Keeping your heat treat equipment cool is as critical as it is an oxymoron.

If you have old cooling systems or are looking to purchase new ones, hear from Matt Reed, director of Sales and Technologies at Dry Coolers, as he shares purchasing considerations, maintenance, and latest technologies with Heat Treat Radio host, Doug Glenn.

Attend a digital field trip, as Matt Reed gives a tour of some equipment in action. Finally, listen in as we reflect on 100 episodes of Heat Treat Radio!

Below, you can watch the video, listen to the podcast by clicking on the audio play button, or read an edited transcript.

HTT · Heat Treat Radio #100 Cooling Off the Heat (Treat)!

The following transcript has been edited for your reading enjoyment.

Doug Glenn: Well, welcome everyone. We’re back to another episode of Heat Treat Radio. This is going to be a “cool” episode — pardon the pun! We’re going to be talking about furnace cooling systems.

When everybody thinks of furnaces, they think of heat. Probably one of the even more important things is keeping the equipment cool, as well as potentially cooling parts. That’s not so much what we’ll talk about today (part cooling), but it’s keeping equipment cool.

With us today is a cooling expert out of the North American heat treat market, Matt Reed from Dry Coolers, Inc.

Matt, first off, welcome to Heat Treat Radio.

Matt Reed: Thank you for the opportunity.

Doug Glenn: I’m really looking forward to talking with you!

I want to cover some basics, just to give our listeners a sense of where we’re going. Let me just run down through what I’m hoping that we’ll cover today: First, we’re going to talk just a little bit about you, Matt, and your company so people know who you are and how long you’ve been in the industry.

We’re going to do a very high level look at: What are cooling systems and why do we need them? It’s a very fundamental thing, but there may be some people that need to know that information.

Then, we’re going to talk about: If we need to purchase a cooling system, what are the questions we should be asking?

Next, the ever pervasive and always a thorn in our flesh: maintenance issues. These things are not maintenance-free. Briefly, what are some of the signs that maintenance needs to be done, etc.?

Finally, if we have time: we will explore some of the newer developments in cooling systems.

Meet Matt Reed (02:12)

Director of Sales and Technology

Dry Coolers

Source: Dry Coolers

Doug Glenn: Matt, again, welcome. Could you give our listeners a sense of who you are, how long you’ve been in the industry, and why you’re qualified to talk about cooling systems?

Matt Reed: Thank you, Doug. I have been at Dry Coolers for 28 years, and when you invited me to speak about this, I really had to think about it. It’s been 28 years! By default, I have so much experience that I never knew that I had!

Doug Glenn: Exactly. It’s amazing how quickly it goes.

Matt Reed: Eight years before coming to Dry Coolers, I was at another corporation. But I’ve been in heat transfer and design and thermodynamics and dealing with that side of the engineering forever. I love it. I love working with the customers.

Doug Glenn: What is your role at Dry Coolers, right now?

Matt Reed: I am the director of Sales and Technology which is a title. Really, I’m overseeing a lot of the engineering, the design. The best part of my job is talking to customers and sorting through what works for them, how we can solve their problems.

I thoroughly enjoy it. And Brian and Margy Russell, the owners of Dry Coolers, allow me to do that.

The Basics of Dry Cooling Systems (03:37)

Doug Glenn: Let’s talk just a bit, on a very elemental level, cooling systems. What are they, and why do we need them?

Matt Reed: Right. When you started this interview, you said, “Cooling, you know, it’s cool, or whatever.” It’s funny because Dry Coolers has a logo that we love, “Dry Coolers. Keeping it cool for 30 years.”

Furnaces are our core market as well as our first love. Brian saw an opportunity, saw a problem in the industry and said, “Hey, I can solve this.”

Vacuum furnaces, around the 1960s and 1970s, when they were being developed, focused on heat treating materials. Cooling is required because you’ve got these inner walled jackets in the furnace, jackets in the heads, you’ve got diffusion pumps, mechanical pumps — all these ancillary pieces of equipment that require cooling.

Originally, you could use city water and flow city water right through the furnace. Customers soon find out that that’s a lot of water consumption, so the next step was to look at an evaporative cooling tower. You start recirculating evaporative cooling tower water directly through the furnaces.

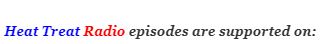

Source: Dry Coolers

For those of you that don’t know what an evaporative cooling tower is — not to get into too much of the detail here — but cooling is done by the process of evaporation. Water circulates through this tower on a roof or outside, and a small portion of that water is evaporated to produce cooling.

