Heat resistant alloys used for heat treating fixtures, muffles, retorts, radiant tubes, and other parts are typically stainless steel or nickel based austenitic alloys. Welding of these alloys requires practices that are often exactly the opposite of the practices required for carbon and alloys steels since austenitic stainless steels do not undergo phase transformations. Metallurgists are often asked many questions on the proper welding methods. Carbon and alloy steel welding requires practices and procedures that will minimize or prevent the chances of cracking due to potential martensite formation during weld solidification. Austenitic stainless steels do not undergo any phase transformation. They require rapid cooling to prevent solidification cracks due to hot cracking. Thus different procedures are required.

In this Heat Treat Today Technical Tuesday feature, Marc Glasser, Director of Metallurgical Services for Rolled Alloys, provides some basic information on the metallurgy as well as good welding practices to follow.

In this Heat Treat Today Technical Tuesday feature, Marc Glasser, Director of Metallurgical Services for Rolled Alloys, provides some basic information on the metallurgy as well as good welding practices to follow.

Reprinted with permission from Heat Treat 2019: Proceedings of the 30th Heat Treating Society Conference and Exposition, October 15-17, 2019, Detroit, Michigan, USA. ASM International, 2019.

CHEMISTRY CONSIDERATIONS

Most heat resistant alloys used in the heat treating industry for components are austenitic. They can be austenitic stainless steels, or austenitic nickel alloys. The key word is austenitic. One of the virtues of austenitic materials is that they are not subject of phase changes from cooling to heating or heating to cooling. This is markedly different from alloy and carbon steels, which undergo a phase transformation from austenite to ferrite and cementite. The cooling must be slow enough to prevent martensite formation, so preheating and postheating are performed to either prevent this phase transformation or to temper any formed martensite.

Austenitic alloys do not undergo phase transformations to martensite, and as a result slow cooling the material is the worst operation that an austenitic alloy can be subject to. In austenitic alloys, the main concern is the tendency for welds to hot tear upon solidification[1]. In stainless steels with up to approximately 15% nickel, the solution is simple. The composition is adjusted to form small amounts of ferrite during solidification[2]. Prediction of the ferrite number FN, which represents an estimate of the amount of ferrite in the weld after solidification, is predicted by using Schaeffler diagrams. The ferrite nullifies the effect of certain trace elements that cause hot cracking [1]. One of these trace elements, phosphorous cannot be refined out of the material. Since these materials are all melted from scrap metal, the amount of phosphorous found in the heat will mirror the amount in the scrap. Sulfur, silicion, and boron also contribute to hot shortness, but these elements can be refined to very low levels in the steelmaking process.

For higher nickel bearing grades, with more than 20% nickel, the chemistry precludes the possibility of ferrite formation. Therefore, other means must be employed to prevent hot tearing during solidification. In this case, the residual trace elements, particularly P must be kept low, as they lead to hot shortness [2, 3]. Certain alloy additions including manganese (Mn), niobium (Nb), molybdenum (Mo), and carbon (C) all reduce the propensity of austenitic nickel alloys and high nickel stainless steels to crack [4]. 310 stainless steel stans in a unique position having neither ferrite formers nor weldability-enhancing alloy additions. In this alloy, control of chemistry and residuals is of utmost importance.

The other key to successful welding of nickel alloys is to minimize the time spent in the high temperature range where they are susceptible to hot tearing [4].

GOOD WELDING PRACTICES

Good welding practices for nickel alloys are centered on the need to remove heat as quickly as possible in order to minimize the time spent in the hot tearing range. The first consideration is to keep the heat input as low as possible to still get a full penetration weld. The actual input in kJ is dependent on the alloy being welded.

Heat input (HI) is defined as: HI (KJ/in) = Voltage x Amperage x 6/(Speed (inch/min) x 100)

Welds should NOT be preheated and interpass temperatures should be 200°F maximum. The cooler the interpass temperature is, the less likely hot tearing is [5]. A reliable, easy test for a welder is the spit test. Spit on the weld, and if it boils it is still to hot, and further waiting is in order.

