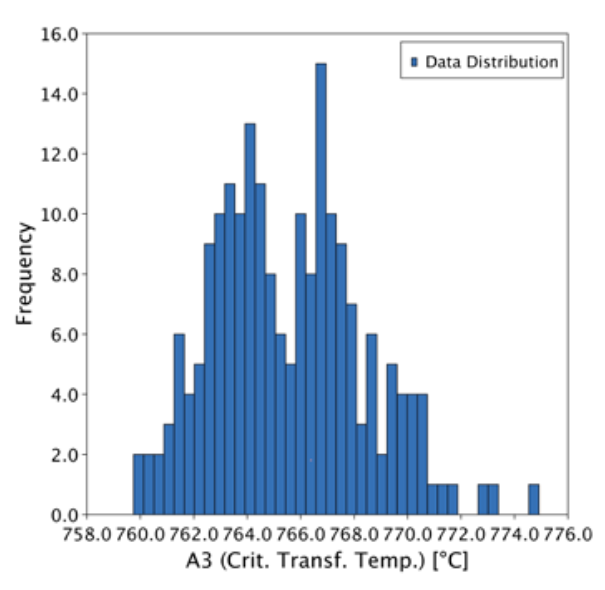

We can observe in the histogram (Figure 4) that even within the same steel grade, the A3 temperature can vary from approximately 760−776°C (1400−1429°F) solely due to the composition tolerances specified for the alloy. If we also consider the presence of residual or microalloying elements, it becomes clear that we cannot expect identical behavior during heat treatment or identical mechanical properties across all heats.

In such cases, thermodynamic tools allow us to evaluate a batch of possible chemistries and determine an optimal austenitizing temperature that is suitable for all compositional variations.

Heating Curve Design

To ensure that transformation temperatures are reached uniformly (whether in processes involving large loads or parts with variable geometries), it is advisable to implement controlled heating rates. Although this approach may increase processing time, the benefits include reduced distortion risk and assurance of complete austenitic transformation.

The key is to design an appropriate time–temperature profile, which depends on factors such as part dimensions and material properties, including thermal diffusivity, heat capacity, density, and thermal conductivity.

Conclusion

Insufficient austenitizing, also known as underhardening, represents far more than a loss of hardness. It is a metallurgical deficiency that affects microstructural homogeneity, dimensional stability, and mechanical performance. Through rigorous control of temperature, time, and furnace uniformity combined with modern simulation tools, engineers can ensure reliable transformations, minimize distortion, and achieve consistent high-quality results in steel heat treatment.

References

ASM International. 2013. ASM Handbook. Vol. 4A: Steel Heat Treating Fundamentals and Processes.

Callister, W. D. 2019. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Herring, Dan. Metallurgical Fundamentals of Heat Treatment. Industrial Heating.

Krauss, G. 1980. Principles of Heat Treatment of Steel. ASM International.

Nuñez González, G. 1990. Fallas en los Tratamientos Térmicos para Aceros Herramienta.

Thomas, L. 2018. “Austenitizing Part 2: Effects on Properties.” Knife Steel Nerds. https://knifesteelnerds.com/2018/03/01/austenitizing-part-2-effects-on-properties/.

Totten, G. E. 2007. Steel Heat Treatment: Metallurgy and Technologies. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

About The Author:

Founder

Consultoría Carnegie

Ana Laura Hernández Sustaita holds a Master’s degree in Materials Science and engineering. She is the founder of Consultoría Carnegie, a technical consulting and training firm specializing in steel heat treatment in Mexico. Additionally, she works as a technical support engineer at Thermo-Calc Software, providing assistance to clients across México, Canada, and United States of America. Ana actively promotes metallurgical education throughout Latin America and advocates for the integration of computational tools into industrial heat treatment practice.

For more information: Contact Ana Hernández at anahdz@consultoriacarnegie.com.