Let’s say you’re flowing 100 gallons a minute through a furnace. 100 gallons a minute goes through that cooling tower, and one gallon a minute is evaporated to reject heat. Now you’ve got 99 gallons a minute coming back. Now you’ve got to make up 1 gallon of water from the city water. You keep recirculating. As water evaporates, it’s just like boiling a pot on a stove — you keep boiling that pot, filling it back up and you’re going to end up with calcium and you’re going to have scaling on the inside. This is what’s happened to furnaces. It runs great for a couple of years, and then you start getting hotspots.

A lot of the old furnaces that are out there have had a rough early history because of open tower water. You had to be really diligent with your water treatment, bleeding water off from the system, adding water treatment chemicals to keep the jackets clean, and things like this. Brian saw that as an opportunity in 1985 and said, “Hey, let’s close it up. Let’s take these open water systems and recirculate them in a closed loop to protect these furnaces and stop all the scaling, all the buildup, and all this kind of stuff.

Our primary job has been trying to guide customers into what would be an appropriate closed-loop system for them whether for old furnaces or new furnaces.

Doug Glenn: Let me ask you this question: What parts, primarily, on the furnace, are we worried about cooling? I know in a vacuum furnace, we’re talking about essentially the entire shell, assuming it’s a cold-wall furnace, meaning it’s being cooled. What other things are typically cooled?

Matt Reed: They are all very important, but the shell is a big user. If you were to put 100 gallons a minute into a furnace, a large portion of that water is going to circulate through the jacket. The furnace has an inner wall and an outer wall; it’s a big annulus. Imagine you’ve got two cylinders inside of each other. That annulus is full of water, and it constantly circulates.

The other pieces of that furnace could be a diffusion pump. The diffusion pump is especially sensitive. It likes to run cool; it has small passages. If there are any flow issues or particles or debris in the system, boy, that’s one of the first places customers have trouble with plugging. Feedthroughs, mechanical pumps — these are all other ancillary.

Another big user is the quench coil or the fan. In a vacuum furnace, you’ve got a fan mounted on the back or alongside the furnace, and there is a heat exchanger inside the furnace that allows that furnace to quick-cool. We specialize in looking at the size load in a furnace and the period of time the load needs to be cooled in order to create the material property. We can guide the customer in selecting a system that would work.

Source: Dry Coolers

Doug Glenn: Right. We’re talking about high pressure gas quenching there.

Matt Reed: Yes.

Doug Glenn: I’m assuming you guys do more than vacuum furnaces. I know in a lot of atmosphere furnaces, let’s say, or air furnaces, there are potential cooling opportunities: door seals, fans, cooling jackets for continuous furnaces, etc.

Questions To Ask When Considering a Cooling System (09:33)

Doug Glenn: I’m sure you’ve got a lot of people calling you and asking you for systems. Let’s just talk about some basics. What are some of the questions that you need answered from a customer who would call in and say, “Listen, I need a cooling system” or “I think I need a cooling system.”? What do you need to know about the system in order to size the thing, or what type, even, to purchase?

Matt Reed: Flow is the first thing that we need to know. Through the furnace supplier or some other means there would be some information on what that flow requirement is, and we have a lot of that information here at Dry Coolers.

We also look at location. Somebody in Tulsa will need a different cooling system than somebody in Vermont. We know that in certain parts of the U.S., (LA, for instance), there might be water requirements. The cooling requirements in one location are very much different from another.

Some environmental regulations restrict water usage. You can’t discharge water; you can’t have a cooling tower because you’re going to have to haul your water away if you have to discharge anything. We look at the options. Very often, we go with a dry cooler.

That’s our namesake which, I really haven’t talked about. “Dry cooling” is essentially our version of an air-cooled heat exchanger with fans and a radiator that exchange heat directly with the ambient air. There’s no water usage; we fill it with glycol for freeze protection. Our happiest customers use this kind of a product because it just protects their furnace forever.

Doug Glenn: Let’s talk about Dry Coolers. What is the namesake? Why do we call it that?

Source: Unsplash/dborisoff

Matt Reed: It’s funny because Dry Coolers is a cactus, right? If you’ve ever seen Dry Cooler’s logos at the shows or anything, we’ve got this cactus. Brian can tell this story, but there was a period of time he lived down in Arizona and realized that the saguaro cactus was a perfect brand label for Dry Coolers. Our office is not in Arizona, it’s north of Detroit, but it is a cactus logo!