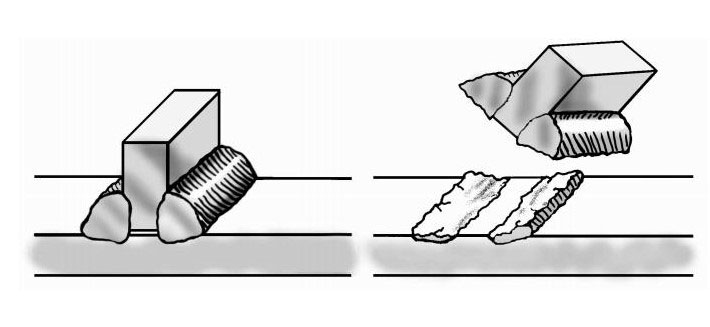

One of the most important considerations in welding nickel alloys is to weld in a straight line along the length of the weld and do not weave. Welders tend to weave from side to side especially when welding nickel alloys which are more viscous that carbon steels and this weaving makes the metal flow better. While this technique works well for carbon steel where a higher heat input and slower cooling are necessary, it is exactly the wrong procedure for nickel alloys. Weaving tends to flatten out a weld. This in turn reduces the crown height and strength.

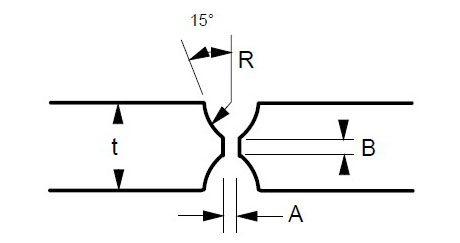

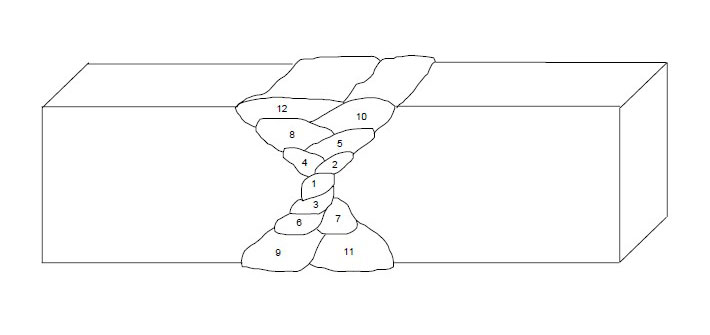

Furthermore, weaving tends to increase the heat going into the weld and slow down the weld speed. The key is to get a nicely shaped, convex weld bead, as illustrated in Figure 1. A concave bead configuration tends to crack along the centerline [5].

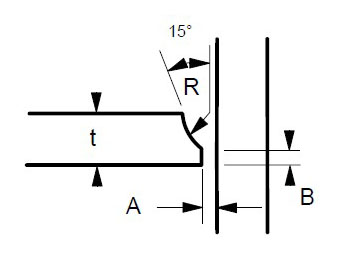

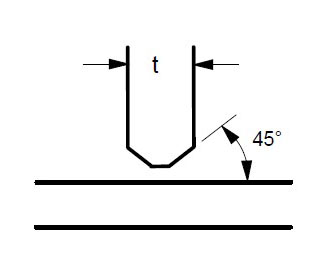

Full penetration welds are important. Beveling one or more of the pieces to be joined may be required to get a full penetration weld. Incomplete penetration leaves a void between the two workpieces. Such a channel can entrap surface treating gases leading to brittle pieces surrounding the weld. Furthermore, the gap can act as a propagation site for cracks which form from thermal cycling from heat treating. This is shown in Figure 2 below.