I want to say half of our business, or more, in terms of heat treating, is cooling using air-cooled heat exchangers directly cooling the furnaces using glycol water.

Imagine your car radiator filled with glycol. You just don’t have to worry about the interior of that engine anymore because it’s cooled. That is what we’re doing with vacuum furnaces.

Now, we have to be careful about temperatures. If you’re in southern Texas (or it could be Alaska, these days), temperatures get extremely high. Your water temperature, your glycol temperature, is going to go up. We need to address sensitive parts on the furnace — the diffusion pump or feedthroughs or whatever — and make sure the solution that we have for this furnace is going to be appropriate.

We are very pleased with the development of our air coolers.

Maintenance Issues and Solutions (13:18)

Doug Glenn: Let’s talk a little bit about maintenance of these systems because that is always a sticking point. What are the signs that your system is probably going to be needing some sort of maintenance?

Matt Reed: I want to talk about two different types of cooling systems. These are the main types of systems that we build. One is a closed-loop evaporative system where we’ve got the open tower which originally everybody used, but now we’ve put a plate heat exchanger in between. Now we’ve got one loop that’s for the furnace that is closed, and then we’ve got another loop that’s outside for the cooling tower water. That’s one.

The other system I want to talk about is our air-cooled system, but let’s do the ugly one first. The ugly one is the evaporative system. The first signs of issues are hotspots on a furnace. An operator knows: My water temperature is getting high. Feel the bottom of your furnace, feel the upper side of the jackets. If you’re starting to get heat down below, that means you’re getting sediment built up in that furnace. This is a very early sign of water troubles in a lot of vacuum furnaces. In older furnaces, you’ll see cutouts in the jackets where it has been cut out, so they can get in there and rod it out, clean it out, and then weld it back together.

For an evaporative tower system, with a closed loop, you’re generally well protected on the furnace side. Essentially, you have a clean loop side for the furnace that circulates water, and you have treated water in that side. For the most part, once it’s treated and started and running — it’s good. There is very little maintenance needed on that side of the furnace. The furnace is protected.

The cooling tower, however, is exposed to the outside air. It’s always scouring the air for any dust/debris, so the plate heat exchanger gets clogged up. You start losing temperature. It could be every year, every few years, but that heat exchanger must be cleaned. A customer calls because they’re not getting enough cooling; they’re getting too warm. More than likely, the plate heat exchanger is losing flow and needs to be cleaned.

Source: Heat Treat Today

Now, with the other side of the cooling tower, 1% of the water usage (as a rule of thumb) is evaporated in the process of evaporation. You’re always making up water. To keep that water in balance — without going into too much detail on water treatment — what happens is you have to bleed water off of that loop and then make up water in order to keep the solid’s concentrations at a level that they don’t plate out on your heat exchangers.

This was always a balancing act with the furnaces. You have a water treatment supplier that you really need to monitor this stuff. The problem here, that we found, is that maintenance crews are becoming less and less available, experienced, or knowledgeable. You’ve got a lot of attrition and then, all of a sudden, people see, “How come we’re bleeding water off this? This is just wasting money, over here, just shut that valve!” and think everything is fine.

Imagine you’re evaporating one gallon out of every hundred gallons a minute. After an hour, you’ve just evaporated 60 gallons. It really adds up. Now you look at it and say, “Oh my gosh, I’ve evaporated the entire volume of water in that cooling tower, twice a day, in order to keep up with the heat cooling requirement.” Do you know what I’m saying? Boy, you really must be on it.

In a matter of a few days of turning off that valve, you will start scaling up. You’re going to start seeing crud on the cooling tower and, unfortunately, that all accumulates in the hotspots in the system. Your plate heat exchangers will get fouled up — that’s where most of the minerals will drop out is on hot surfaces, warmer surfaces. The worst case would be if you’re circulating this water directly through a furnace, those hotspots are on the jackets, and that’s why we see that.

Cooling towers are kind of necessary for large water systems. Our internal guide is if you’ve got 300–500 gallons a minute of cooling required or above, you probably need a cooling tower just because of the amount of cooling that’s required. Anything below that, you really should be looking at air-cooled. It’s usually more cost effective, has a smaller footprint, it’s excellent for winter use and summer use, it’s just the way to go.

As far as maintenance with an air-cooled system, there is only one thing you must do — clean the fins.

Doug Glenn: Because of things that may be coming from the air that may be clogging it up?

Source: Unsplash/nionila

Matt Reed: Yes. It could be cottonwood fluff or bags or whatever is in the area that wants to get sucked underneath it. We need to either add filters, or we need to periodically clean those air coolers.

With an air-cooled system, usually the comment is, “I’m getting hot.” That usually means the air cooler needs to be cleaned.

Doug Glenn: Is the closed-loop portion of the air-cooled systems glycol?

Matt Reed: Yes.

Doug Glenn: So, glycol is in the furnace, running around cooling the furnace, and comes out and goes through the inside of the air fin where the air is being pulled in or pushed over (whichever way the air is going) it cools the glycol, and then back. I know with water systems — especially open loop, but probably even with closed loop water systems, if there is such a thing — you’ve got to monitor the water. With glycol, are there any concerns? I mean, how long does the glycol last, or is it “ad infinitum”?

Matt Reed: You know, how often do you check the coolant in your car?

Doug Glenn: Not very often.

Matt Reed: I would like to say, “Oh, yes, you need to regularly check this,” but you kind of don’t! The glycol, now that you’ve purchased, will have inhibitors in it. You can, periodically, take a sample and have it checked to make sure that it still has the proper amount of inhibitors. Essentially, if you had to add more inhibitor, it’s a matter of adding more of this chemical to the existing glycol. You don’t have to pull the glycol all out, right? It’s a pretty minor thing.

Let’s say a company gets sold, or a furnace gets sold. The furnace shows up at a new location, and it is pristine. That was a glycol system. There was glycol in that furnace. You look in there and say, “Oh my gosh, this is clean,” like the day it was first bought. That’s the beauty of the air-cooled system.

The other thing is, air coolers are often put on roofs, and they’re kind of forgotten. A lot of times it’s the last thing to be maintained, and that’s okay because they really are simple devices. The fact that they get forgotten about sometimes suggests that they don’t need a lot of attention. Our happiest customers — honestly, and I’m not selling you the business here — have air-cooled systems. We like it for that reason too. It’s very robust.

Doug Glenn: If you’re needing 300–500 gallons per minute or over that, you’re going to tend towards an evaporative system. When we’re talking about the air-cooled stuff, completely closed loop — as far as the liquid goes — that’s going to be less than 500 gallons per minute, less than 300 gallons per minute?

Matt Reed: To be clear, we have customers that have 1000 GPM systems, and they are air cooled. Those customers have 10 air coolers in a bank. We have customers that say, “Oh, no no, they are strictly air cooled. We’ll take those 10 air coolers because they are zero maintenance, and they’re very energy efficient.”

One of the big motivating factors is electricity. In some locations in the United States, it is very expensive. All of our air coolers have variable speed fans. In the wintertime or when it’s 40 degrees outside, you might have 24 fans, but only four of them are running. They ramp up and down to regulate temperature. You’re directly cooling that glycol with the ambient air, so when it’s cool outside, boy, you’re just as energy efficient as you can be. It’s terrific!

On the flip side, if you have an evaporative cooling tower, in the winter, you’re always running water outside. It’s splashing down, and you get a little bit of mist coming out that creates icicles. Now you’re getting either rooftops or parking lots with ice on them — this is not uncommon. The cooling tower that you use needs to have very low drift and things. We deal with them.

Doug Glenn: There are more considerations.

Matt Reed: Yes. If you’re 300 GPM or less, even if you’re in Mississippi — some place hot or muggy — we’re going to look at it. We’re seeing more and more customers, further south, using our air-cooled heat exchangers, in these applications, just to get away from water usage.

Doug Glenn: For manufacturers who are doing their own in-house heat treat, who have maybe a variety of different furnaces, do you tend to find that they are using one system per furnace, or are we typically combining systems and have a building-wide cooling system? What are the considerations there, Matt?

Matt Reed: Usually it doesn’t start out that way. A customer buys one furnace and then another one or two more, and so you end up with — oh, we’ve got one here, we’ve got one here and we’ve got one here. We have had customers with 10 furnaces and 10 water systems, and it takes up so much floor space. There is some regret on the part of the customers for having to maintain 10 different cooling systems.

Yes, in an ideal world, we would definitely be looking at a central system where you would have your built-in redundancy, and you would only use as many cooling systems or fans as needed.