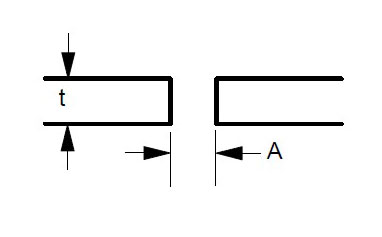

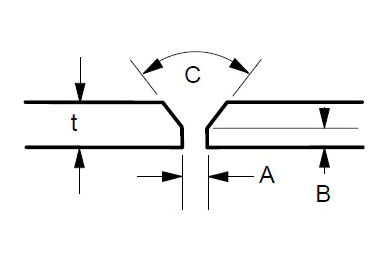

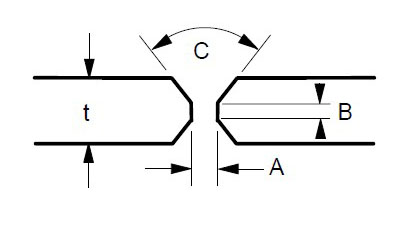

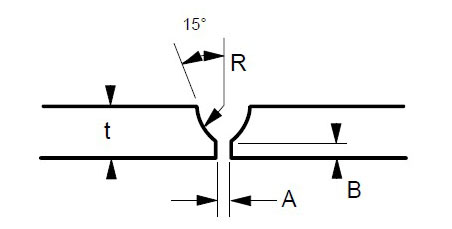

Some suggested joint designs include square butt joint, single V joint, double V joint, single U joint, double U joint, J groove joint, and T Joint. These are shown in Figures 3 to 9 below, along with design criteria. These suggestion grooves are from ASME code[6], but are good guidelines to follow even if code stamps are not required.

t = greater than 1/4″

For joints requiring maximum penetration. Full penetration welds give maximum strength and avoid potential crevices.

Regardless of which joint is selected, the purpose is to obtain a full penetration weld with no voids or channels, as shown in Figure 10 below.

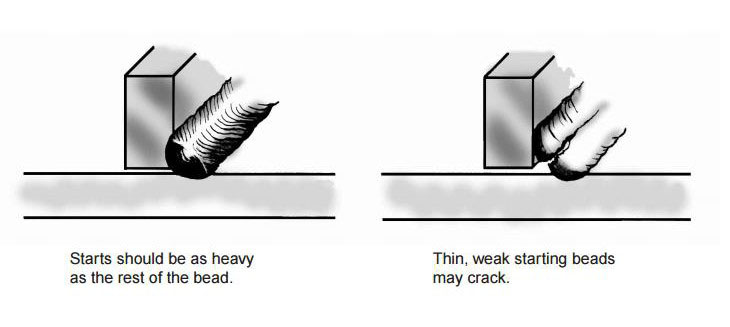

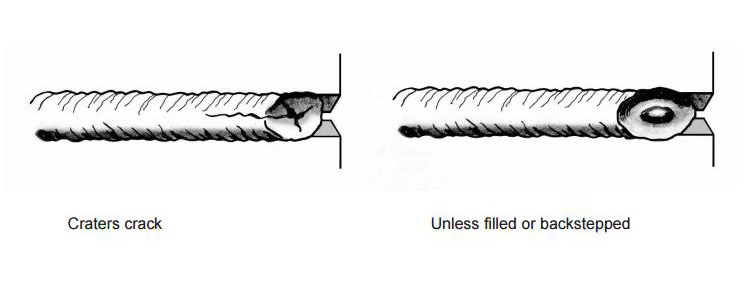

Both the starting and finishing ends of the weld beads can be crack initiation sites. The best practice for starting is to make the start of the weld bead as heavy as the rest of the weld bead [4]. A light or thin start up can cause cracking. This is shown in Figure 11. Furthermore, in nickel alloys, the end of the bead can sometimes yield a star shaped crack. This can be eliminated by backstepping the weld for ½ to 1 inch as shown in Figure 12 [3].

Cleanliness is extremely important for welding stainless and nickel alloys. Some general rules include [5]:

- Remove all shop dirt, oil, grease, cutting fluids, lubricants, etc. from welding surface and on the area 2 inches wide on each side of the weld joint with suitable cleaning agent.

- Eliminate all sources of low melting metal contaminants from paints, markers, dies, back up bars, etc. Chromium plate copper back up bars can form a barrier between copper and the weld surface. Copper can cause HAZ cracking in nickel alloys. These low melting contaminants cause cracking and failures in nickel alloy and stainless steel welds. Avoid using lead or copper hammers in fabrication shops.

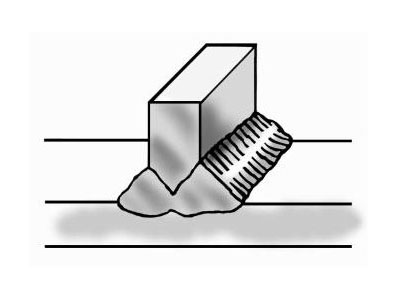

- Grind clean the surfaces and the HAZ areas. Chromium scales melt at higher temperatures than the base metals and will not be reduced by filler metals.