Whether a furnace is running or not, oftentimes the water system is let run. An operator will just let it run. Even if it’s out of cycle, while it might not be fully cooled, the water is just left running. All of these systems could be running, but they are not producing. That’s really wasting energy. A central system allows you to take the entire plant load up and down more efficiently. Ideally, we would want to look at central systems.

Doug Glenn: And you can control the output of that central system just the same as you can for an individual system, always keeping the outlet glycol at a certain temperature, I assume?

Matt Reed: Yes. In fact, I think, even a little bit better. If you’ve got 10 furnaces, operators can’t load all 10 furnaces at the same time, so they’re never in cycle at the same time. You get this diversity. You might have one furnace going into quench, for example. A large system really kind of evens that all out; it runs pretty efficiently.

Latest Developments in Cooling Systems (26:48)

Doug Glenn: Before we wrap up, some questions about some of the latest developments. We have talked about some considerations when we want to buy new equipment. We have talked about some of the maintenance and some basic maintenance things. What are you seeing as far as new developments in this area? Are there new products, processes, materials that are being used to design these systems, or how they’re used?

Matt Reed: We’re seeing more and more air-cooled systems being installed. When I started 28 years ago, a lot of them were evaporative cooling towers and a little bit of air coolers. It was a little bit of both and a little bit more cut and dry. Now we are seeing more and more customers requiring variable speed drives per pump. Now, our default is variable speed drives on all fans. If you buy an air cooler from us, it will have drives that will just ramp up and down to match your load; it’s really efficient.

We’re seeing a lot more requests for adiabatic air cooling, where you’re using an air cooler but you’re providing a little bit of a mist assist on a hot day to knock the edge off of that. When there is a 100-degree day, turn the misting on. We are precooling the air before it goes through the air cooler.

Doug Glenn: I’m assuming you can only do that in some geographies because that doesn’t work so well wherever it’s humid.

Matt Reed: That’s right.

Those are the big areas. A lot of facilities have less and less maintenance people. There is a lot of attrition, and we’re losing a lot of experience, unfortunately, in maintaining these facilities.

In the past five years, we’ve been on this development kick on our ABI series air coolers that led to the variable speed fans, leaning more and more towards maintenance. The main area where we see our air coolers needing assistance is those climates/locations where you’ve got cottonwoods. You need filters for the air coolers, and how do you clean them easily? We’ve made some developments on our air cooler that allow us to slide our fan out of the way. A wand gets down in there to clean out, to spray in some foam detergent to clean out the units. There are some features that we’re adding to these units to make it easier to maintain. They’re pretty easy, really.

Doug Glenn: Has the focus on sustainability and green technologies affected you guys, at all? I’m thinking, primarily, are we seeing more companies moving to vacuum furnaces and therefore that affects the number of units you guys are putting out? Are you seeing anything in the sustainability area that is impacting your business?

Matt Reed: I think Dry Coolers has been perfectly positioned for that. I think we’ve been environmentally friendly and focused on the environment right out of the gate. The whole closed loop idea with air coolers falls right in line with minimal emissions, minimum discharge to your water, to your environment, storm drains, etc. I think that we’re in a good position there.

From a trend standpoint, this is something that Brian and I have discussed many times. Brian is convinced, and it’s true, that people really want to move away from cooling towers. The choice is going to be: Do you get an air cooler or a chiller? It’s all closed loop; there is no evaporation, there is no water treatment and there is no discharge and all that. These two pieces — a refrigerant chiller and an air cooler — are the two main selections. We’re seeing a lot more chillers being purchased, at the expense of electricity, because chillers consume a lot more electricity. Air coolers are much more favorable from an energy usage standpoint and therefore for the environment.

We’re seeing combinations where we use a chiller in the summer during the heat, but we’ll use an air cooler the rest of the year. We call it a hybrid system where a customer really must have 85 degrees, but they only want to use a closed loop air cooled system with glycol. Okay, air cooler 90% of the air and here’s the chiller, for a small portion of the year, to take the edge off the heat — zero water discharge.

We’re able to be creative like that and work with the customer’s footprint, their location, etc.

Doug Glenn: Are you seeing any, let’s say, closed-loop monitoring of equipment? For example, on your fans — fan vibration on your air cooling systems — are you seeing any of that going on, as far as helping with maintenance?

Matt Reed: I will tell you, we’re seeing a lot of requests for link-IO. I know that’s a very specific term, but this is where we take our instrumentation off our cooling system and we tie it into this central link or ethernet hub. There is no PLC, there is no HMI, but now we’ve got temperatures, pressures, flow, level — whatever critical measurements a customer wants — and boom, here it is. Now, they can take it directly back to their building management system.

I’m floored by how many customers want that, and they just buy it. That’s a much easier solution for us to provide than a full-blown PLC or custom PLC for every customer. Every customer is a little different — this building management system is Siemens, this one’s CompactLogix, or whatever — you’re dealing with all these different networks and things.

I’m fortunate enough to not have to get into that nitty-gritty. Dry Coolers has an awesome team. I didn’t mention it, but we’ve got 65 employees now. When I started, there were five of us. I’ve got nine engineers, I’ve got so many designers and electricians, and it’s just fun. It really is. I’ve got so many experts in all these different spots that are liking what they do — it just makes the day go by.

Doug Glenn: That’s great!

Thanks for being with us, Matt.

Matt Reed: Thanks for the opportunity. This was fun.

Supplemental "Field Trip" for Tips on Air Coolers (36:05)

Join Matt as he gives some live-action tips on how to check air coolers to ensure they are plug free and working properly.

Matt Reed: I wanted to show you our air-cooled heat exchanger. These are very helpful tips for your commercial heat treaters. If they’re walking around the unit, trying to find out if it’s clean, how it’s working, there are some easy things that they can do.

Here’s what I would like to share with your audience: If the fans are working well, that air is coming straight up and out. If it’s dirty, if the fin surface is dirty and it’s having a hard time moving air, that air is going to want to push out to the side.

This fan does not get as much of the out-blowing as you do on our legacy unit. We have a lot of customers with a different style fan. Boy, that air will really push out to the side, if your coil is dirty.

Now, it’s not easy to crawl underneath there and check your fins. And it might look like the fins are clean and your guy might have said, “Yes, it’s clean. I just cleaned the air cooler.” I’m telling you, if your air is pushing out the side like this, it’s still dirty.

Source: Dry Coolers

So, what do you do if it’s dirty? We have a bulletin that we can send to you, but here is the short version of it: For this air cooler, you would unbolt these bolts on this fan and you would prop it up with a 4x4 or something so that you can get underneath it. You can blow out with air or a gentle spray of water or you can use a there are different refrigerant or evaporator foaming solutions you can spray with a wand in there and the foam will push out any dust and debris, cottonwoods or whatever has been sucked into it. It makes a huge difference.

You want the air cooler to run as close to ambient as you can. If it’s dirty, you’re wasting energy. It’s way better for your process to run as cool as possible.

Let’s check one other thing: That’s the air cooler. Compared to a cooling tower, that’s like nothing. There is very little maintenance. These are usually sitting on a roof and you kind of forget that they’re up there and running. But they do get dirty and they have to be checked.

Here’s the other thing: These are the inlets. Now, this is a new unit, and of course this would all be hooked up to your process. So, your inlet is on the top going in, and your outlet is on the bottom. You should be able to put your hands on here and feel a difference. It should be warm coming in and cool coming out. The thing you want to look at is if you’re 60 degrees outside, you should be able to make 70 degrees coming out of this process. If it’s really warm, that’s another indicator that you’ve got a dirty heat exchanger coil.

We usually size these or design these so that you can get within five to 10 degrees of whatever the ambient is. Again, it’s 90 degrees outside, you should be getting 95 – 100 degrees feeding your equipment.

Heat Treat Radio's 100th Episode! (38:47)

Source: Heat Treat Today

Celebrate this 100th episode with us and listen to Doug reflect on his past seven years of Heat Treat Radio leadership….

About the expert:

Matt Reed (P.E.), director of sales and technology at Dry Coolers, Inc., graduated Michigan Tech in 1987 where he met his wife, Carol. They moved to Ohio to work for B&W/McDermott for 8 years. He started working with Brian Russell at Dry Coolers, Inc. in 1995 building closed-loop cooling systems for furnaces. Back then, the company had about 5 employees. Today they have 65 employees and build cooling equipment for a wide range of industries. Matt thoroughly enjoys working with customers and colleagues in the heat treat industry and is happy to share his experience with our readers and listeners.

Contact Matt at matt.reed@drycoolers.com

To find other Heat Treat Radio episodes, go to www.heattreattoday.com/radio.