- When welding to nickel alloy or stainless to plain carbon steel, the plain carbon steel must be ground on both sides too.

SHIELDING GASES

Bare wire welding requires a shielding gas to protect the weld from oxidation, loss of some elements to slag or oxide formation, and contamination.

Most stainless steel and nickel alloys require 100% argon for shielding for the GTAW or TIG process.

GMAW or MIG welding has two distinct modes of metal transfer. Spray arc processing transfers metal between wire tip and workpiece as droplets. Short circuit processing transfers the metal in sheets or globules. The most common shielding gas for spray arc GMAW welding is 100% argon. 10-20% helium can be added along with small amounts of carbon dioxide (1% max) to improve bead contour and reduce arc wander [1]. Short circuit GMAW welding uses blends of inert gases usually either 75% argon – 25% helium or 90% helium – 7.5% argon – 2.5% carbon dioxide.

In order to prevent hot cracking with the GMAW process, 602CA® requires a unique blend of 90% argon – 5% helium – 5% nitrogen and a trace (0.05%) carbon dioxide. This blend was trademarked as Linde CRONIGON® Ni30. It is not readily available but there are other close alternate quad gas blends that are commercially available. For GTAW welding, argon with 2.5% nitrogen is used to prevent cracking in 602CA. The nitrogen is the key to preventing cracking in 602CA regardless of method.

RESTRAINT AND DISTORTION CONTROL

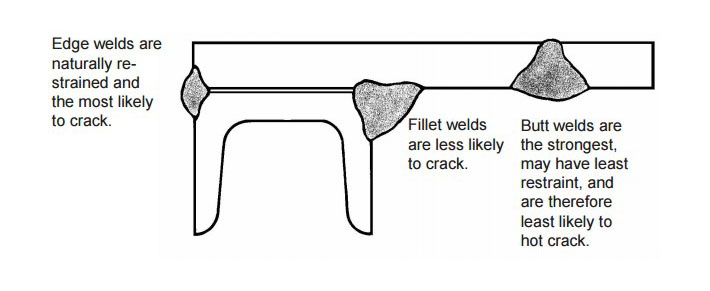

Weld metal shrinks as it freezes. To accommodate the dimensional changes associated with freezing, either the base metal or the weld must move to prevent cracking or tearing. In complex assemblies with multiple welds, each weld, when solidified functions as a stiffener, further restricting movement of subsequent welds. In such cases, the most difficult or crack susceptible weld in the assembly should be made first and the easiest and strongest welds should be made last [5]. An example is shown in Figure 13 below.

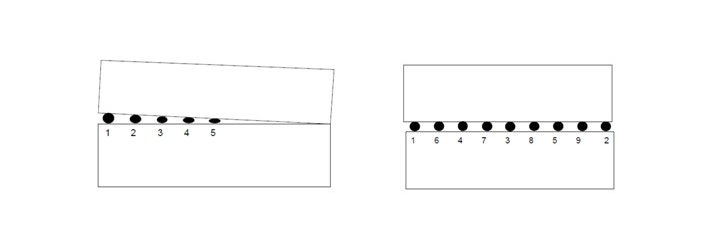

When multiple tack welds must be made, they should be sequenced along the length of the plate [5]. Tack welding from one end to the other that is made in order will result in plate edges closing up as shown in Figure 14.

Finally, multipass welds should be sequenced around the center of gravity of the joint as shown in Figure 15 below.

REFERENCES

[1] Schaefer, Anton L, Constitution Diagram for Stainless Steel Weld Metal. Metal Progress. ASM, Metals Park, OH. P 680-683. November 1949.

[2] Ogawa T. & Tsunutomi, E. Hot Cracking Susceptibility of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Welding Journal, Welding Research Supplement. P 825-935. March, 1982

[3] Li, L & Messler, R. W. The Effects of Phosphorous and Sulfur on Susceptibility to Weld Hot Cracking in Austenitic Stainless Steels. Welding Journal. Dec. 1999, Vol 78, No. 12.

[4] Kelly J. Heat Resistant Alloys. Art Bookbindery. Winnepeg, Manitoba, Canada. 2013

[5] Kelly J. RA330, Heat Resistant Alloy Fabrication. Rolled Alloys. Temperance, MI. May, 1999

[6] ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. New York, NY. 2013.